Chris Pinter

February 27, 2023

When viewing bree gant’s Wend, currently on view at Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, I reflect on our bodies in relation to space. Interior space, space within our bodies, exterior space, space our bodies take up in the world and the infrastructural space our bodies are confined by. An undercurrent to these wafts is the concept of time. I think about time spent with our bodies, time in our bodies, time in the world, time in constructed spaces. The dewy sensation presented by scenes of Wend forms a connection between space and time like a sort of amniotic fluid.

Edited with a slow, rhythmic pace, there is a watery undulation to the tempo of gant’s sequences. A short, looping audio track of a field recording that feels distinctly like late summer. There’s a humidity to the audio the way the bird songs echo in the lush greenery of Michigan in the quiet space at the end of a hot day. Coupled with visuals representing all four seasons, the piece takes on a gestational atmosphere like that of a tide from one of our many lakes rolling in on that same summer evening.

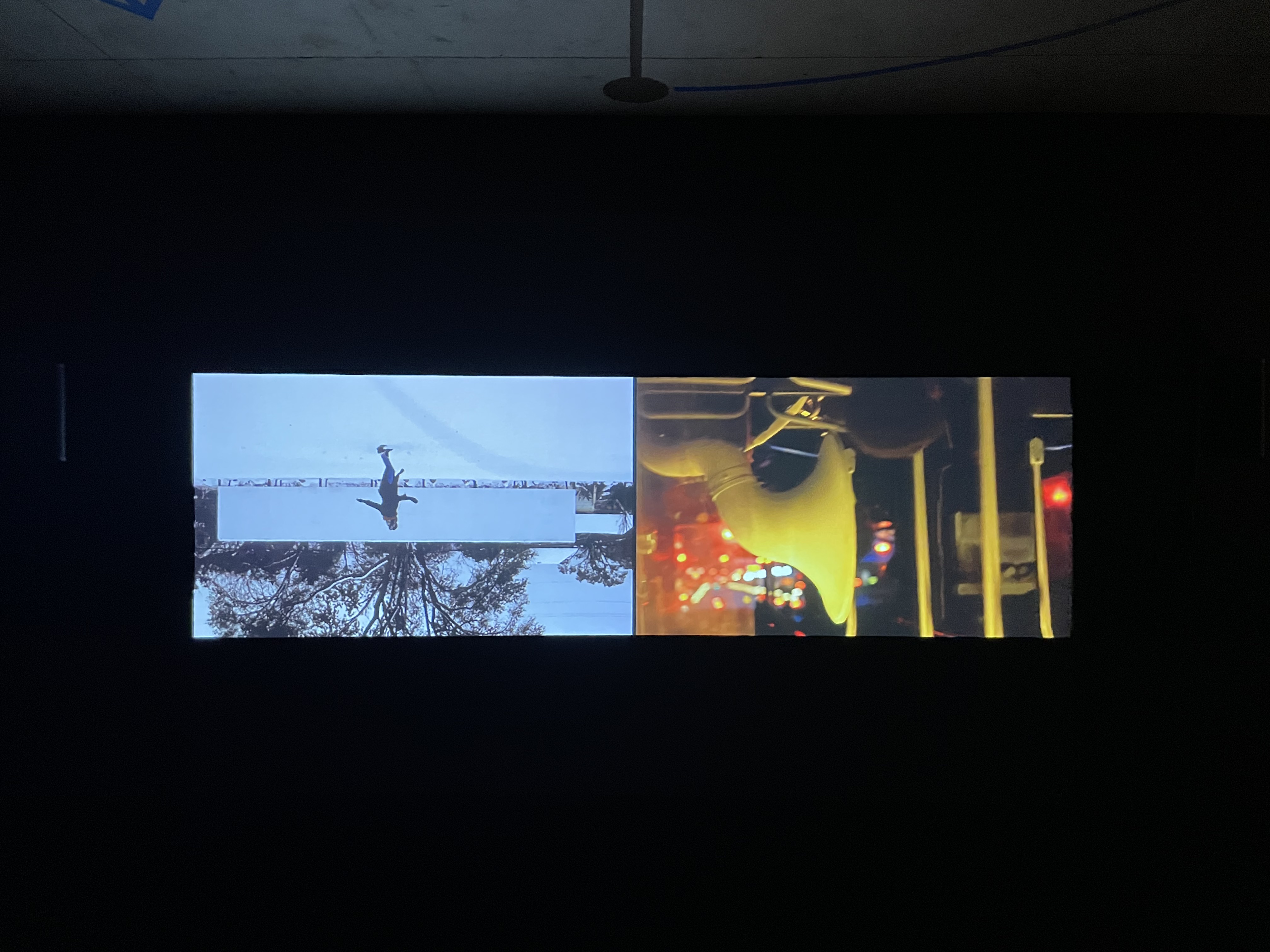

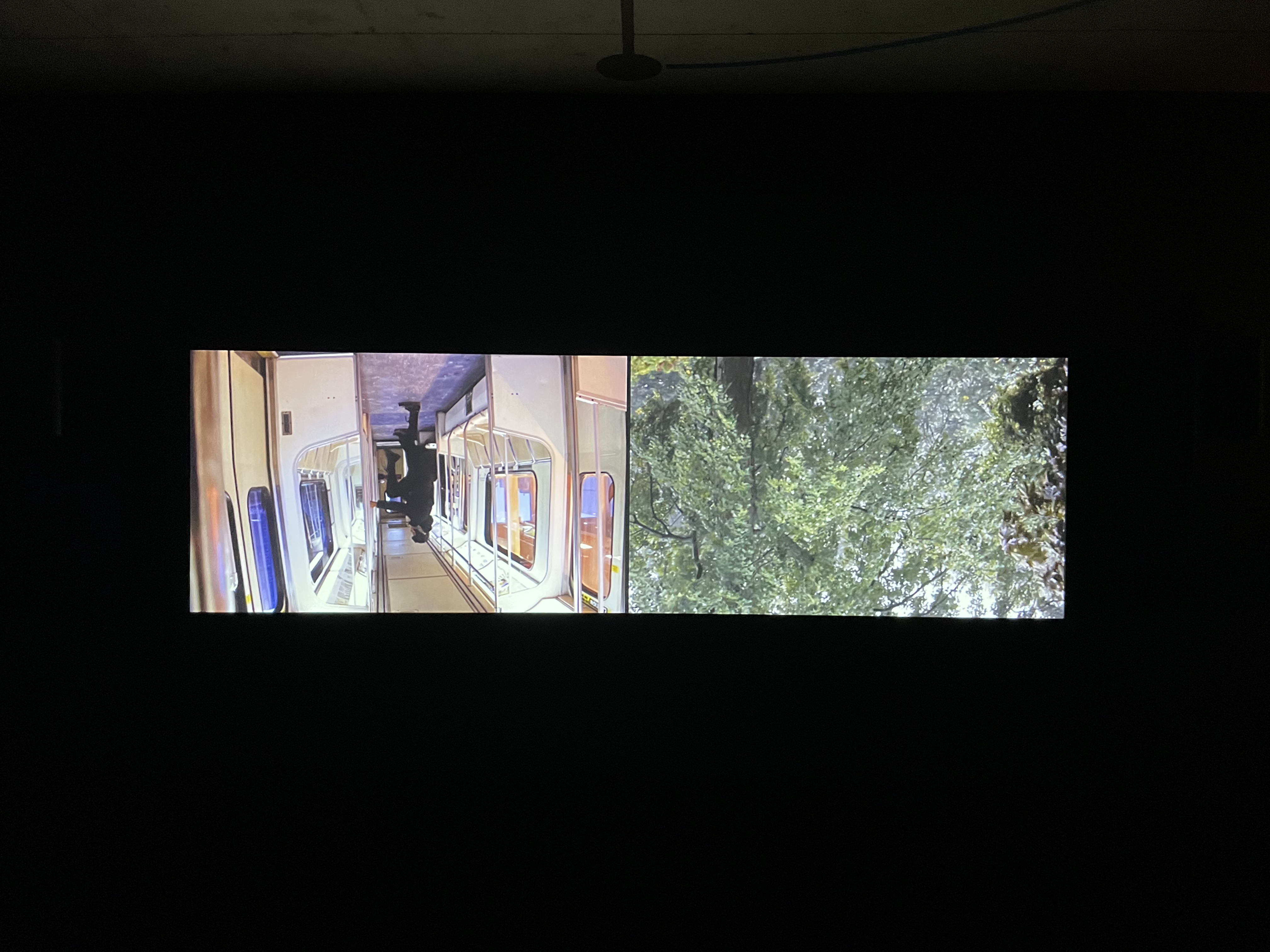

Amongst these organics, we’re fed intermingling shots of infrastructure: buildings, buses, the people mover, in all their drab familiarity. Anonymous brick, cornices, official looking seals. These mundane structures protrude awkwardly from the footage of bodies, mostly the artist’s own, dancing outside, in an apartment, on the street, in the train…It is a timely piece, both historically, but also in how much time is held within it. Footage culled from roughly ten years, one can feel that time the artist spent breathing, moving, thinking, dreaming, inquiring, looking.

Everyday occurrences of bodies riding the bus, cooking dinner, tending a garden, dancing in the snow, are given new vitality. The artist’s movements are sweeping like a tide. And the rhythms of the sounds, the editing and the dancing is all connected in its gentle fluidity. As a viewer, I become increasingly aware of my own watery interior, the sac of flesh, blood, and organs that “I” am currently residing in. Thinking these thoughts, I am enveloped deeper into gant’s tide, and the realization that we are all bodies of water…

“As watery, we experience ourselves less as isolated entities, and more as oceanic eddies: I am a singular, dynamic whorl dissolving in a complex, fluid circulation. The space between ourselves and our others is at once as distant as the primeval sea, yet also closer than our own skin—the traces of those same oceanic beginnings still cycling through us, just pausing as this bodily thing we call mine. Water is between bodies, and of bodies, before us and beyond us, but also very presently this body, too.”1

Wend is hypnotically liberating in a way that conceives an alternate reality through pacing, layering and editing. There is a blunt truth to the sequences as footage of packed busses re-appear, people crammed shoulder to shoulder, no one speaking. I can smell the stale boredom. The forced performance of business. The mundane authenticity that these moments capture portray the heartbreaking reality of the things our bodies, and our souls, must endure in 21st century capital.

This conversation around our lack of bodily awareness in Western cultures has become increasingly relevant to artists and theorists like Cally Spooner, the author of Rehearsal, published by Mousse Magazine. “In Western society, the perception of much of our bodies has gone missing. This loss is not accidental. It occurred because intolerable psychic conflicts are suppressed when an individual under-responds (and eventually fails to respond) to their instinctual needs. Such needs might have been obstructed and replaced by performance principles, principles that proceed, perhaps, from the chronormative swing of a pendulum clock in 1657, from the timely running of British trains in 1840, to the French prison timetable in 1838, to Hollywood’s frame rates, to Instagram refresh rates—all regulating goods, images, prisoners, and people with a Western undulation, not elicited from the bodies it holds and measures.”2

This business as usual is the lifeblood of our society. Seen on the bus, any bus, every bus, shoulders slumped, body weight uneven, people carrying the physical pain of trying. Trying. Trying constantly to arrive on time. Sara Ahmed, writer of Queer Feelings describes this beautifully. “Regulative norms function in a way as ‘repetitive strain injuries’ (RSI’s). Through repeating some gestures and not others, or through being oriented in some directions and not others, bodies become contorted; they get twisted into shapes that enable some action only insofar as they restrict capacity for other kinds of action.”3

In gant’s work, we are reminded that to move freely, to re-turn to water, can act as a potent antidote to the monotone clicking of capitalism. To allow our body to facilitate the motion of our humanity, which is not linear, or direct, or white, or heteronormative, or categorizable, or quantifiable. The magic of Wend is that it delivers so much because it doesn’t do too much. It gives space to breathe, move, think, dream, inquire, and see.

bree gant’s Wend is on view at Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit until March 26, 2023.

1 Astrida Neimanis, “Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water” in Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice, eds., Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni, and Fanny Söderbäck (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 85.

2 Cally Spooner, “Rehearsal” Mousse Magazine, January 18, 2023. https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/rehearsal-cally-spooner-2023

3 Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 145.