Michael Lask and Rick Manore, narrated by Ashley Cook

April 18, 2022

The history of art in Detroit encompasses the story of C-Pop, an exhibition space that started when Michael Lask responded to a Metro Times ad about old concert posters. The ad was posted by Rick Manore, who was born in Toledo, Ohio but grew up in a small town called Ida, Michigan across the street from Gertrude Crampton, a renown children’s book writer who wrote Golden Books’ Tootle the Train and Scuffy the Tug Boat. That detail is not necessarily important to this story, other than to point out that Rick Manore is the second most famous person from Ida, Michigan.

When Rick posted that Metro Times ad, he was a functioning art dealer in Metro Detroit, but before that, he was working midnights at a credit card company after moving back from California.

Rick Manore: While I was in California, I was on the verge of becoming a media mogul. But the thing is, it was about timing. We were being represented by the biggest agency in Hollywood, Creative Artists (CAA), and before streaming came in, we found a legal way where we could put real radio stations all over cable stations. That’s what we planned to do, but our timing was bad. If we would have been there a year earlier, it would have been great...

After that didn’t succeed, I moved back to Michigan with my tail between my legs. But while living in California, I learned a lot about art through my mentor Deborah Jacobson, who owns a very important art gallery out there in LA.

The gallery of Deborah Jacobson opened in 1973 and is called L’Imagerie Gallery located in North Hollywood. They exhibit and sell original artworks and prints with a particular focus on rock concert posters from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Michael Lask: Okay, back to the history of C-Pop.

Rick: Yes, it all started with a friend of mine, Mike Wolfe, buying me a bunch of concert posters. And that’s really important because without Mike, this doesn’t happen.

Michael: And then I got into it right after that.

Rick: Yes, Michael Lask was one of my clients. At that time in 1992, he was a collector of 1960s art and was also a big fan of the music of that era. That’s how Mike and I met; I used to go from house to house selling posters to my clients.

Michael: An important detail to this story is that the San Francisco art scene in the 60s and 70s was enormous for its concert posters. There have been many books on it, it’s legendary!

So I answered an ad that Rick put in Metro Times to purchase some of these vintage rock posters. My wife thought this was crazy because Rick was a complete stranger, but anyway, he came to the house with a pile of posters and we went through them. I bought a few and that’s when we started talking about a gallery right then and there, and Rick ran with it.

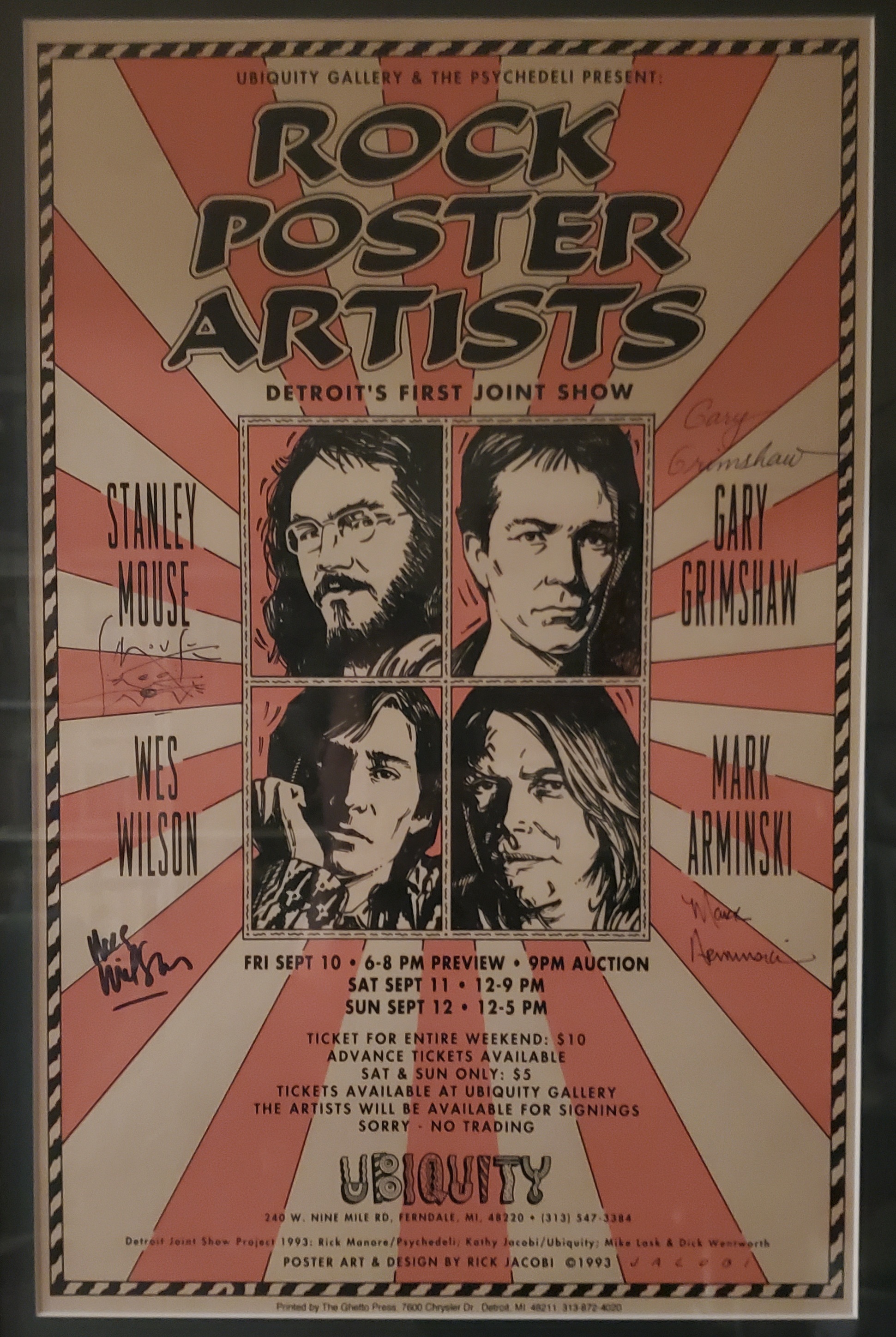

Before acquiring a location and officially opening C-Pop, Mike and Rick organized an event at Ubiquity in 1993, a gallery space in Ferndale, Michigan that was run by Kathy Jacobi. The event was a joint poster show featuring the works of artists Stanley Mouse, Gary Grimshaw, Mark Arminski and Wes Wilson.

Michael: Even though Kathy Jacobi supported it and her husband even created the poster for the show, the event led to a difficult relationship between us and them because she wanted to have her own thing and we came in with this entire train of stuff. We completely overwhelmed her gallery!

A “joint show” was a popular exhibition format in San Francisco in the 1960s and 1970s; the phrase “joint” acted as a double entendre, but ultimately meant it was a group show with different artists’ posters.

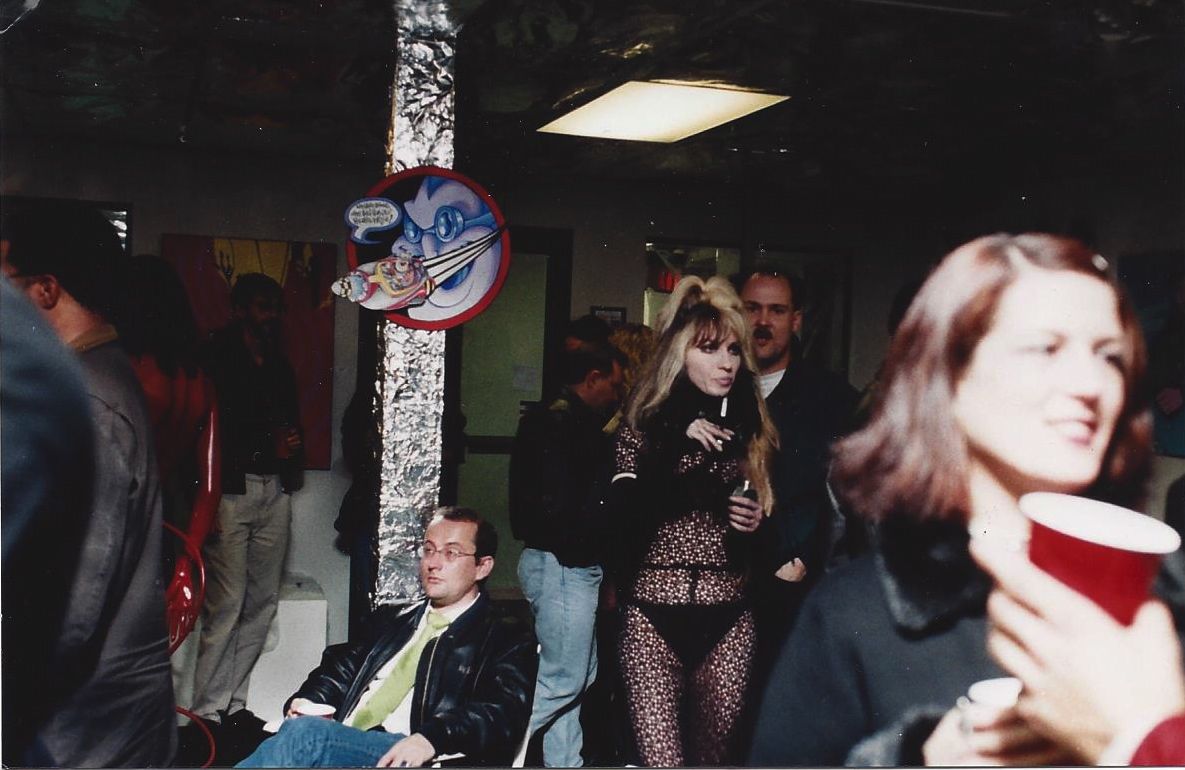

Michael: Joint shows were a tradition in the world of posters, and we brought them back! It wasn’t long after that we opened our own space. Once we had the space, we started bringing in artists and our shows ended up becoming major party events.

Because we were doing these shows and they were drawing a lot of attention, we began having opportunities to go out to San Francisco to do rock concert posters events out there, so we did that a couple of times. It was a crazy time to be hanging with all of these people; I can still remember doing that first show at Ubiquity and I had a Jefferson Airplane poster that Wes Wilson had done. It was already in the frame but Wes walked in the door and within 5 minutes, I took the poster out of the frame and had him sign it.

We would do concert posters with Gary Grimshaw frequently, and before you knew it, the whole concert poster thing was back. Arminski did all kinds of these posters with us too. Along with the posters, we did handbills, which was also a tradition from back in the day.

Rick: To touch back on the topic of the joint poster shows, the double entendre of using the word “joint” was significant because you would have to remember, back then, this stuff was not online, it wasn’t even in the newspapers. The promoters were smart and thought “we know our market”, and at that time in the late 60s, it was kids who liked to drop acid and smoke and eat mushrooms and have a good time. Peace, love and I don’t want to go to Vietnam. These joint shows and these posters became like beacons. People who didn’t care for it, like the over-30 crowd, would just walk right by, but if you were in tune with that vibe, you would see it from a mile away. It was sort of art-nouveau meets street advertising.

We also have to keep in mind that many of these artists did other things as well. They did album covers and posters for instance, but they also did more traditional forms of art and illustration. For instance, Rick Griffin, the greatest of all of them, did underground magazines alongside Robert Crumb, Stan Rodriguez and all those great comics, but he also did posters. He was probably the most talented, but he tragically died in a motorcycle accident right before the big surge of his work. Detroit, next to San Francisco, had the best rock art poster history; the Detroit posters were actually even more collectible than the ones made in San Francisco, because there were less of them and they weren’t merchandised by Bill Graham.

Bill Graham was a German-American impresario and one of the best know rock concert promoters in the United States, working from the 1960s until his death in 1991.

Michael: A cool thing to note too was that these Detroit rock concert posters were actually done by local Detroiters, primarily Gary Grimshaw.

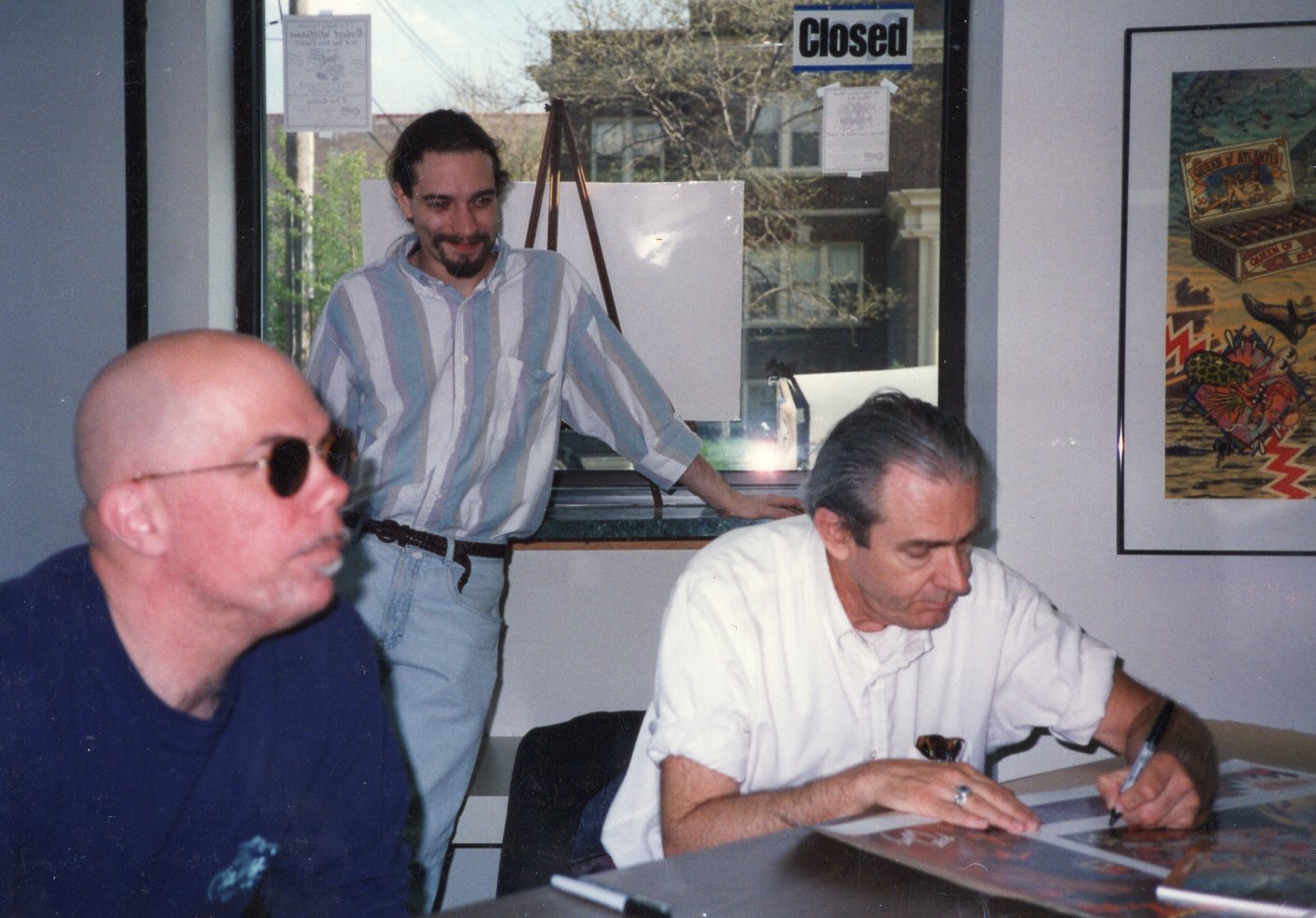

C-Pop’s first gallery space started out in June of 1995 in the basement of an old church in Royal Oak at 6th and Lafayette after the space had been remodeled for retail. They started off with their first show being rock concert posters, however Rick had much grander ideas than that. Because of L’Imagerie, the LA-based gallery of Deborah Jacobson, they were able to bring stuff in from Los Angeles on consignment which led to their first major art show being by Robert Williams called Grab Your Ankles, Detroit.

Rick: Our first major show was by an artist named Robert Williams. He was a cartoon surrealist. He was one of the first people to take cartoons and turn them into fine art. I knew we were a new gallery and we needed to make a big buzz somehow, and I knew we could get the underground papers like Metro Times and of course, Orbit gave us a cover for Robert Williams.

Funny thing is though, I could have gone in a totally different direction with the gallery, and almost did! One of our clients who was buying posters from us at the time was a probate attorney in Chicago. Anyways, for whatever reason, at one point he became John Wayne Gacy’s attorney.

Interestingly, when Gacy was put to death, as a payment for doing his probate, in his will, he gave the lawyer all of his personal art. And John Wayne Gacy was known for his art, it was like Jack Kavorkian; they knew his art, they saw his art. We had this connection with this lawyer who had the entire art collection of John Wayne Gacy, which also included other serial killer artists’ work. All of the serial killers talked to each other and exchanged art, so in the collection were artworks from people like Charles Manson, Ed Gein, Richard Speck, all these famous serial killers. They all traded their art with each other. If we went in that direction, our first association with C-Pop was going to be with a bunch of serial killers art. I was thinking, it is interesting but maybe isn’t the right direction, so we went with Robert Williams instead, who was underground and controversial in his own right, but he was a first rate painter.

Michael: It was an easy call for me, I mean, I didn’t even know who Robert Williams was but I was pretty sure I didn’t want our first show to be the art of a bunch of serial killers.

Having Robert Williams as the first gallery exhibition outside of the joint poster shows was a smart move, but what made it really work was their opportunity to take in the stock of another great artist at the time, Derek Hess, who was also represented by L’Imagerie.

Michael: Deborah Jacobson sent us art by Derek Hess and other great artists. She would also send us Warhols on consignment. At one point I had a giant Warhol painting hanging in my house, in the dining room; it was Geronimo. I wanted to buy it but my wife wouldn’t let me because she didn’t like the image; she wanted the flowers but it wasn’t available. Needless to say, now we greatly regret not buying it.

While doing poster show tours, we became friends with Marty Geramita from Cleveland, Ohio. He helped supply us with all the younger guys that I didn’t know, like Frank Kozek for example, who was like a Warhol at that time; he was pretty amazing. Debbie helped Kozek with his career similarly to how we helped Mark Arminski.

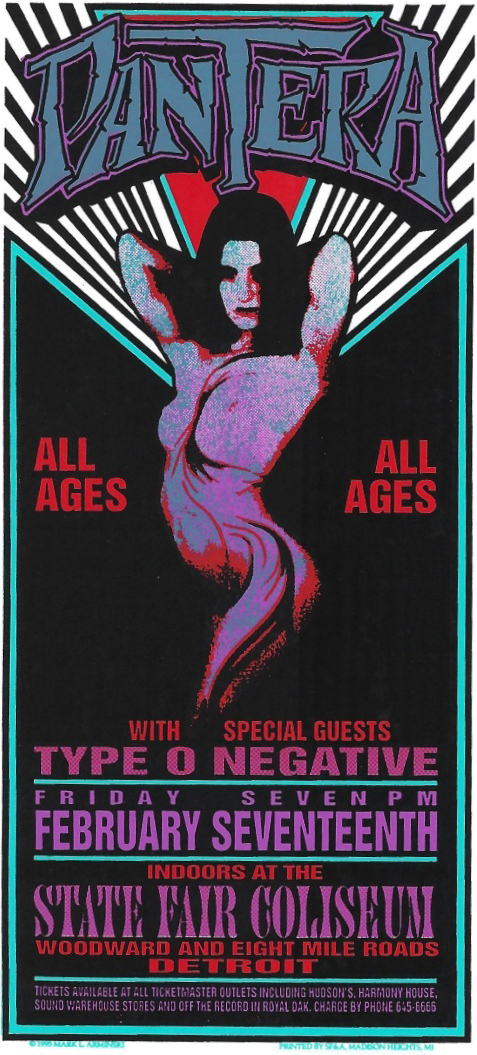

The big second wave of concert posters started coming out in the late 80s, early 90s. There was a place in Detroit called The Ghetto Press who did silk screen printed posters. They started working with Mark Arminski.

Rick: Speaking of Mark Arminski, we missed a whole key part of the story behind Detroit concert posters.

The big second wave of concert posters started coming out in the late 80s, early 90s. There was a place in Detroit called The Ghetto Press who did silk screen printed posters. They started working with Mark Arminski and I saw an opportunity to offer to front the cost for printing and get the OK from the venues to show them at C-Pop. We set up a situation where the Ghetto Press printed them and I cut a deal 50%/50% with the artists even before cost, which was stupid on my part, but we always took care of the artists we worked with. So anyways, we published 60 of Arminski’s posters and that kind of helped him get a pretty big name in the poster business while also helping us build stock of his artwork to show and sell.

The thing about rock posters is that they have a three pronged approach to attract people. Number 1, they like the band. Number 2, they really like the art! Number 3, they have the memory of being at the concert.

At that time, working directly with the artists of the posters was a safe approach to ensure they would gain access to publish and sell the concert posters, however eventually there became many other people who wanted to have a say regarding how the art was used and who had the rights to sell it.

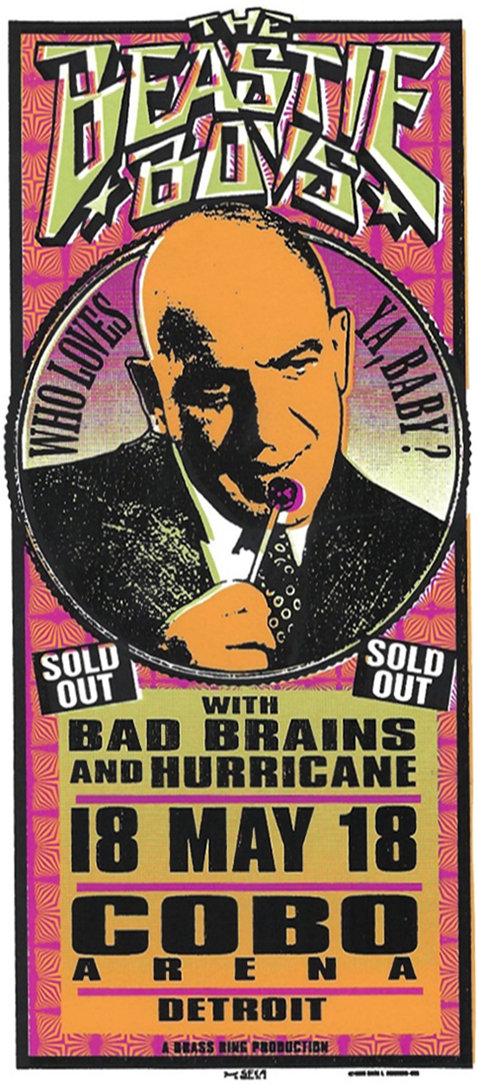

Michael: So we ran the gallery and we worked with the artists and the printers in order to get these posters produced. There were many times when we made posters for bands without necessarily having permission from the bands to make and sell the posters.

Rick: Yes, there was a period when you could fly in that gray area. We did it mostly for the promoters, that’s how we got around it. We skipped the bands and went directly to the promoters. But that became tighter, because later, you would have had to use the record company’s imagery; you weren’t free to design whatever you wanted anymore.

The way we got access to these posters was kinda sneaky. Some of these bands would not allow us to work with artists to design, show and sell posters for their concerts, even if you gave them half of the prints to merchandise themselves. Some of the bands would actually be open to it, but then their lawyers would say no because of the merchandising contracts of the band. I would often select the more up-and-coming bands for this reason. Some of the venues that were hosting these shows for these bands on the posters were Royal Oak Music Theater or COBO Hall...we generally didn’t sell the posters at the venue though; we allowed the venue to use their own for promotion.

Of course, originally, these posters were made for promotional purposes but the market started wanting them as collectibles so that was why they got into the business to begin with; to offer them as collectible products for the market, sold through C-Pop in tandem with original artworks. As they continued working with artists to produce and exhibit the work, the artists were gaining recognition on a more global level.

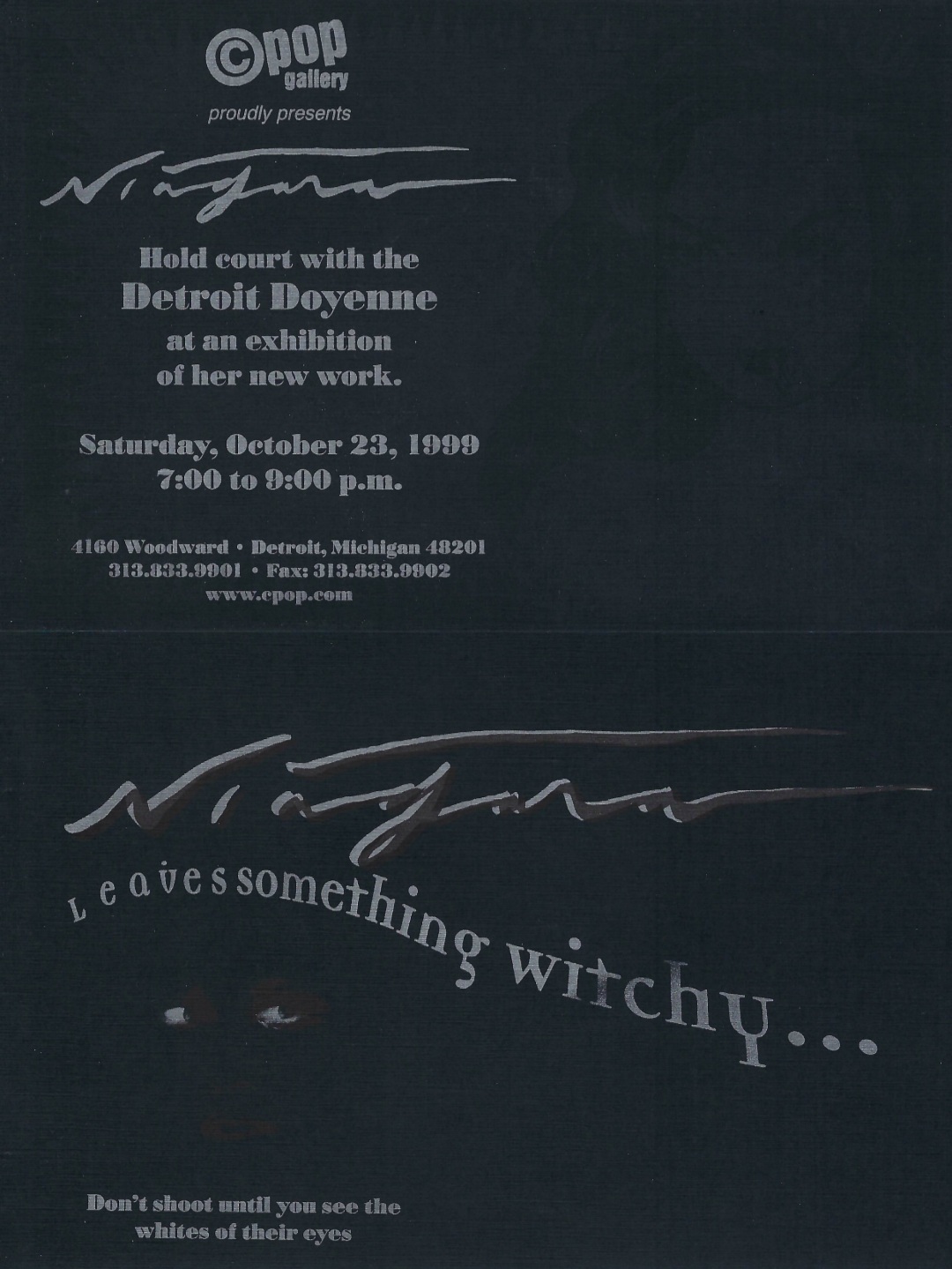

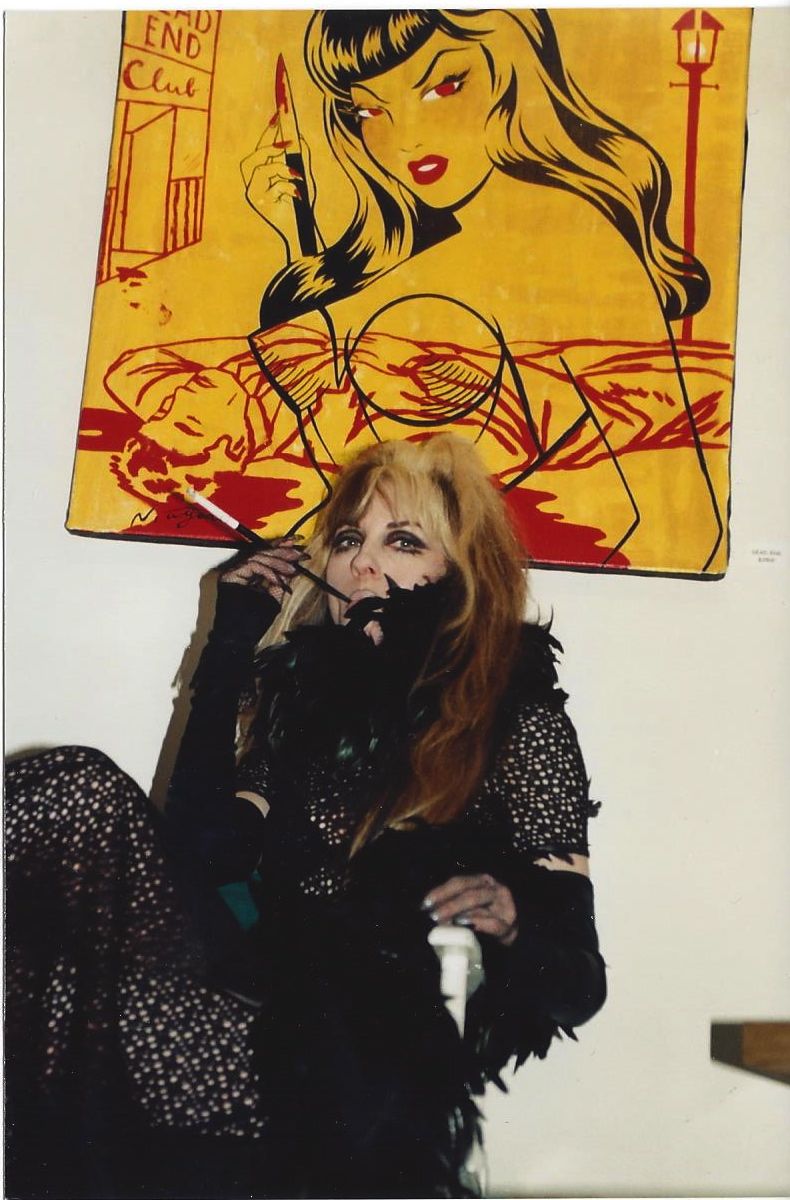

Rick: Royal Oak C-POP was where I first got the internet. Luckily, I had a young person working with me who understood the internet enough to work with it, and ended up being responsible for getting Niagara and Glenn Barr connected to opportunities in Japan and Australia. Niagara has made a lucrative career out of her connections with the Japanese fashion industry. The fashion brand is called Hysteric Glamor; they do a whole line using her imagery. Nobu, who is the person who started Hysteric Glamor, was also actually in that film Lost in Translation, in the karaoke scene, the guy with the really long hair.

Anyways, we also gave Tristan Eaton his first show, who is now a very successful artist. I mean, it didn’t take rocket science to see that there was an amazing amount of talent in the city of Detroit.

We also started working with Glenn Barr after they came back from LA where they were doing all the background art for Ren and Stimpy. We also worked with Tom Thewes, who was actually probably my favorite artist in Detroit.

Aesthetically, the posters and artwork that was shown at C-Pop fell into a category or genre called “low-brow” art.

Michael: “Low-brow” art became popular in the 60s in California, but I would say we sort of brought that to Detroit. I thought the best thing that we did was to highlight local artists working in that way, like Niagara and Glenn Barr. This “low-brow” aesthetic also translated to how we installed art; nowadays, they measure everything so that the work is hung evenly and stuff, but back then, we were just slapping things on the walls.

Rick: And of course, I was always a fan of the aesthetic and social implications of the Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937 in Germany. It influenced our approach to installation of work as well as the artists we curated into the gallery.

Michael: And, don’t forget about Tyree Guyton. We worked with him as well.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition seems to have influenced the “low brow” aesthetic in many ways, as many who practice in this way reference it. It may have had such an influence because it presents a historical anchor that actively challenges the idea of “high” art in relation to alternative ways to product and exhibit. The “low brow” aesthetic can be easily found in Detroit and other places that have a reduced presence of “high” culture to influence aesthetic decisions of artists and other players. Tyree Guyton is an example of an artist from Detroit that has actively made work from this place throughout his career and is widely recognized for his contribution to the world of this creative aesthetic.

Rick: In relation to Tyree Guyton’s work, I used to refer to Detroit as the new Munich because of German Expressionism. Munich was a dark, horrible place after World War I and was completely destroyed during World War II. This is another important factor that influenced me and my approach to curation; art does not come from nice places, it comes from living in the great wrong place.

One of the reasons why I moved to Europe in recent years was because I feel that there are some very important places, with the first one being Munich after WWI and second being Detroit after the riots. When the place is horrible, the artists move in. When you have ruins, it’s cheap, you move in, you glorify the area, then it gentrifies and then the artists realize they can’t afford their studio anymore and then they move.

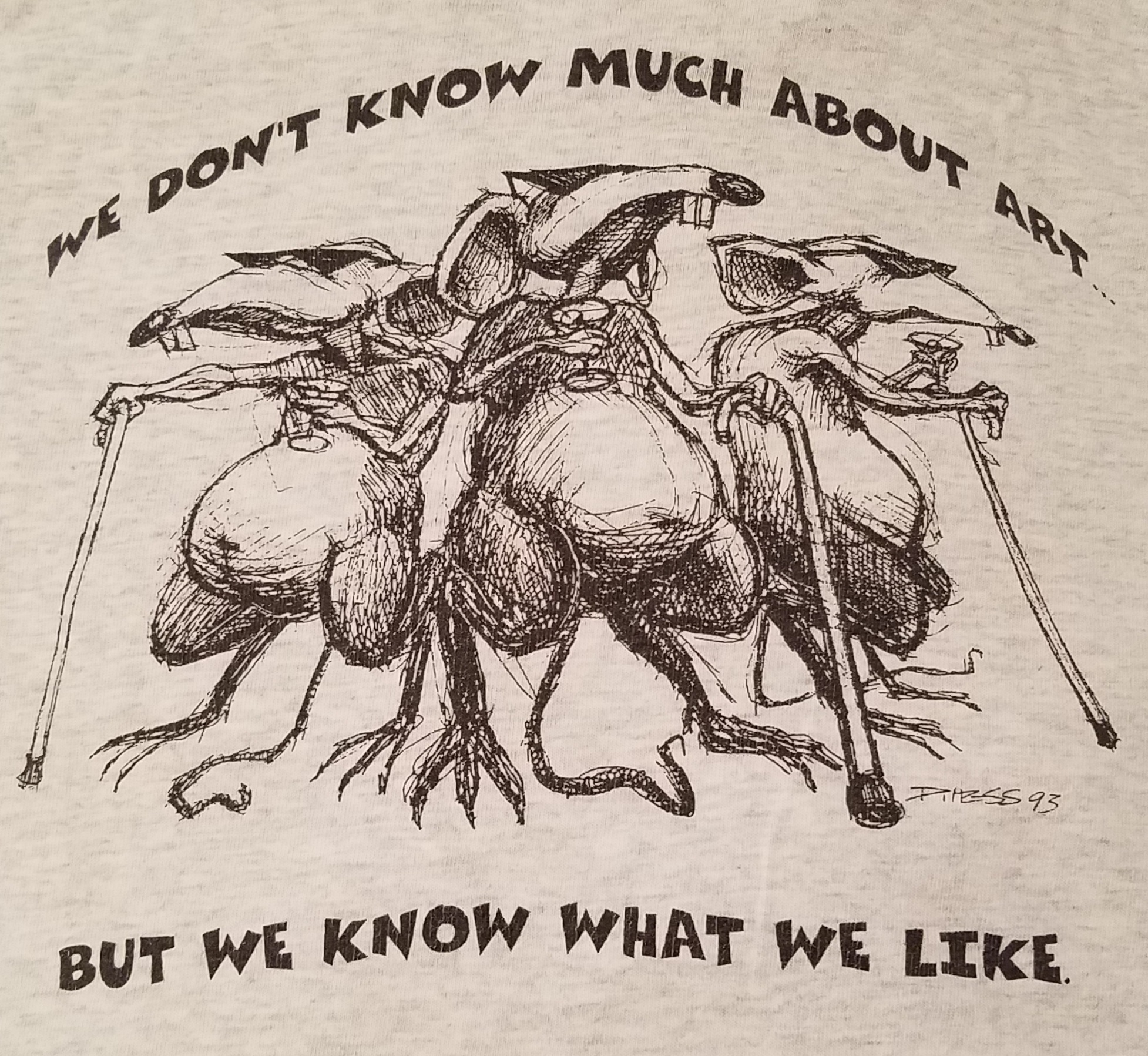

Michael: We ended up getting sort of gentrified out of our space in Royal Oak and then we got bought out by one of our artists Tom Thewes. It was the same artist who did our logo; the three blind mice logo I think.

Rick: No, it was Hess who did the mice. Then it was Michael’s idea to make the C the copyright symbol.

Michael: The mice one is what I liked, but you’re right, that was Derek Hess. We sort of went between the two logos consistently.

Our motto was we don’t know much about art but we know what we like. The truth is though, that Rick knows a lot about art. And Marty as well.

Rick: The copy-right symbol in the initial logo was significant because our original name was Creative Pop Management Inc. I didn’t want to call the gallery Creative Pop because it felt really pretentious, and I was looking into underground music culture and so I literally took the idea from Sub-Pop.

Michael: The three blind mice concept was so perfect too because it sort of stood for me, Rick and Marty. We all thought it was clever. Anyways, the name was attractive and sort of lent us to become a party scene; our shows were parties. We usually had live music at the shows with refreshments and such.

Looking back at the experience, I think our biggest positive attribute was also our biggest negative; we were too friendly with the artists. We got along very well with the artists and they were very happy working with us but we cut a very large percentage of sales to them. It was great, we thought, well, it was the artists who did the work and they deserved this cut...While we were hoping to cash in on numbers, we really did not see much of a return to the gallery financially.

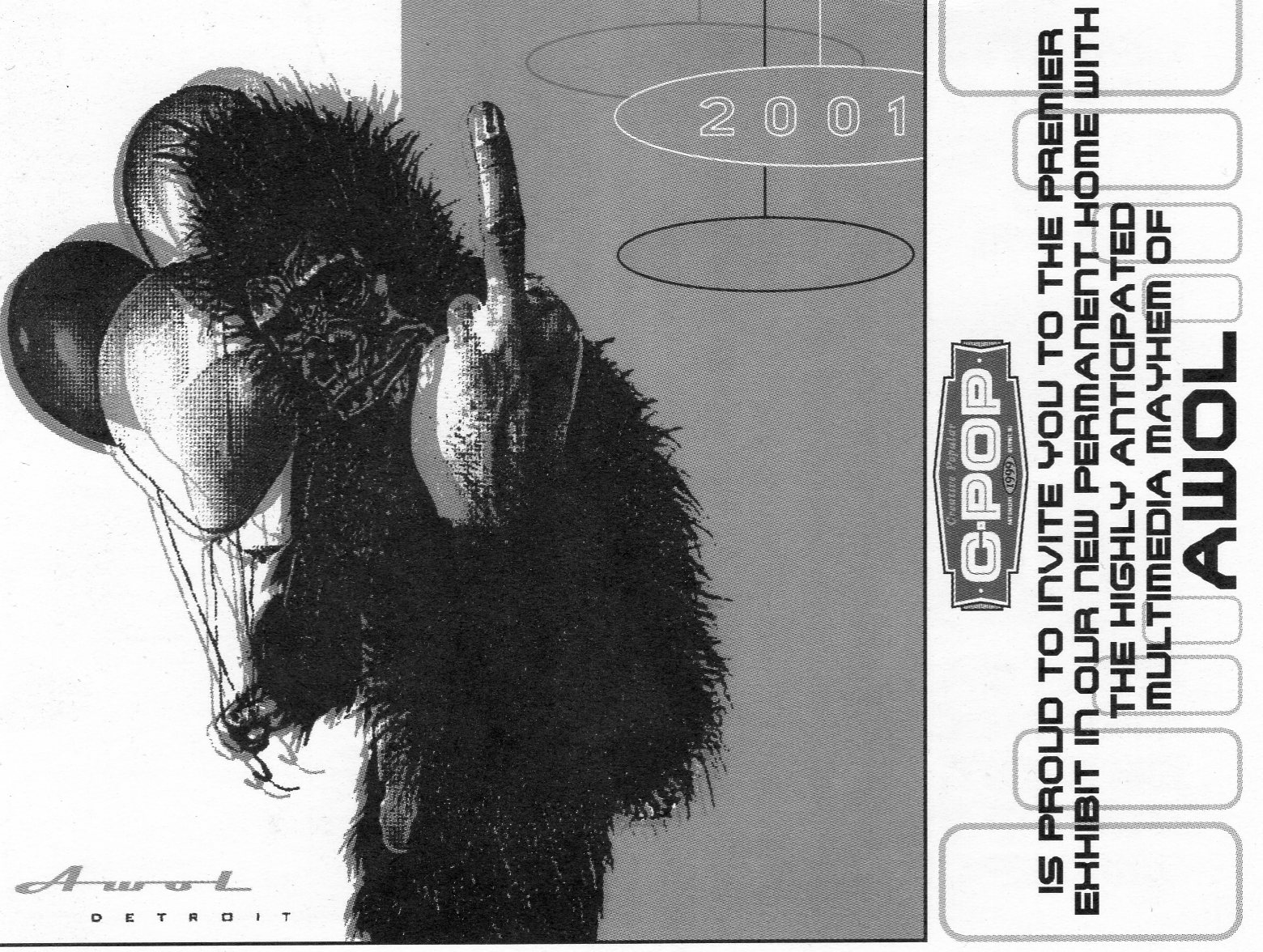

We haven’t gotten to the point where we talk about how the gallery became a multi-million dollar gallery. We had one of our artists, Tom Thewes, who was very interested in buying it from us. He bought it in 1998 and moved it to the Detroit location on Woodward Avenue in 1999, right next to the Majestic Theatre. I actually tried to talk him out of buying it!

Thewes turned out to come from a family with money, and it was perfect timing because we needed to close it up. We were losing so much money. In fact, I consider this one of the greatest things I ever did as a lawyer; I negotiated the sale of this gallery where we didn’t lose any money, we didn’t owe anybody any money and the gallery continued on. We even almost retained a percentage of it, but at the last minute the new owners decided that they wanted to have 100% control. They did keep Rick on the team however.

Rick: Yes, I was employed as the gallery director after this sale.

Michael: For years after they sold it, I remember going there for events and they spent so much money rehabbing that building to be like 3 or 4 levels. I remember warning him about it beforehand, saying “you know you’re about to do all this, but you really need to know that this isn’t going to make any money.” I threw all the cards on the table because I didn’t want to feel guilty. We called it “the multi-million dollar C-Pop” because it cost a million dollars to renovate!

They ended up closing in 2009.