Ashley Cook

June 8, 2020

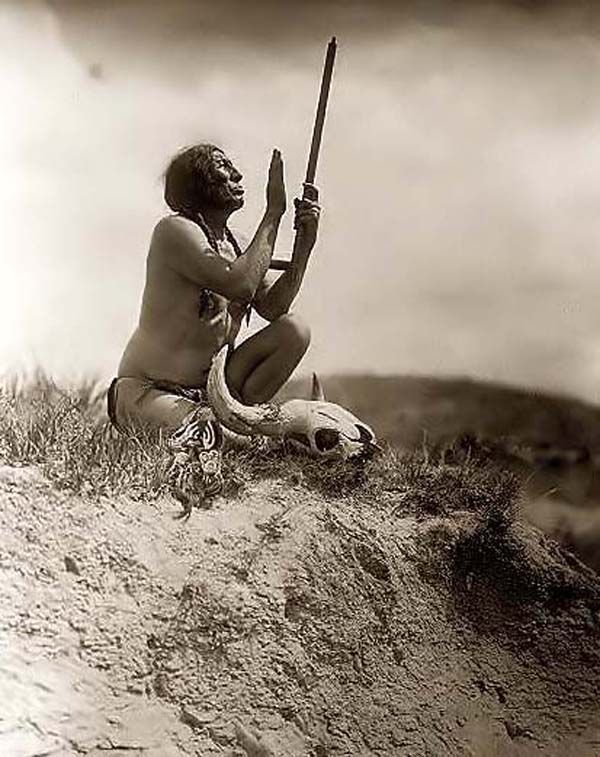

“Animism” as a term was invented by English anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor in the year 1871 with the release of his world renown text Primitive Culture. This text came at a significant time; just 6 years prior, in 1865, slavery was abolished in the United States after 246 years. Primitive Culture is 522 pages written to serve as a tool to formalize his “researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art and customs”. This text ultimately succeeded in presenting a positivist categorization of the belief systems of indigenous cultures whose societies were built on pre-modern understandings of human kind in relation to spirit and nature. The term “positivist” here refers to the philosophical movement of “positivism”, which is a system of ideas that confines knowledge strictly to observable and verifiable scientific data, inherently condemning any knowledge or belief systems that could not be proven through scientific measure; these “negative” belief systems were considered inadequate and meaningless. After the publication of Tylor’s alien perspective on pre-modern societies, the “animist” worldview began to be generally characterized by modern anthropologists to have a severe lack of ability to distinguish between human and non-human forms, which has been observed by studying practices largely involved in the attribution of human-like behavior and characteristics onto non-human entities, and vice versa. But this “negative” belief system, in its infinite variations, is one that served as a way of life on a universal scale, spanning continents from Africa to Asia to the Americas. Although each culture has its own unique mythologies and rituals, “animism is a term used to describe the most widespread and fundamental thread of indigenous peoples spiritual and supernatural perspectives, which encompasses an inherent connection between the spiritual and material world, attributing soul and spirit not only to humans, but also to animals, plants, rocks, as well as other geographic features including mountains, rivers, thunder, wind and shadows.”

The animistic worldview predominantly places the human being on the same ground, with equal footing, as other animals, plants and natural forces; furthermore, this perspective holds such a fundamental position in the way of life for indigenous people, that “their respective languages include no word for ‘religion’, and maintains an empathic distinction between ways of life in which economy, politics, medicine, art, agriculture, etc., are ideally integrated into a spiritually-informed whole”. 2 In Tylor's Primitive Culture, its immediate delivery announced the modern investigations of science to be formed on the basis that “inorganic nature recognizes the unity of nature and the fixity of its laws, the definite sequence of cause and effect through which every fact depends on what has gone before it, and acts upon what is to come after it [affirming that nature is] not full of incoherent episodes, like a bad tragedy...[and] nothing happens without sufficient reason”. 3 It would be appropriate to understand this text to be a founding product of modernisms attempt to free itself from the constraints of superstition that seemed to constitute the mechanics of “primitive” cultures. “To many educated minds, there seems something presumptuous and repulsive in the view that the history of mankind is part and parcel to the history of nature, that our thoughts, wills and actions accord with laws as definite as those which govern the motion of waves, the combination of acts and bases, and the growth of plants and animals...we may hasten to escape from the regions of the transcendental philosophy and theology, to start on a more hopeful journey over more practicable ground” 4

To the modern human, the belief system of indigenous cultures was seen as a world of magic, supernatural beliefs and confusion of boundaries; this perception was instigated by the growing influence of Christianity, the philosophies of Cartesian dualism separating mind and body, and the colonial expansion of Europe.

The influence of Tylor’s mis-representation of animism was founded in the progressive “purification process” between “nature” and “culture”, which provided him a platform to place animistic practices of indigenous cultures as “primitive”, creating a mirror in which to see themselves in relation to the “other”, “less evolved” cultures. There could have been no positivism without the negative to reflect upon; positivist thought fueling the modern description of the world relied, and continues to rely, on the imagination of a negative or “other”. Tylor’s concept of the “primitive” was then inscribed into an evolutionary scheme from the primitive to the civilized, in which civilized Europeans had evolved out of polytheism into monotheism, rising from nature to civilization, while the rest of the world’s people, described by Tylor as “tribes very low on the scale of humanity” had remained animist. 5 This evolutionary scheme would continue to spread into various aspects of society, one being the field of psychology, asserting that every human passes through an animist stage in childhood, a stage that is characterized by the projection of it’s own interior world onto the outside. Within psychology, the concept of “the primitive”, with direct recourse to Tylor, has continued to play a central role in the context of the theory of “projection”. Freud’s influence on the perception of “animistic tendencies” affirmed that it was simply a narcissistic view, asserting their inability to separate themselves from their surroundings because of an overly adorning love for themselves. For Tylor, establishing the term “animism” was an avenue to assert what is a “correct” and “incorrect” distance between matter (objects, things, nature) and people (souls, subjects, persons), with a continual focus on remaining in the modern present, ridding it of the archaic past. For psychologists like Freud, the establishment of “animism” was a way to determine the “correct” boundaries between inner self and outer reality. Outer reality became defined in terms of an objectified nature, uncontaminated by social representations, mimetic behavior, symbolizations and projections. In the marginalization of these “projections” that humans were making onto the outside world, they were simply placed within the field of psychology; everything that “primitive man” had projected outwards into the world needed to be subsequently translated into psychology in order to place them in “proper” fashion within society.

Amongst the reign of this positivist signification, the opponent is “wildness”; the “wild” posed a serious threat to the rationalist system, evoking panic as the foundations of modern power imagined the collapse of the boundaries it had installed. As the image of the animist “savage” served to unify the positive side of the Great Divide between humankind and nature, it was also used to inflict terror within the boundaries and borders of modernity; an image of a darkness that has yet to be touched by the light of reason, a space of negativity, a space of death. This “space of death” has long maintained a rich presence in modern culture as it is where the social imagination has placed its metamorphosing images of evil and the underworld. The struggle for Christianization and the induction of the space of death, also referred to as the Theatre of Negativity, was presented through martyrdom, and the experiences like the witch hunt, in its suppression of magic and the worshiping of many gods or talking with spirits; all of these gave birth to the European conception of “evil”. “This theatre would find ceaseless continuation in the Enlightenment and secular modernity, in the progressive exorcisms of all states of mind that resisted the Christian, and later, the modern discontinuity between humans and nature. The boundary of the modern world generated an imagery at its internal margins correlative to the colonial death space, but yet articulated in more familiar morphologies of the ‘night of the world’ what much later would become the ‘unconscious’. This space is populated by dismembered bodies, by fragmentation and scenarios of disintegration, providing a monstrous mirror of objectification, discipline, mechanistic fragmentation, and political terror” 6 The Theatre of Negativity served as a tool in further affirming the oppression of animistic world-views, practices of magic and idolatry, marginalizing any belief system outside of science, Christianity and rational thought, through the threat of jailing, torture and/or death. The logic of the Great Divide also found another method, for example, psychiatry and the asylum. The imaginations of animism under its modern definition once again allows for the maintenance of the power over anything “other” within the institutional machine. The boundaries of positivist thought invented superstitions, paranoias and anxieties that were presented in the forms of images of threatening mimetic infections, in which the order of positivist rationality is always at stake and secured by the extension of its rule, for example, all that are deemed sinners go to hell, all that are deemed law-breakers go to jail and all that are deemed insane simply go the hospital.

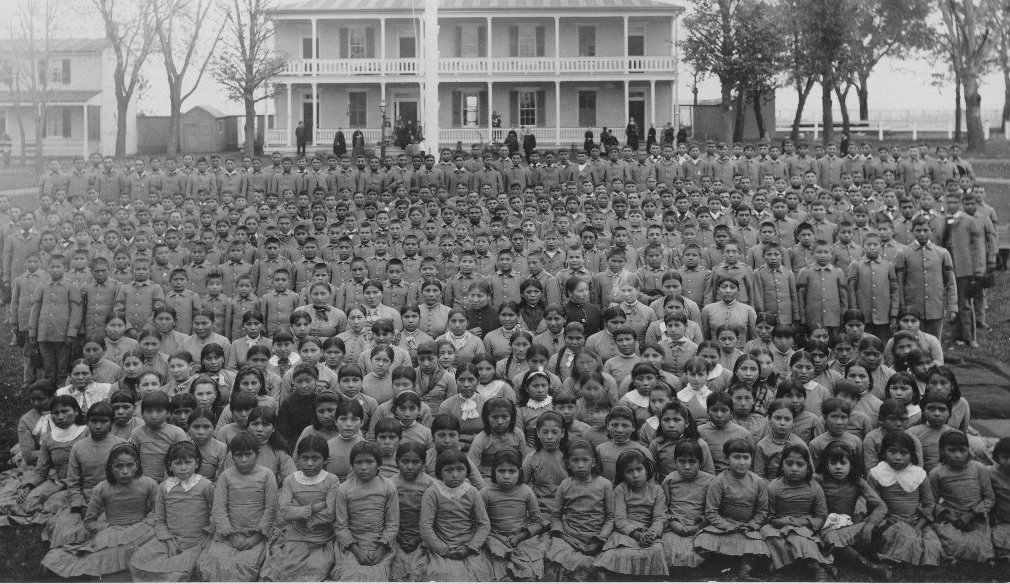

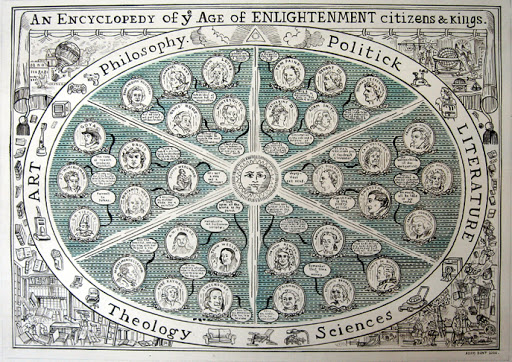

Modernity only found its stability through the objectification and oppression of animistic beliefs and the “other”, resulting in pointless wars, genocide of many indigenous tribes and cultures, and the widespread colonization of thoughts and practices. Then came the Enlightenment, which was a program that worked steadily towards the disenchantment of the world by dispelling myths and overthrowing fantasy with knowledge. The successful disenchantment of the world meant the final extirpation of animism, cutting off any remaining social and ties to nature and causing established representations of nature to lose their meaning; what modernism gained with this stance was the strict belief in the universality of scientific knowledge and rationality, and, above all, the freedom to manipulate and exploit nature in ways unfathomable in pre-modern contexts. The disenchantment of nature and the cultural marginalization of animism was effective to such an extent that “the world had been unified, and there remained only the task of convincing a few last recalcitrant people who resisted modernization; and if this failed, well, the leftovers could always be stored among those ‘values’ to be respected, such as cultural diversity, tradition, inner religious feelings, madness, etc. In other words, the leftovers would be gathered in a museum or a reserve of a hospital and then be turned into more or less collective forms of subjectivity. Their conservation did not threaten the unity of nature since they would never be able to return to make a claim for their objectivity and request a place in the ‘only real world under the only real sun’” 7.

149 years after the publishing of Primitive Culture, 401 years after the first 20 slaves were brought into the United States, here we are. It is essential, as we reflect on the contemporary structures of a society, to do so with an understanding of the way in which the ideologies that affect our lives from day to day were initially introduced and implemented. Since it’s inception, this machine that was built centuries ago has been incessantly forcing a takeover based on an ignorant and manipulative ideology, and we are all consciously and unconsciously influenced by the libraries, belief systems and fears of this machine. Everything that we know of history, we know because it further confirms who we are as moderns. The history that we use to map out and de-code what we do not understand has been a war machine between the negative and the positive, the premodern and the modern, nature and human, majority and minority. Through this insidious separation from nature and the disregard for the humanity of anyone considered to be more “other” than another, we are now facing the effects of a snowballing global climate and humanitarian crisis that seems to be leading to what we are now observing, in real-time, to be a coming insurrection that is long overdue. To rise and fight for the world we want to live in cannot go without the preconception that the societal structures that exist all around us are only constructions put in place and maintained by belief and fear, and just as they were constructed, they can be deconstructed, manipulated, destroyed or rebuilt. But, this dismantling would require a determined consideration of what a reversal or editing of the contemporary state of things would look like. And this would inevitably highlight the need for a persistent effort to recognize, stop and seek redemption for our exploitative tendencies, learn about new ways to appreciate the differences among us, restore a sense of oneness, and pursue a persistent attempt to reconnect, as the organic creatures we are, with the earth.

“What is beyond the immediate realities that the news media and our own shortcomings cement into the shell of credible fantasy that protects our nakedness? The unquestioning faith of primitive man, and perhaps of some people today, in a divine source, is a thing which has become increasingly unreachable, incredible, unsupportable in the face of the powers existing in the modern world. We wish to put on skins, to clothe the unspeakable, to fill the vacuum. A flood of irrelevant cliches, a panic to close the opening as though it were a leak in the dike which would let in the ocean and destroy civilization. We should trust ourselves to venture into this unknown wilderness beyond the confined walls of our civilization” 8

What would it mean, as contemporary moderns, to recognize these areas, the hybrids, the blocks of movement of something which is in transition between what it was and what it will be? As many contemporary philosophers and anthropologists are beginning to see this need for control as paradoxical and highly problematic, they are asking “how do we break from these tendencies?” And what kinds of potential comes with the suspension of our need for control? Every thought, desire, action, etc. is consciously and unconsciously determined by our understanding of ourselves in relation to the values and customs of the modern world. To be able to reassess how we deal with the unknown in modern culture and restore our abilities to be okay with what we do not fully understand requires a deconstructive approach to unveil how we became so weary of the unknown to begin with. This kind of autonomous state of being can only be achieved through a deterritorialization that plucks you out of your comfort zone and allows you to exist on the peripheral long enough to see the mechanical functioning of the modern machine and achieve a birds eye view of the areas to penetrate through to reach the notion of what it even feels like to be free. Any event of deterritorialization offers us an opportunity to study our own culture from the periphery, among the undefinable, to suspend investment of taste and transcend the boundaries of what we know to be “truth”. The process of taking a look at other cultures in relation to our own culture, and trying to dismantle the perpetual interweaving of existing disciplines seems so impossible in the modern world that it has been referred to as “untying the Gordion Knot”. The Gordian Knot is from an ancient Greek legend of Phrygian Gordium associated with Alexander the Great and has been used in language as a metaphor for an unmanageable problem which can only be solved by thinking outside of the box. Many of the citizens and people of the world seem to be ready now for this necessary deconstruction and unlearning to take place, in order to imagine a new kind of world.

Our sense of reality has become increasingly abstracted, pulled apart and stretched, particularly since 2016 with the election of Donald Trump as the 45th president of the United States. It has felt that we have all accidentally ended up on a reality TV show, or in an apocalyptic science fiction film, with unrest being a constant state in one way or another amongst various minority groups. What we understood to be a “normal” presidency was far from what we are currently experiencing; there is, however, a silver lining to any type of chaos, and in this case, the anomaly before us seems to have enhanced our willingness to pay attention. The complicit have actually started to monitor and the silent are beginning to speak out; as crimes of past centuries are becoming unearthed to share space with the misconduct of the now, the people are saying enough is enough. Needless to say, this discontent and sense of deterritorialization caused by this Twilight Zone of contemporary reality has triggered mass uprisings, and global movements have formed that are working vigorously to collapse the various toxic foundations in place. There has been the emergence of the mass climate strikes organized by 17 year old climate activist Greta Thunberg in order to raise awareness about global warming, the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment and sexual abuse, the Gay Pride Movement fighting for freedom and non-discrimination for LGBTQUIA individuals, #Enough movement that stands against mass shootings in schools and there is the Black Lives Matter movement, which has grown to become a global network that “builds power to bring justice, healing, and freedom to Black people across the globe.” Among many others, as the leaders and participants of these movements work hard, they are beginning to see legislation passed in favor of these essential causes, slowly. The activists are bravely confronting the choke holds that have been in place to manipulate and exploit life on earth, prevent social progress and sustain violence in the form of police brutality, rape, mass shootings, hate crimes, exploitation and discrimination for far too long.

The murder of George Floyd, in addition to the culmination of so many other Black people who lost their lives at the hands of police officers in the United States, has triggered the largest civil rights movement in history, with all 50 states and more than 18 countries actively participating. The millions of people of all different races and cultures protesting in the global Black Lives Matter movement have called for a defunding of the police in an effort to reduce police budgets and power on a local and state level, and in turn, invest that money directly into poor communities of color through public services. The police force has been a government institution in the United States since 1838, and was founded in order to control slaves and minorities, including indigenous tribes, through implementing “slave patrols and Night Watches. [They] later became modern police departments, both [were] designed to control the behaviors of minorities.” 9. The push to defund the police began “to take a coherent shape in the late ’60s, early ’70s. Initially, the radical edge of this, from the Black Panthers and others, was the idea of community control of the police. But a group of activists and academics wrote a document called The Iron Fist and the Velvet Glove, in which they began to say, ‘Wait a second, is there any policing that’s actually a good idea?’ When we understand the fundamental nature of policing, even if the community has control over it, it’s still a state institution that’s predicated on the use of violence to fix problems. And historically, it has never operated in the interests of the poor and the nonwhite.“ 10In 2019, the police have received around $294 million of the tax revenue, sustaining consistent funding while guts in health care, education, environmental protection and welfare are taking place simultaneously. This was ultimately highlighted by the fact that while states struggled to receive aid during the global Covid-19 health pandemic, police continued to remain funded, and even receiving an increase in funding in an effort to suppress the protests surrounding the murder of George Floyd. Communities of minorities all over the country continue to struggle due to the lack of resources needed to remain healthy, safe and educated, and the presence of police, as they feed the pipeline to the prison system, is only enhancing these disparities. It has been emphasized, with statistical data, that these disparities can better be addressed through adequate access to food, shelter, health care and education, as each of these fundamental resources can lead to a significant reduction in crime in various ways.

In order to sustain the momentum of this movement, it is about collectively adopting a new way of living, seeing and speaking, as well as forcefully and unapologetically making demands and taking back our power in order to assume a new autonomy for ourselves that allows us to live how we want to live. There are practical ways to implement and effect this change, and there are creative and spiritual ways to effect this change, all of which go hand in hand. Protesting raises public awareness and puts a spotlight on injustice, making the establishment in place uncomfortable; history shows that this is one of the only ways that the political system has even paid attention to marginalized communities. Through efforts like the organization of protests, community funds for bailing the protestors out of jail, food banks to support those protesting with sustenance during the protests, it is possible for us to be able to have a voice against the powers in place. But these protests will amount to nothing if our aspirations are not eventually translated into specific laws and institutional practices. When we can elect, or even become, our own government officials, we can respond to the specific needs of our communities. Vote in local and national elections, use your voice in town hall meetings, learn all you can about local political leaders and voting information, pressure the leaders, start your own community watches and community organizations, follow the bills and policies closely and keep protesting if you don’t like what you see happening.

Creatively, cultural semiotics, art and self expression is one of the most powerful tools to have influence and even the most subtle gesture can cause radical change depending on how it becomes infiltrated into the processing library of a culture. For any of those striving to make a realization out of an idea or ideology, language and aesthetics can help to attract support that will carry the message that you want to carry in order to collectively build towards a desired future. This can work for or against one’s favor; a problematic example of this would be semiotics associated with anarchism. For example, it is all too common to understand anarchism as inherently violent, particularly when the colors used are predominantly black and red, and the images often alluding to destruction of property and chaos in the streets. Despite the roots of anarchism being founded in ideas of peace in self government and community organization, the semiotics have made it easy for the governing forces to demonize these ideologies and ultimately equate the idea of self government to a form of chaotic hell where there is no order and no peace. Hypothetically, if today there was an effort to “rebrand” anarchism, what could that look like? What is the imagery of the world anarchism ideally imagines and how can this imagery help to convince others that it is even a world worth considering?

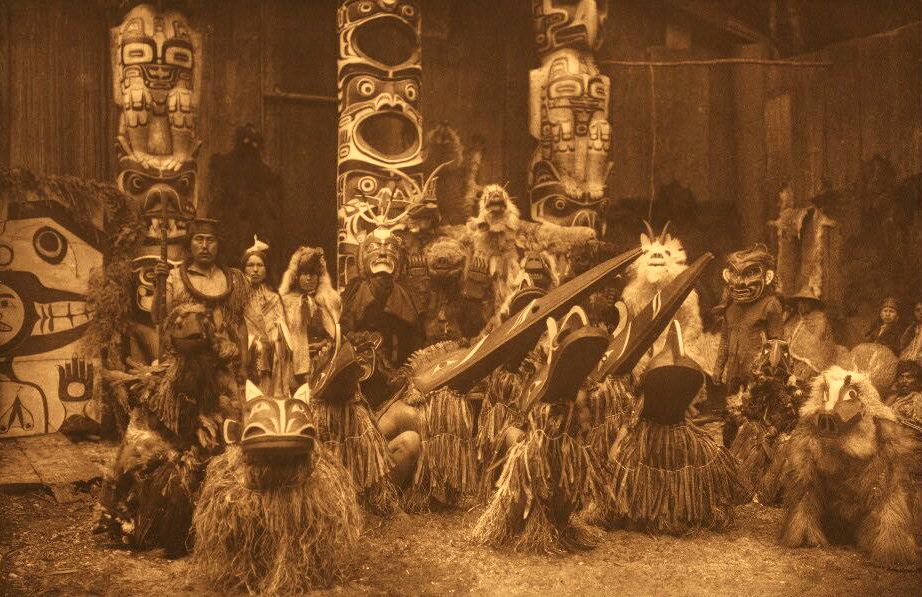

Self expression and art has always held a special place within the Great Divide between the modern and pre-modern, with its enduring investment in the dissolution of borders between fiction, the unconscious mind and objective reality. As mimetic behaviors constituted animistic thought, they were marginalized to the extent of only being recognized as legitimate aspects of modern culture in the cognitive developments of children, in psychosis, and in art. In fact, throughout the 1900’s, the realm of art served as a modern “ghetto” that allowed for the legitimate persistence of mimetic impulses, an emancipation space for the unconscious mind to roam freely. It was in art and art alone that modern civilization had reserved a place where animism was allowed to survive. But the avant garde movements sought to bring about a type of invasion of one reality by another, an intersection of one reality by another, as a way of evoking problems in language that would be needed for rational explanation and understanding. The bringing art back into life of the avant garde was perhaps the first attempt to examine and play, with hopes to reverse the dis-enchantment of the positivist modern structure.

They were able to provoke these boundaries of positivist thought by assuming a position on the periphery, suspending their own taste and even taking on an ambiguous role in society, studying and identifying under various disciplines simultaneously. It was an exercise of ambiguity that infiltrated many areas of society, imagining different ways to function within the existing structures of the modern world. Through objective observation and a subjective understanding of the functions of things and the effects or affects they have on the unconscious mind, they were able to access the middle grounds that were suppressed by the modern world and create manifestations of deterritorialization in both the artist and the viewer that enticed the soul and expose the conditions of it’s oppression. In fact, the term “Degenerate” was used in the various wings of sciences to marginalize those who thought differently, and physicians had all the signs and symptoms to look for, and any deviation from the norm was deemed mad and crazy. But, the creatives of that time confidently announced themselves as outside of the norms of accepted action, statement and belief. They confidently stood outside of the established institutions that enforced the oppression and used their own language, encouraging people to suspend what they know as “truth” in reality in order to open up room to imagine, and even create, a new kind of world.

The spaces in between the pure and “true” entities of our modern structures do exist, they are all that is undefined, they are all that is wild. They are the dreams that we have, the thoughts that flow from one subject to another, they are fluid, they are amorphous, they are free. Are we ready to set forth on a steady pursuit to realize a society that would accommodate for all things, “living” and “nonliving” entities, “human” and “nonhuman” actors, modern and pre modern perspectives? In order to address these unmapping and undisciplining perspectives, it is necessary to create a new narrative, an alternative frame that is at the same time an antiframe. One which can account for the phenomena of life beyond the modernist division. The limiting constraints of modernism has, for a very long time, canceled out any potential for pre modern world views to take influence on the development of culture or modes of communication. Perhaps a newly established direction can form that does seek to slowly and carefully address the constraints that causes modernism to dominate the world, to classify everyone or anything into a constricted definition, and alternatively take up new viewpoints to initiate foundations that could support a broad decolonization of thought.

1. George Kerlin Park, “Animism” Encyclopedia Britannica Online, n.d. Web, 30, January, 2016

2. Research Report, “Native American religious and Cultural Freedom: an Introductory Essay; The Pluralism Project”, Harvard University, Web, 2005

3. Edward B. Tylor, Primitive Culture Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom (London: J. Murray, 1871)

4. Tylor, Primitive Culture Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom

5. Anselm Franke, Animism Vol. I (Berlin: Sternberg, 2010)

6. Franke, Animism Vol. I

7. Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993)

8. Arthur M. Young “Fear of the Unknown” Arthur M. Young: Essays. Anodos Foundation, Web, 1996

9. Dr. Gary Potter “The History of Policing in the United States.” Police Studies Online, Eastern Kentucky University, plsonline.eku.edu/insidelook/history-policing-united-states-part-1984. Accessed 7 June 2020

10. Madison Pauley, “What a World Without Cops Would Look Like”, Mother Jones, 2 June 2020, www.motherjones.com/crime-justice/2020/06/police-abolition-george-floyd/. Accessed 7 June 2020