Leonie Hagen

April 26, 2021

“To truly know a city, we must know who believes in it, who invests in it, who has a stake in its future.” 1

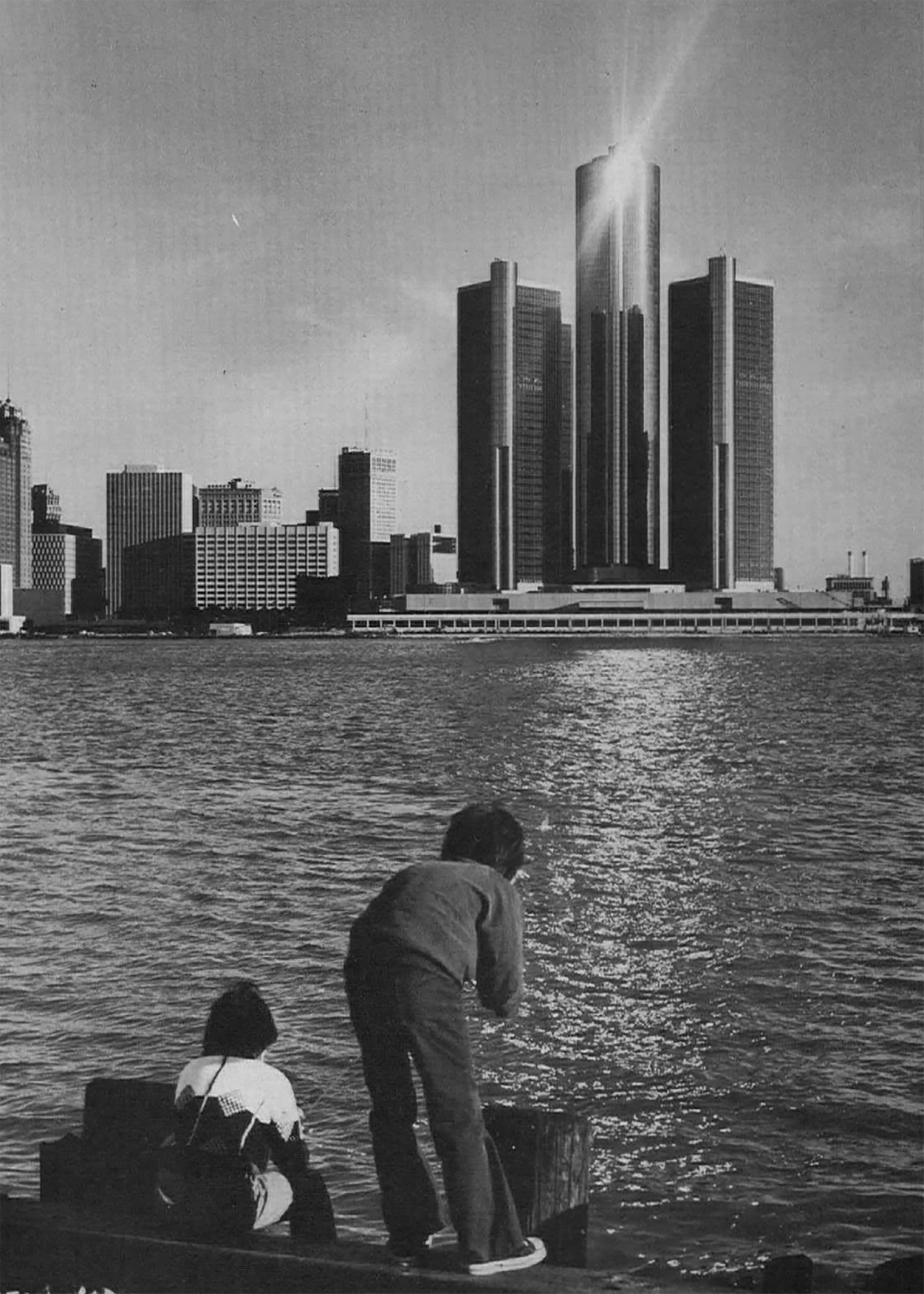

Anyone who has ever been to Detroit can’t help but notice the eye-catching Renaissance Center. As the tallest building in all of Michigan this massive complex clearly dominates Detroit’s skyline. It’s both intriguing and repellent; intriguing by its mere size and its futuristic look, repellent by its unapproachable and defensive appearance. The building’s name tells much of its story. In the 1970s, Detroit had begun to suffer from the effects of “white flight” and neglect; end-products of a failing (mono-)economy, racial inequality and civil unrest. Detroit, still a city of approximately 1.5 million people at the time, was heavily scarred by the 1967 Detroit Uprising and the city’s leaders were looking for ways to bring their city back. As a consequence of the racial polarization and rising crime rate, money began to flow out of the city into the suburbs. Businesses relocated to suburban malls, professional sports teams moved out of the city. 2

The idea of branding a ‘Renaissance’ was conceived by Henry Ford II, CEO of the Ford Motor Company, in 1970; together with other powerful Detroit businessmen as well as then-mayor Roman Gribbs and then-governor of Michigan George Romney, he founded ‘Detroit Renaissance, Inc.’, a private non-profit development organization to stimulate building activity within the city and revitalize Detroit’s economy. The concept was then sold to the city and Gribbs touted the project as ‘a complete rebuilding from bridge to bridge’ 3, referring to the area in-between the Ambassador bridge to Windsor, Canada and the MacArthur bridge to Belle Isle Park. The heart of the anticipated Renaissance would be the Renaissance Center; primarily financed by the Ford Motor Company, 52 of the leading companies in America joined forces to make this project possible. 4 Henry Ford II branded it as an investment and a public statement of commitment to Detroit: “This development is being built by the people of Detroit for the people of Detroit. And I’m convinced as many other people are as well, that this will be a catalyst for the Renaissance of Detroit. And the Renaissance has already started, but this will be a great step forward.” 5, as he stated at the opening ceremony of the RenCen in 1973. The project would become the world’s largest private development with a building cost of about $350 Million. 6

To facilitate this massive undertaking, Henry Ford II approached the then already famous Atlanta-based architect John C. Portman Jr. who was known for his large-scale projects across the United States and most importantly his atrium hotels. The Renaissance Center is merely one of dozens of projects of that size by Portman, who significantly defined many of America’s most prominent downtowns. The 32.5 acre site just off the Detroit river was a difficult one as Portman remembered in an interview about the RenCen: “The site for Renaissance Center was isolated from the city (...) It is separated from the city by a 13-lane freeway on one side, and a tunnel from Windsor, Canada, on the second side. A series of railroad tracks isolates it on the third side, and finally, on the fourth side, is the river.” 7 Portman and his team accepted the commission and developed a master plan that envisioned a very much inward-oriented complex, which seems like a natural choice for a site as isolated and island-like as the one selected on the outskirts of Downtown Detroit. “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong”, as Henry L. Mecken wisely stated. 8

The 7-tower complex was constructed in two phases from 1973 through to 1981. Originally three phases were planned but a good chunk of the second phase as well as all of phase three were postponed indefinitely: a quite substantial amount of low-rise housing along the river, as well as bridges that were supposed to connect the complex better with the existing city, were never realized. 9 Those missing bits, foremost the housing part, would probably have changed the perception of the complex to a substantial degree. It would have helped to bring life to the ensemble outside of working hours and intermittent conventions.

The centerpiece of the development is a cylindrical 73-story, 727 ft (221.5m) luxury hotel tower surrounded by four octagon-shaped 39-story office towers with a height of 552 ft (159m) each. All of them are lifted up on a 14 acre, 5 story concrete podium and those towers are again accompanied by smaller cylinders which house the lifts and offer spectacular views while traveling upwards. The main tower houses 1,400 hotel rooms, a major conference center including a ‘Renaissance Ballroom’ for events, as well as an upscale, 3-story restaurant at its top. “The Detroit Plaza will house 11 restaurants, but none quite like [‘The Summit’], which crowns the hotel 700 feet above the city. (...) Two of [The Summit’s] three levels revolve 360 degrees, you sit in your chair and watch the city 70 stories below; turning, changing before your eyes. Each minute a new, fresh perspective of Detroit. A city reborn.” 10 The four office towers provide 2.2 million square feet of office space. The base they’re all rising from contains a massive atrium, Portman’s trademark, which is largely devoted to a mall including stores, restaurants, and a movie theatre. On the lowest level, an artificial one-acre indoor lake with a circular island-lounge was to be found which served as an integrated lobby for both the hotel and the offices. The rest of the atrium was dedicated to the convention space which was connected to the hotel. 11

As James Burke, a then-famous scientist with a documentary series on BBC highlights parallels between the architecture of the Renaissance Center and the industrialization and automatisation of the time: “This is many people’s vision of the world of the future. In many ways it represents the world we already live in; a massive, complex end product of everything technology can do. A structure that depends for its existence on the production line and the world the production line has generated. That production line has done many things to us by giving everybody everything [that] everybody else has: the same houses, the same daily routine of work, the same cars to go to that work, the same dependence on the clock. Cities criss-crossed by roads that fill up twice a day, the same view of the world from the same TV set, the same hopes, dreams, ambitions. (...)” 12 With this statement he also ties the project back to being an inherent product of our capitalistic reality.

“An architectural extravaganza is hoped to return vitality to the doyenne of decayed downtowns—Detroit. But can architect John Portman draw crowds and keep them there? Will the transplant live but the body die?” 13

Born in South Carolina, Portman graduated from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1950 and founded his own firm in Atlanta in 1953. It was on a study trip to Brasilia, a notoriously planned city and stamped out of the ground in the 50s, that Portman had a change of heart regarding architecture. He felt like the architecture there was detached from the human scale and cold, he wanted to create spaces that ‘enhance life’ and ‘lift the spirit’ 14. When Portman began his career in the 1950s, there was a shift happening in modern architecture and urban design. The intention of architecture was moving away from a philosophical and idealistic viewpoint and a will to change or revolutionize the world to a rebranding act of capital. Modernist architecture found its way into the upper echelons of American corporations and became a tool to create new images for those firms.

American architects were judged for borrowing the form from modern masters, but not the substance and meaning of their creations. 15

Getting tired of waiting on clients with the same visions as his, Portman started to become a developer himself, mixing the fields of architecture and development for the first time. He spent the 60s designing and developing the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, an office, hotel, wholesale-mart and convention center complex downtown. This undertaking earned him the title “one man urban renewal program” 16 By means of his Atlanta project, Portman was promoting himself to potential future clients, seeking a new way to find a clientele that would support his vision. Portman was an advocate for downtowns, claiming that they are essential and necessary to metropolitan regions and can not be abandoned and replaced by suburbs.

Portman claims to be interested in urbanism and community, yet his views of what society wants is somewhat narrow. He projects his social perspective and that of his (white male) clients rather than dedicating himself to a more democratic process of design in order to include the general public. Therefore Portman’s architecture appears as a very top-down process, he included programs that he felt were needed and by this excluded a large number of people right from the start.

This exact contradiction made him one of the most controversial architects of modernism; some think he’s genius and ‘put a spark back’ 17 into the city, some think he had no interest in true and genuine urbanism and vacuumed the cities through the construction of his projects. As Michael Sorkin, a highly appreciated architecture critic put it: “Mr. Portman’s buildings are exciting without being interesting. Paradoxically, his buildings, which practically scream their aspirations to urbanism, are virtually without a sense of urbanism…like giant spaceships, offering close encounters with the city but not too close.” 18

Most of Portman’s architecture projects are massive in scale and some are quite similar which brought him the reputation of creating interchangeable ensembles and “architecture packages that can be dropped on any city” 19 The RenCen for example has many times been criticized for not taking advantage of its prime riverfront location but basically blocking the view of the water from most places. There was no access from the public lobby to the waterfront until a more recent renovation. Portman’s complexes are too large to grasp and per architect Rem Koolhaas “beyond a certain scale, architecture acquires the properties of Bigness. (...) with a parallel potential for the reorganization of the social world”. Portman wanted to create worlds of his own, a ‘village within a city’ that would occasionally connect to the original city where appropriate and desirable. “Together, all these breaks – with scale, with architecture as composition, with tradition, with transparency, with ethics – imply the final, most radical break: Bigness is no longer part of any urban tissue. It exists; at most it coexists. It’s subtext is fuck context.” 20

If only briefly, crowds of people visited the Renaissance Center after its opening and it became a popular destination for locals and tourists alike. Curious and intrigued by it’s mere size and appearance, people wanted to see what was going on in downtown Detroit. The center became the symbol for a rejuvenated Detroit, as tourist guidebooks and maps, television shows, and televised sporting events used the Renaissance Center to symbolize Detroit, even if those events were taking place in the suburbs. The RenCen became the motif for postcards from Detroit, it simply dominated everything coming from the city and became its flagship. Even before its completion it was highly advertised with short clips showing its building process and orbiting huge high-end models of the development, promising excitement, spectacle and glamour.

There’s no doubt that the RenCen influenced the pop culture of Detroit as well, it has appeared on album covers, on movie screens, and in video games (see fig. 11). There’s a long list of movies being filmed in and around the Renaissance Center: Action Johnson (1988), Collision Course (1989), Grosse Pointe Blank (1997), Out of Sight (1998, see fig. 4), Killshot (2008), Need for Speed (2014), just to name a few. All those movies play on the alleged dangerous reputation of Detroit and are some kind of action movie with an underlying sense of danger. It seems like including the RenCen in those screenplays on the one hand located the movies in the city of Detroit which already adds a particular vibe to it; but also adds another layer of spectacle and megalomania. Much as in reality, the building is oftentimes used as an escape from the streets of Detroit: to relax in an upscale hotel room, have a spectacular meal in a rotating restaurant, to simply get away from the constant threat of the citylife for a little while. As writer William H. Whyte summarizes the building’s appeal to the people: “But the message is clear. Afraid of Detroit? Come in and be safe.” 21

This very much goes hand in hand with Detroit’s reality at the time. The planning and construction of the RenCen started just a few years after the tragic 1967 Detroit Riot, a riot sparked by a long history of racism and race-based discrimination in housing, labor, city planning, and politics both within the city and throughout the metropolitan area. 22 Furthermore Detroit, a city with a black population of about 40% at the time was heavily misrepresented among the police force and local government. In 1967 civil disorder broke out in 128 cities across the United States, but the Detroit Riot is considered the worst of all those cases and is considered one of the worst insurrections in American history, it was seen as the nadir of the country’s urban crisis. The riot claimed 43 lives and left the city with an approximate $300M. in property damage and about 2,500 looted and damaged or destroyed businesses. 23

The wish for a Detroit Renaissance is a clear reaction to the riots of ‘67 and its subsequent developments and projects were claimed as tools to save Detroit and bring it back. Yet when putting the reaction of Detroit’s powerful leaders to the riots in the form of a fortress-like building into perspective, one can’t help but cringe. The obvious purpose of the Renaissance Center is to create a safe environment for certain social classes, members of the community who didn’t typically live within the city, social classes who didn’t need the attention at the time. This project clearly turns its back on the city and therewith on the people who still live in the city and didn’t flee to the suburbs and seems to have ignored much of what was wrong with Detroit at the time. Creating safety was the foremost drive in the design process, as architect John Portman reinforces: “Cities, and certainly Detroit, have at least the image of being unsafe places. To reverse that, we have to give people city environments where they feel safe.” 24 When considering the ongoing outcry against redlining, racial injustice and police brutality against African Americans and other minorities into perspective, the idea of the city within a city loses its futuristic and mysterious appeal and turns dark pretty quickly. The white leaders of Detroit put their heads together to find a way to keep the white folks from moving out of the city or to at least give them a reason to pay Detroit an occasional visit for shopping or dining. The elephant in the room is being ignored.

The Renaissance Center appears ‘like [a] snobby rich kid shying away from low-class neighbors’ 25, as it very much plays with the fear of white suburbanites and recognizes their mindset and their interaction with black and brown folks as acceptable or even appropriate. The building complex has been stigmatized as a “Noah’s ark for the white middle class” 26 and received strong criticism from Detroit’s working class: “[The] RenCen really doesn’t appeal to the average person in Detroit. It’s too expensive. (...) It’s an eyesore that was basically built for the mayor. It’s not going to alleviate the main problem here, which is skilled laborers who can’t get a job.” 27 Instead of being a place for the people of Detroit, the RenCen rather appears as a “fortress” for white people from the suburbs who still want a downtown experience without getting in touch with the real city and dealing with its issues. “In other words, while it attempts to be nothing if not a celebration of space - some sort of cathedral to the unique spatial biases of contemporary urban production - the inner city atrium is ultimately only a simulated world which is compromised from the outset, unable to acknowledge the far more consequential space its construction brought into being.” 28

To autopsy projects such as the Renaissance Center is complex and multi-faceted. While it might well be visually exciting, spatially intriguing and astonishing in size, it has to be regarded critically. John Portman and the initiators of the Renaissance Center had or claim to have had good intentions, but nevertheless, it is obvious that the Renaissance Center didn’t keep its promise and might have done more damage than good. At a time when the leaders of Detroit should have listened to their angry people and tried to support those in need, they decided to again invest in the white middle- and upper-class and further marginalize the already vastly excluded parts of the community. Already at the time the RenCen had a negative effect on businesses and office buildings elsewhere in the city, it vacuumed a large part of the remaining life out of the city streets.

It’s obvious that exclusive architecture cannot produce a healthy city, especially not in a city struggling through a huge social and economical crisis. Enclosed spaces are always somewhat exclusive and the Renaissance Center has shown that as much as it wants to be “public” and the end of the day it’s not. A policed space excludes certain people depending on its policy; a middle-class oriented range of shops attracts the middle class.

With Detroit undergoing another wave of protests about the same old injustices and with the city undergoing change yet again by becoming more popular for investors, one can just hope that the leaders of the city have learned their lesson from this failed naive or intentionally segregating utopia and keep in mind what damage they have done with this massive development.

While the RenCen has been transformed over the years and many of its flaws have been smoothed away, it will however remain a peripheral island, contrasting the city, rather than becoming a part of it. It was never intended to be transparent and inclusive, but instead turned its back “on the surrounding city”. 29 Now that the city of Detroit is recovering from its bankruptcy and downtown is sprawling again and people feel safer on the city’s streets, what future does the Renaissance Center hold other than being a dated and devalued landmark?

1. Transcript of: Detroit Historical Society (1976). Detroit Ren Center. Link.

2. Desiderio, F. (2009). „A catalyst for Downtown“: Detroit’s Renaissance Center. Michigan Historical Review, Vol. 35 (Spring 2009), 83–112. Link.

3. Desiderio, 96.

4. Desiderio, 94.

5. Transcript of Henry Ford II.’s speech at the ground-breaking of the RenCen: “Renaissance Center: A Look at Tomorrow”(1973). Link.

6. Meredith, R. (1996, May 17). “G.M. Buys A Landmark Of Detroit For Its Home. The New York Times. Link.

7. Riani, P. (1991). John Portman. Aia Pr.

8. Gratz, R. B. (2018, 9. Juli). Will Detroit Ever Fully Recover From John Portman’s Renaissance Center? Common Edge. Link.

9. Desiderio, 102.

10. Transcript of: Detroit Historical Society (1976). Detroit Ren Center. Link.

11. Desiderio, 97.

12. Transcript of: Burke, J. (1878). Connections: Thunder in the Skies. BBC Documentary.

13. Wright, B. N. (1978). Megaform comes to Motown. Progressive Architecture, 2 (78), 57–61. Link.

14. Transcript of an interview with the architect in: “John Portman – A Life of Building” (2011)

15. Desiderio, 91.

16. Barnett, J. (1966). “John Portman: Atlanta’s One Man Urban Renewal Program,” Architectural Record 139 (January 1966): 133-140.

17. “John Portman – A Life of Building” (2011)

18. Gratz.

19. Gratz.

20. Koolhaas, R. & Mau, B. (1997). ‘Bigness or the Problem of Large,’ S, M, L, XL. Monacelli Press.

21. Whyte, W.H. (1988). City: Rediscovering the Center. Doublepay, 207

22. Desiderio, 85.

23. McGraw, B. (2017, 20. February). A quick guide to the 1967 Detroit Riot. Detroit Journalism Cooperative. Link.

24. Williams, R.M. (1977, May 14). ‘Saving our Cities,’ Saturday Review.

25. Wright, B. N. (1978). Megaform comes to Motown. Progressive Architecture, 2, 57–61. Link.

26. Desiderio, 102.

27. Barnett, 133-140.

28. Pope, A. & Aureli, P. V. (2015). Ladders. Amsterdam University Press, 129

29. Whyte, 207.