Roopa Chauhan

April 12, 2024

Powerful emotional and musical undercurrents will draw audiences into this 21st century American opera by composer Missy Mazzoli and librettist Royce Vavrek. The production originated with director Tom Morris in Edinburgh in 2019. The 2024 version is an international co-production of Opera Ventures, Scottish Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Adelaide Festival, and Théatre National de l’Opéra Comique. Diana Wyenn directs this revival, which opened on Saturday, April 6th at the Detroit Opera House. It continues this weekend with two performances on Friday, April 12th at 7:30 pm and on Sunday, April 14th at 2:30 pm. For more information, please visit: https://detroitopera.org/season-schedule/breaking-the-waves/

A Story Made for the Operatic Stage

Absolutes collide in Breaking the Waves, an opera inspired by Lars von Trier’s 1996 provocative film of the same name. Both the film and opera ask difficult questions about the nature of love, faith, loyalty, and sexuality. While the story refuses to provide easy answers, Missy Mazzoli’s score delivers on its promise to take audiences on a musical journey unparalleled in its beauty and scope.

If there ever was a character suited to the operatic form, it is that of Breaking the Waves’ embattled main protagonist, Bess McNeill. Her story is set in a remote part of Scotland during the 1970s. She is fated to suffer greatly in an environment that is physically and spiritually austere. But the opera begins on a hopeful note with Bess falling in love with Jan, an offshore oil rigger. The elders in her strict Calvinist community reluctantly grant her permission to marry the outsider.

The newlyweds enjoy a brief period of matrimonial bliss, and sexual awakening for Bess, before Jan must leave for the rig. The four-week separation proves unbearable for Bess. Both her fragility and strength are on full display as she pleads with God for Jan’s return in a series of personal conversations where God speaks through Bess to tell her what she should do.

Jan does return quickly, but only to be hospitalized after a near-fatal accident on the rig leaves him paralyzed. Distraught, Bess blames herself for Jan’s injuries because she begged God to send him home to her. Convinced God is punishing her, Bess’ Calvinist faith and love for her husband are pitted against each other.

Knowing that his injuries make physical intimacy impossible, Jan assigns Bess “a task”. He demands that she have sex with other men and then share the details of her exploits with him. She protests, but he insists, so she agrees albeit reluctantly. When she realizes that carrying out the tasks helps Jan get better, Bess pursues them with renewed fervor, but negative consequences for her own safety and sense of belonging: she is excommunicated from the church.

A Story That Asks Big Questions

Much like Cio-Cio San in Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, Bess struggles to find a path forward. Her agency is limited by structural constraints inherent to a patriarchal society. She hears the voice of God, but her own is drowned out by everyone telling her what to do: the church elders, her mother, her sister-in-law, Dodo, her doctor, and Jan. They all agree that she should be a “good girl”, but they do not agree on what “good” means and they do not refer to her as a woman or an adult; she is constantly infantilized.

She must obey her husband, but at what cost? She must follow the teachings of the Church, but what if they contradict her husband’s demands? During the Opera Talk preceding the show, Mazzoli described Bess as “a woman in an impossible situation” who is left to find her own morality and forge her own path. But, in this context, how much agency can Bess have? She is stuck between a rock and a hard place, torn between her moral obligations to the church and her love for her husband.

Are Jan’s tasks or demands motivated by love or is his judgement clouded by the head injury, as Dodo suggests? Should we really do anything for love? If the only choice available sets one on the path of no return, is it really a choice? What happens when extreme masculinity (Jan and the church elders) clashes with extreme femininity (Bess)? Breaking the Waves leaves us with these important questions to ponder long after the final notes are played.

Music and Set in Service of Story

The Detroit Opera Orchestra led by the brilliant Stephanie Childress, who is making her Detroit Opera conducting debut, played Mazzoli’s complex score with subtlety and finesse. The music acts as a unifying force, resolving and heightening tension all while echoing conscious and subconscious emotions. In contrast the arias are searching and melodic, carving out a path forward for each character.

That Breaking the Waves was written in English made the singers’ vocal prowess more apparent; the language was less of a barrier, which perhaps made it easier to notice the full range of their vocal expressivity. Gabrielle Barkidjija played Dodo, Bess’ supportive sister-in-law; her warm mezzo-soprano voice reassuringly wraps Kiera Duffy’s delicate (but no less powerful!), bell-like soprano voice in a hug. Elizabeth van Os’ rich, dark soprano voice embodies Bess’ stern mother expressing a range of emotions from anger to fear and ultimately coldness, but never indifference to her daughter’s plight. As Bess’ doctor, David Portillo’s versatile tenor voice conveys the kind-but-firm disposition required of a mild -mannered country doctor. Baritone Benjamin Taylor plays Jan, Bess’ husband; his gorgeous deep baritone gives the oil rig worker an aura of cool nonchalance.

Detroit Opera Assistant Conductor and Chorus Master Suzanne Mallare Acton’s skill could be heard behind every note the men’s chorus sang. Their versatility is impressive as they transform from ominous church elders to boisterous townsfolk, managing to create an oppressive, ominous atmosphere as they tower over the only three women in the production.

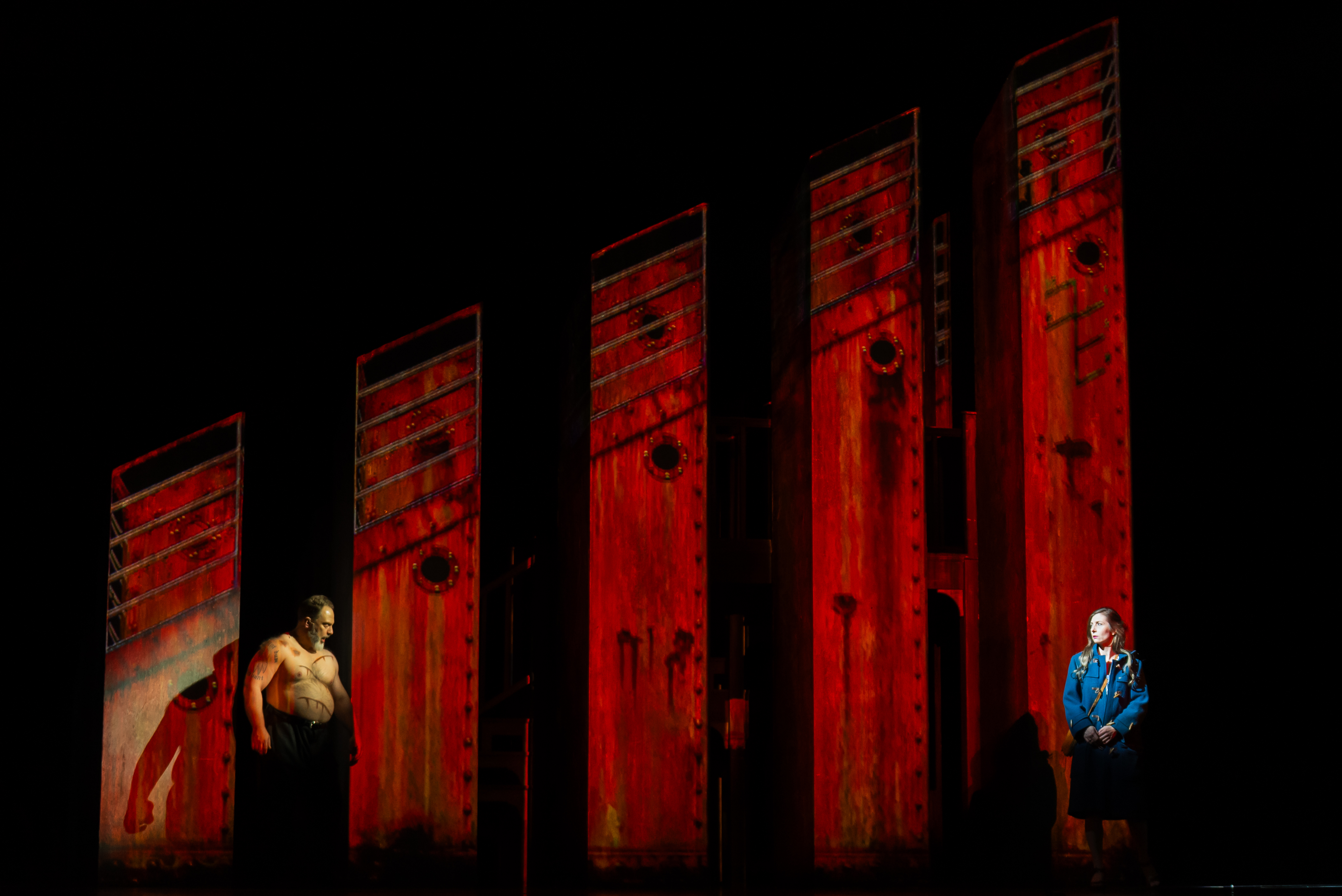

The multi-functional, economical set design matched the powerful performances. The centerpiece is a large rock-like formation, mirroring the jagged edges of the Isle of Skye in Scotland, where the opera is set. The rectangular pillars are also screens onto which images of waves crashing into rocks or the rusty side of a ship can be projected. Like the music, the projected images are an extension of what is taking place on the stage emotionally. When the structure turns, it transforms into what the scene requires: the inside of a church, a ship or a doctor’s office.

Breaking the Waves may not be a conventional opera, but it is opera at its best: forward-thinking, bold, and expansive. While it may not afford Bess the agency she deserves, it does raise compelling questions about a woman’s place in a patriarchal society that resonate today. In the production’s program book, Detroit Opera’s Artistic Director Yuval Sharon states that with Breaking the Waves.

“Mazzoli has asked opera audiences to journey into a territory we’re never asked to go. The piece requires our maturity in thinking about sex. It asks us to consider why the most natural and beautiful thing we humans do has been weaponized for so long by men seeking to place women in socially disadvantageous circumstances. When our culture sharply separates morality and sex, we internalize that conflict in devastating ways”.

This astute observation is perhaps what is at stake in the opera’s violent gender-based power dynamics. Recognizing that the two forces of morality and sex are in conflict could be a first step towards redressing the gender imbalance and shaking loose patriarchal structures.