Stephanie Kang

March 28, 2022

“The total energy of a system, however chaotic, remains constant.” – THREE BETRAYALS

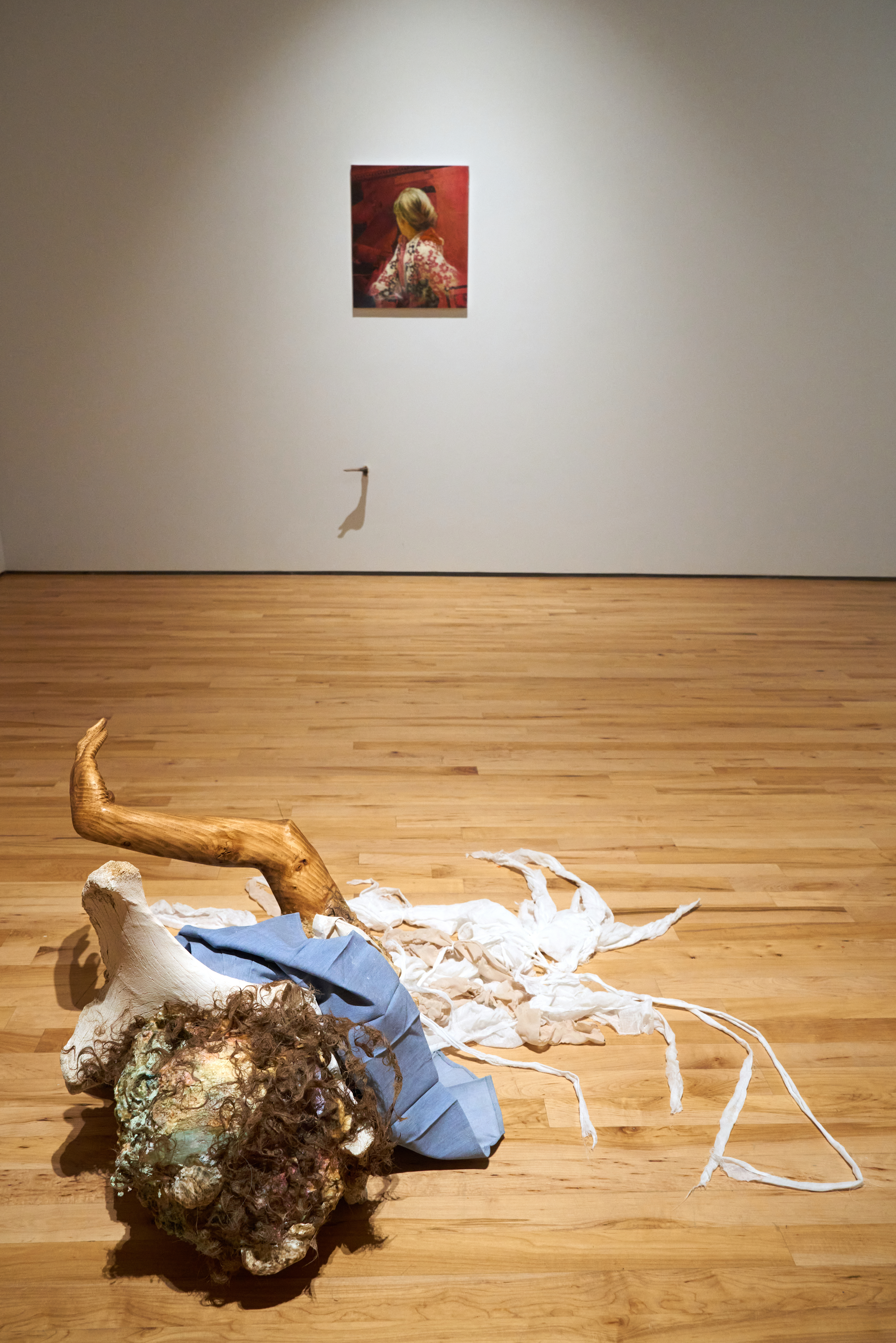

Upon entering the space of the gallery, the viewer is confronted with Catalina Ouyang’s Scorn of God (Quinn), a sculptural assemblage that resides somewhere between the recognizable and enigmatic. A single leg extends into the air, bent at the knee with its toes tensely stiff. Tufts of hair emerge along its backside, crawling up its rear with oyster shells embedded into the matted curls. Circumventing the piece, viewers can continually discover new elements that make up this anamorphic body. A shockingly bright blue horn protrudes from its genital region, like a phallic tongue emerging as an additional appendage. Pleated material covers the top-half of the body with long extensions of crinkled red fabric strewn across the floor, like bodily fluids or organs escaping their internal confines to form new tentacular connections to the surrounding environment.

The sculpture’s toes strategically point towards the gallery’s second space, an enclosed room that introduces new realms of Ouyang’s interconnected world. A second body Kick Madonna (Crystal), formed with wood, animal bone, and a collection of other materials, features a raised arm that emotes a spirit of desire and longing. It reaches towards the opposite wall, which displays the painting Betty (Relapse Selfie). Viewers might recognize the woman in the portrait as Gerhard Richter’s daughter, who he often returned to as a subject in his work. In the original version of Betty (1988), the German painter depicted his daughter turning away from viewers, refusing to meet their gaze. While living in the Midwest, a period in Ouyang’s life when they first experienced addiction, they would often visit the St. Louis Art Museum, where this painting currently resides, to reflect on its power and personal resonances. In their readaptation of Richter’s work, Ouyang superimposes Betty over one of their own mirror selfies, which was taken during a recent period of relapse. Through this gesture, Ouyang and Betty meet each other’s gaze, interrupting Lacanian relationships between the subject and the other, of “seeing myself seeing myself.”

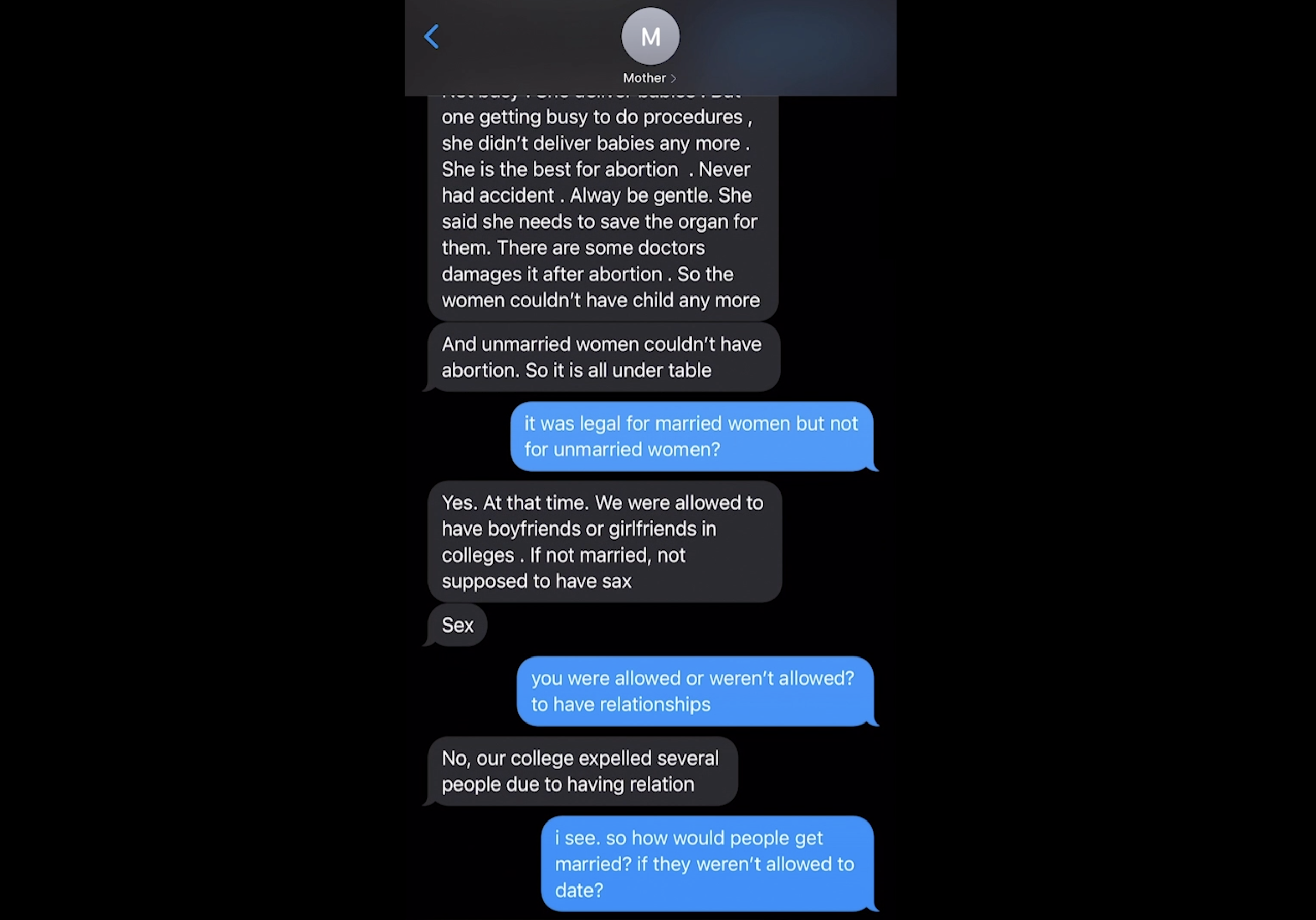

Each of the works in the exhibition stems from the video THREE BETRAYALS, which is the central culmination of Ouyang’s thought process. The forty-minute video pulls from a range of sources: theories of astrophysics, choreographed performances, home videos of the artist with their family, and documentary footage of the poet Anne Sexton. By juxtaposing these seemingly disparate elements, Ouyang positions the three-body problem, a concept within astrophysics that has no clear solution, as a framework for thinking through the body and its ability to retain transgenerational histories and secrets. One scene of the video shows text exchanges that discuss the artist’s grandmother, who performed abortions for unmarried women in China, including one for her own daughter (Ouyang’s mother). The conversation between Ouyang and their mother concludes when the artist asks who in the family was aware that their grandmother was doing these procedures, a question that their mother responds with, “We all knew.” By working through their own family’s secrets, Ouyang considers how the three-body problem can become a means of filling in the gaps of the unknown (“the shadow demons conveyed by one’s ancestors”), cycling through time and allowing it to fold back on itself. Through this process, one can create folds that provide new divergent solutions and sources of knowledge.

Throughout the video, three dancers carry out performances that reference these concepts. Dressed in pleated cloth, their bodies clearly reference Scorn of God (Quinn) and Kicked Madonna (Crystal), surrogate forms that capture their originators’ animated movements and textile attachments. Like their sculptural counterparts, the performers hide their faces, appropriating anonymity as a means of self-definition. As Glissant once stated, “We demand the right to opacity.” Their synchronized movements also allude to Deleuzian theory, which reimagines the body as infinite folds that can weave through compressed spatiotemporal pathways. The performers intertwine and fold into each other, allowing one’s movements to respond to the others. In the whirl of motions that fill the screen, they embody the three-body problem, creating chaotic and responsive systems that traverse time and space.

THREE BETRAYALS transcends linear time, moving back and forth between the past and present. It shows moments from the artist’s childhood alongside more recent footage of their mother and grandmother. Also, interspersed between these personal documentations are scenes from the life of Anne Sexton, the American poet who committed horrific acts of child abuse. Ouyang orients Sexton as a cipher within their work that exemplifies how they are “constantly approaching some edge of annihilation.” As the artist states, “I think there is something profound and complicated to be said for identifying with a so-called monster, even calling yourself forth to love a monster.” By collapsing their personal histories with Sexton’s biography and mathematical theories of motion, Ouyang explores the body as a vehicle of self-mutability, temporal transference, and rapturous discovery.

No Place is an artist-run gallery located at 1 E Gay St. in Columbus, Ohio. Established in 2012, No Place occupied a former mechanic shop in Merion Village and derived its name from a sign that once hung over the door - ‘No Place Like Home’. In 2021 the gallery relocated to a space in Columbus’ downtown area where it remains today.

No Place endeavors to exist as a conduit for a wide range of contemporary visual art to the Midwest, and seeks to present work that is vital to a broad audience. In consortium to regular exhibition programming, No Place is host to an expanse of DIY music shows, sound installations, talks, and events.

The No Place project indulges associations to the definition of utopia, and aspires to foster an integral community, while showcasing artists on a national and international scope. The exhibition space has been lovingly built from re-purposed and up-cycled materials and walls from neighboring art institutions. No Place is guided by the practice of re-imagining exhibition space, as well as the understanding and utilization of these resources: the economy of space, an earnest curatorial vernacular, as well as a comprehensive structure that invites greater discourse and participation.

Noplacegallery.com