Leonie Hagen

July 5, 2021

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has turned a lot of peoples’ lives upside down, and in particular, the lives of urbanites. Because of the lock-down, our radius of movement and social circles have been reduced dramatically, with our immediate environment, our neighborhoods and communities, gaining much greater importance. As we have been pushed towards a predominantly local life, our cities have been put on a stress test to prove their livability and their qualities. The poly-centric city, composed of autarchic neighborhoods is a very primal idea of urban habitation in a way, but has been getting more consideration by urban planners and architects around the globe in recent years. Obviously the pandemic has been acting as a catalyst for this trend because many cities have been struggling to provide healthy environments during these challenging times.

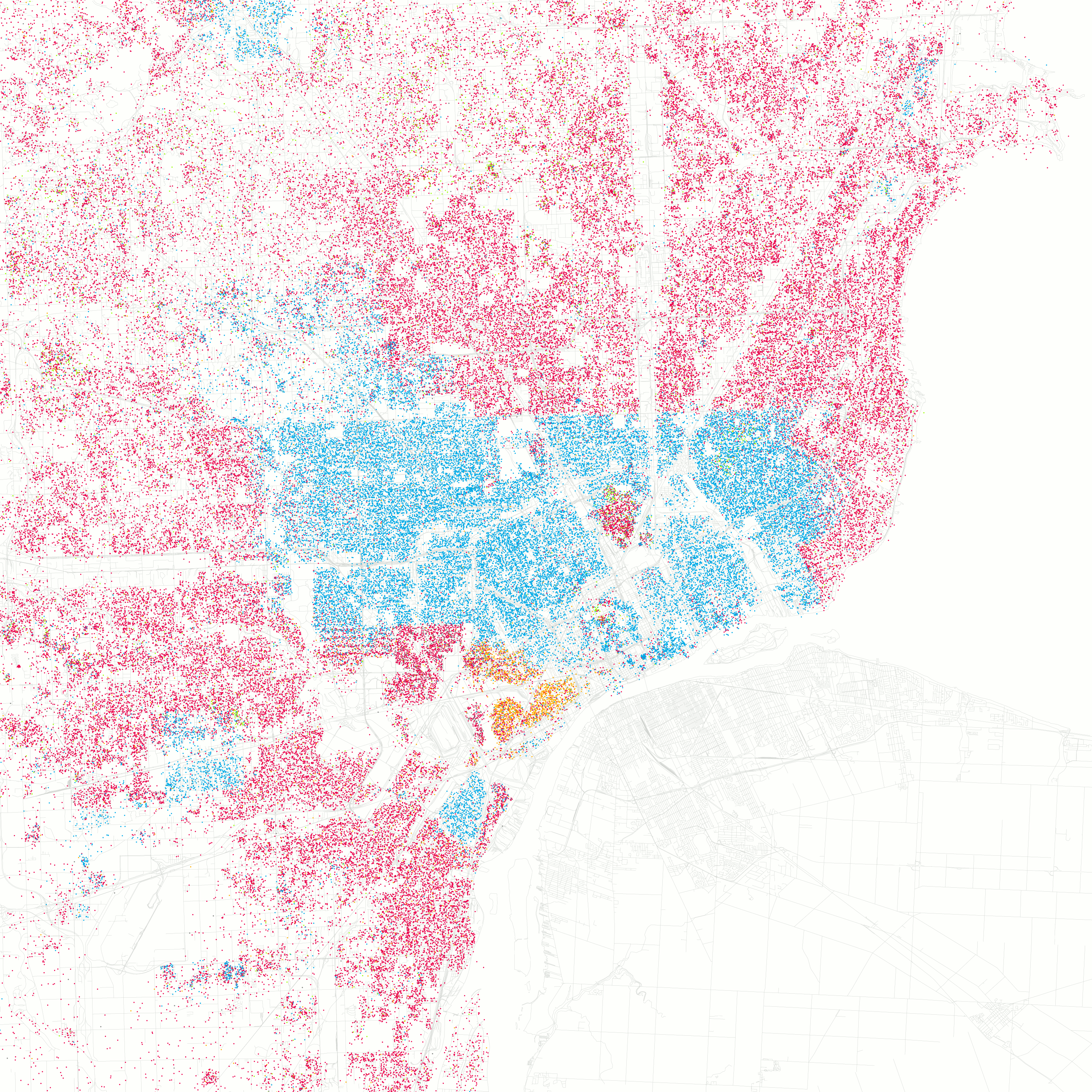

In comparison to other major cities, Detroit seems to offer something numerous city dwellers long for, most notably these days: space. We long for space for ideas, space to unfold and express ourselves, space for opportunities. With about 25% of its city limits vacant, Detroit blatantly stands out in comparison to other urban areas. For that reason Detroit doesn’t read quite like the usual city, it doesn’t have the classical symptoms; it’s not dense, it is sparse. Relatively, it is a thin carpet of habitation. It’s strongest contextual components are vegetal and infrastructural: foliage and roads; it is rather an urban landscape than a city per se.1 It’s monotonous and seemingly endless street-grid labels the fabric “urban”; without this predominant infrastructure, Detroit wouldn’t qualify as a city to the beholder’s eye. The infrastructure superimposes everything.

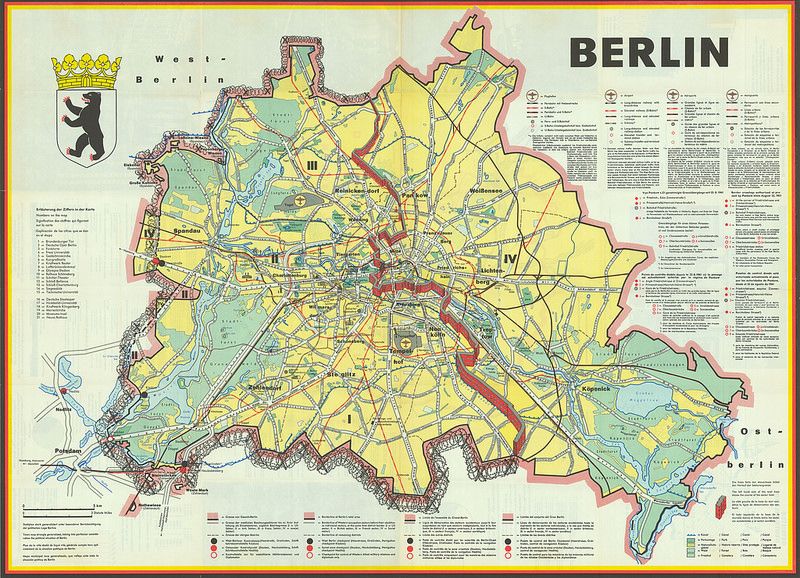

The state of not quite being a regular city is one of the reasons why Detroit has had a somewhat exceptional connection to the German capital of Berlin. This connection is made in spirit also through techno music, underground culture, the arts. Both cities have also been scarred by traumatic socio-political events, hardship and sublime urban developments. From the 60s through to the 80s, Detroit and Berlin were two cities of neglect and were both marked by segregation. After the fall of the famous Berlin wall, Berlin’s re-development slowly took off and left Detroit behind; at that time, not much redevelopment was happening in the Motor City. As Detroit is seemingly slowly recovering, looking back at the development of Berlin might help to understand what could be at stake when imagining Detroit’s future; maybe Berlin can serve as a prediction of how Detroit’s urban landscape might develop if the wrong people are in charge. Just like Berlin a couple of decades ago, Detroit has the quite unique opportunity to redefine what kind of urban environment it wants to be. As Berlin has been through massive changes in the last couple of decades, there seems to be a feeling of nostalgia for the city in the 90s. And Detroit seems to be a reminder of how Berlin used to be in many ways, it seems to capture the spirit that Berlin is holding on to.

As mentioned above, both cities share a history of division, although different political events led up to those divisions – Berlin was physically divided while Detroit’s division was less obvious as the division wasn’t of physical nature, but led up to a similarly divided society through redlining and institutional racism. Both share a history of former glory and subsequent destruction. Both have been through battles of different kinds; Berlin has been heavily destroyed during World War II, Detroit was massively devastated during the Uprising of ‘67 and the city has experienced severe neglect even before and ever since. Both cities have triggered a strong sense of community and togetherness as the people had to come together to rebuild what was destroyed. Both are places of a quite unusual degree of anarchic lawlessness and artistic freedom; one might say that it’s easier to be a freak in Detroit and Berlin than in most other places. Both are hotbeds of electronic music and general artistic creation. Both share a culture of house squatting and inventive low-budget place making. In both cities, people know what it feels like to live amongst ruins and how to make the best of it.

All of the above rather relate Detroit to the Berlin of the 80s and 90s than to today’s city, nonetheless these features are still palpable in Berlin today. The DIY-mindset of Berlin’s past has been carefully preserved and deliberately exploited by investors who are trying to maintain this feeling as the city grows, densifies and gentrifies with no end in sight.

As Berlin was slowly ingested by capitalism and turned into a booming city and a melting pot for people with all kinds of backgrounds, the city is still very attractive to mostly young creatives who want to live in a buzzing, diverse, non-conforming, taboo-free place. But the city has changed tremendously since the fall of the wall; Berlin is back to its pre-war population and it is largely redensified. The fragmentation is still legible in the cityscape but more through weird architectural mix-and-match situations than through land vacancies. What used to be a mecca for artists and free spirits because of space and affordability has turned into a highly competitive market, defined by speculation of anonymous real estate groups and a lack of affordable housing. It’s reunifying and inclusive music scene has become a more and more touristic experience and therefore somewhat exclusive. Berlin has been truly transformed by capitalism, holding on to the spirit of the 90s in an increasingly artificial manner. Gentrification is one of the main terms coming to mind when thinking about Berlin’s urban development. Just from 2008 to 2018, median land prices have quadrupled and there’s no end in sight.2

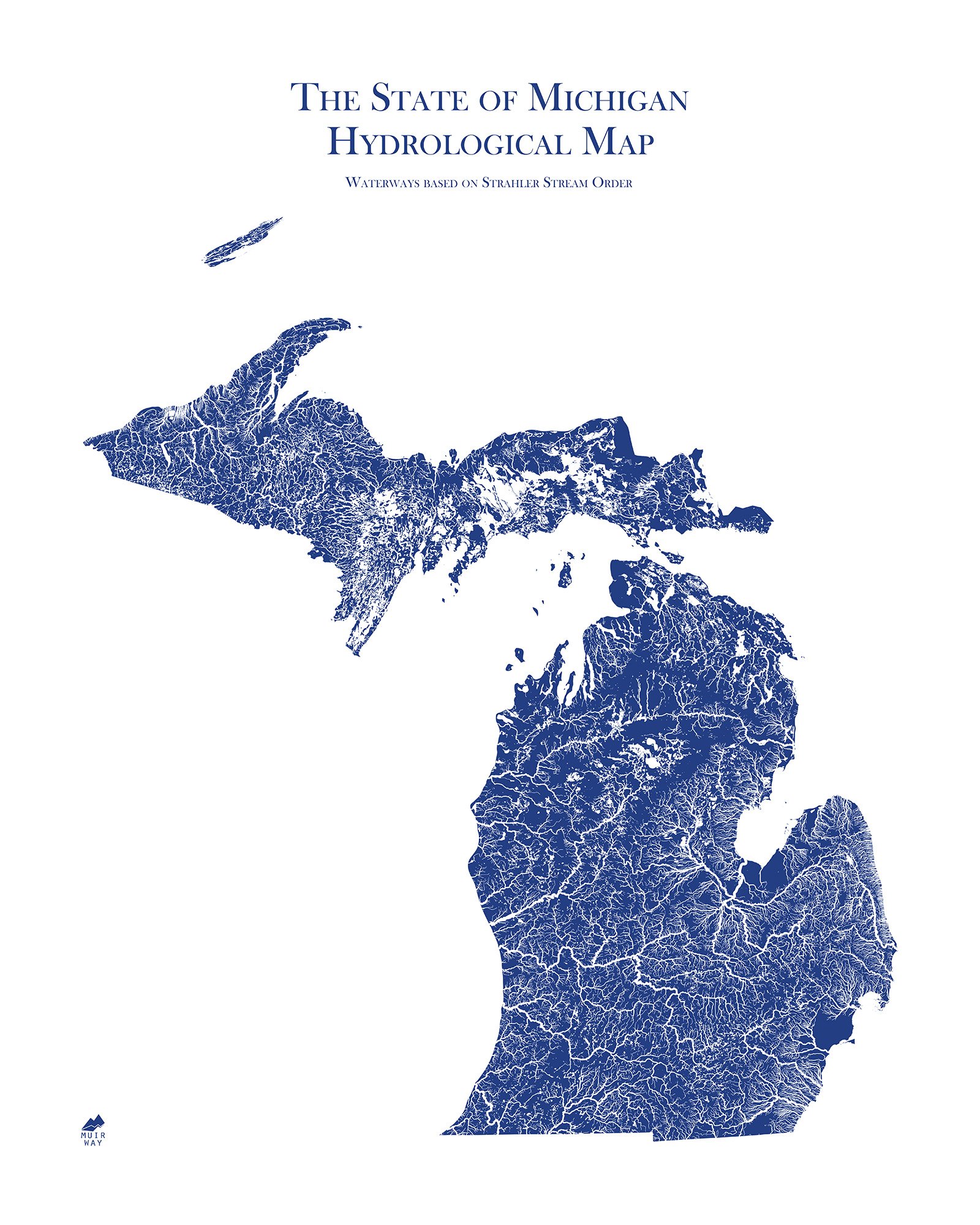

While Detroit’s property and land values are rising more hesitantly, value has been increasing steadily in the last 4 years.3 Of course there is the possibility that Detroit stays affordable and doesn’t pick up speed as fast as Berlin did, but as more and more cities across the US become unaffordable for many and remote work is becoming the new normal, Detroit is gaining attention as an affordable refuge for all sorts of people. Since the city’s crime rates have gone down and much blight has been removed, the city’s perception has changed for the better and turned into an attractive “ruin porn” destination with a “free-spirit” kinda vibe for some, or a possibly lucrative real estate market for others. In a long-term view, with the climate crisis in mind, Michigan furthermore gains attraction due to its outstanding amount of fresh water sources, namely the famous Great Lakes and its uncountable rivers (see fig. 5). While the planet is heating up and natural disasters become more frequent and regularly devastate coastal cities, Michigan seems like a safe haven.

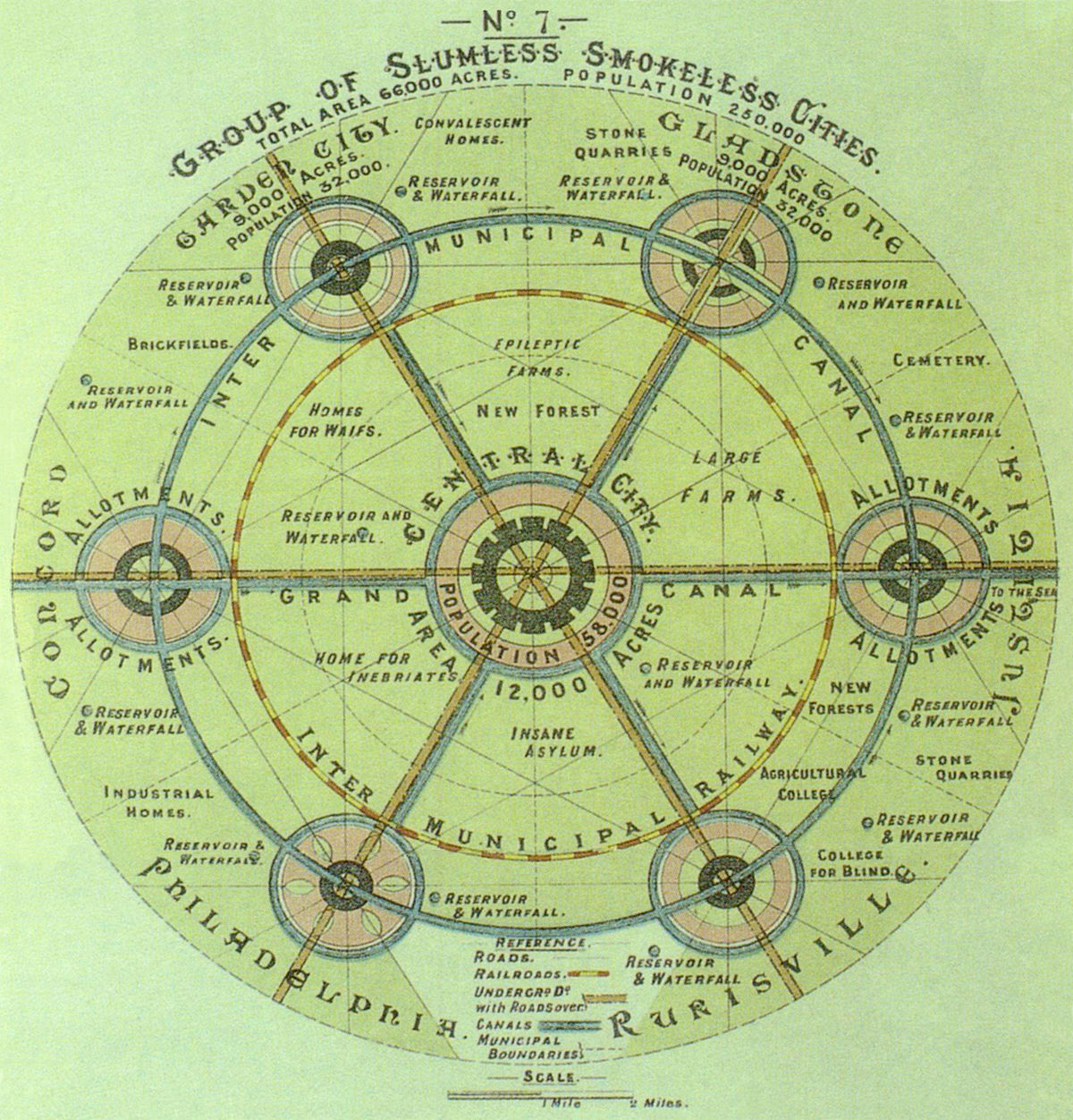

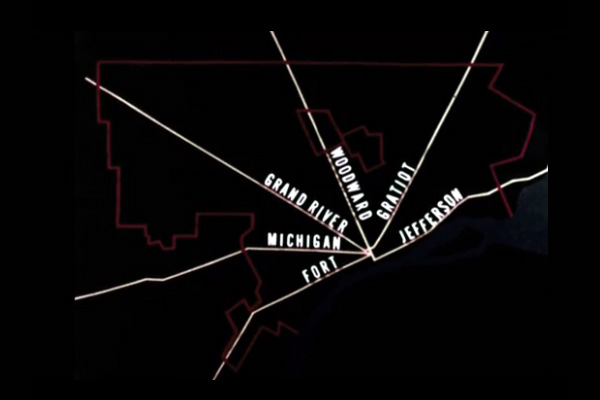

When thinking about what could become of Detroit, there are a few notorious urban planning concepts that come to mind. Inter alia, Detroit’s radial city plan is reminiscent of British Ebenezer Howard’s well-known Garden City idea that originated in the late 19th century. Howard believed that the deterioration and overcrowding of cities was one of the main troubling issues of his time and he aimed to capture the best of both worlds, the countryside and the city, in this urban planning concept of the Garden City (see fig. 6); providing the working class an alternative to either fully remote farm work or overcrowded, unhealthy cities. The ideal Garden City, according to Howard, would be planned on a concentric pattern, connected by six radial boulevards, connecting the satellite towns to the central city. In-between them, generous green belts made up of open spaces and public parks. The satellite cities would be self-contained and composed of housing, industry and agriculture.4

Howard’s urban concept is easily applicable to Detroit. With Downtown as its center, one could imagine densified communities along Detroit’s main infrastructural axes - Fort Street, Michigan Avenue, Grand River Avenue, Woodward Avenue, Gratiot Avenue and Jefferson Avenue - connecting the satellites to the city center (see fig. 7). Of course Ebenezer Howard’s idea was to establish a new ground-up city on vacant, undeveloped land and not to transform an already existing urban fabric, but this idea could still serve as an inspiration. The most interesting aspect of this concept might be the goal to create self-sustained sub-cities or neighborhoods which still have a strong connection to a central city but are not dependent on it. As of today, most neighborhoods in Detroit don’t have immediate access to fresh food, education and cultural facilities; people are forced to drive for miles for these necessities. Kids are often sent off to Charter Schools outside the city and parents drive long distances to get to work. This lack of local services deprives the communities of opportunities to grow and bond.

Another interesting urban concept to consider is the ‘Green Archipelago’ by architects and urban theorists Oswald Mathias Ungers and Rem Koolhaas, which can be seen as an evolution of Ebenezer Howard’s idea (see fig. 8). A less rigid, Post-Modern, city specific approach to redefining urban life in a highly fragmented city. This idea was conceived for the reshaping of Berlin in 1977 and it seems quite easily applicable to Detroit’s current state as well. Due to Berlin’s population loss and it’s damaged building substance, Ungers and Koolhaas proposed to identify significant and identity-establishing ‘islands’ within the existing city while demolishing and renaturating everything in-between those appointed islands. They had in mind a poly-centric city embedded in green, inverting the common city image. A city fabric with green islands, composed of parks, urban forests and fields, becomes a green carpet sprinkled with islands of habitation and industry. According to their idea, the preserved architecture should have subserved as reference for future developments of expanding and densifying those islands.5

When looking at Detroit’s countless vacant lots and it’s prospective future demolitions in the name of the city’s blight removal campaign, this image quite resembles Ungers’ and Koolhaas’ idea. One approach to Detroit’s future could be to invest into the dense neighborhoods, the islands within Detroit’s open space, and make them largely autarchic and self-sustained places and intensely renature the remaining spaces in-between. The autarchic cities of Hamtramck and Highland Park already form dense islands with some social and cultural infrastructure and this could be done on a smaller scale within the city limits of Detroit.

Aiming for a similar goal of self-sustaining small-scale urban areas, the so-called ‘15-minute city’ urban planning concept has gained increasing attention in recent years. Titled by Carlos Moreno, this ideal city structure is made up from a bunch of 15-minute neighborhoods, also called walkable neighborhoods or complete neighborhoods, meaning residents should be able to fulfill most of their essential needs within a 15-minute bike or walk. The concept identifies six essential functions: living, working, commerce, healthcare, education and entertainment. The framework of the model has four components: density, proximity, diversity and digitalization - those components shall be the key to an accessible city with a high quality of urban life.6 This concept yet again pledges for a poly-centric city, which seems to be the only way of sustainable life within cities nowadays.

Looking at Detroit’s neighborhoods, outside of Downtown and maybe Hamtramck and Highland Park, only few essential functions lie within this radius of movement for most of them. Investing into neighborhoods and facilitating them to build a social and cultural framework to accommodate most of those needs locally would not only benefit the city in terms of sustainability and seriously reduce CO2 emissions but it would also allow the communities to thrive and benefit the local economy as people would spend their money in situ.

As Detroit’s economy is slowly recovering and the city is getting more attention from investors, maybe Detroit can learn something from looking at Berlin’s development. As we can see cities around the globe transforming at warp speed, many are becoming less and less livable. Rents are skyrocketing, more and more local long-term residents are getting displaced as a result of it, and finally communities are getting ripped apart. Oftentimes cities lack sufficient high-quality public space and most of all, they’re getting less and less sustainable. Cities have become pools of speculation and investment and evermore don’t meet their resident’s needs.

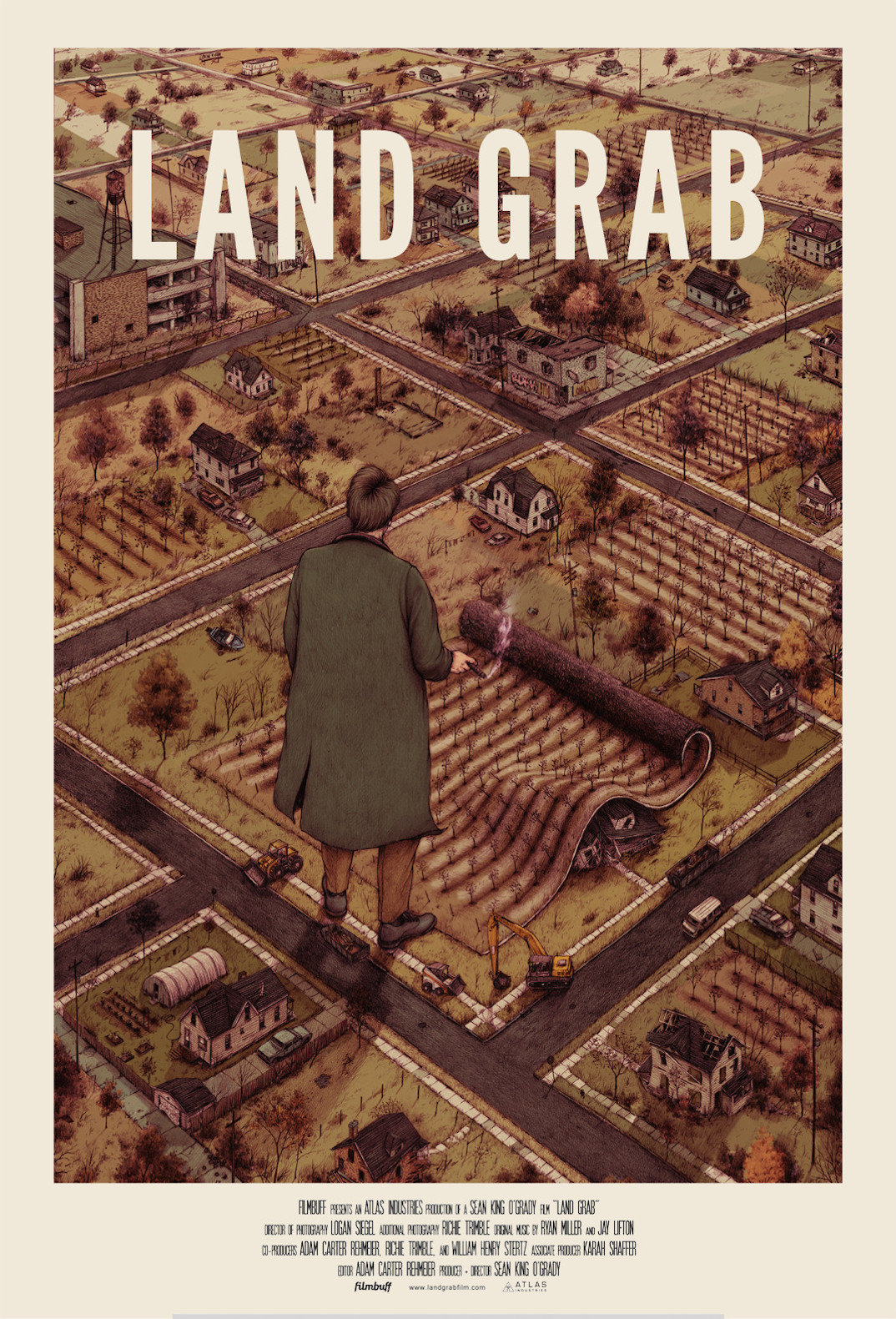

Detroit’s slow recovery and moderate growth appear to be a good thing for the city’s development. It gives the people of Detroit the chance to reflect on changes as they happen, predict things and get involved. A quite unique fact about Detroit is not only that the city has a vast amount of vacant land but also that the biggest chunk of it is in the public’s hand. The Detroit Land Bank has been working towards reducing the amount of land that is in public land in order to stimulate the economy and entice investors without quite understanding or maybe disregarding this unique position and what opportunities publicly owned land could facilitate.

Over the last few decades, the DLB has been selling off large chunks of properties to investment firms which is making some people feel uneasy as this equals a shift of power. People or firms who own a certain amount of land can kick-start change in a neighborhood in no time. And who’s going to stop them? The way the city of Detroit and the DLB are distributing the land doesn’t really give much hope for leadership accountability. Just to name a few, Hantz Group, Quicken Loans, FIRM Real Estate and Prince Concepts each own quite a significant chunk of the city’s land and properties.

In the case of Berlin, from the late 80s through to the 2000s, city officials made an irreversible mistake by selling thousands of former governmentally subsidized low-income housing as well as vacant land to private investors. This sell-off started a massive wave of speculation and led to a tremendous gap in the housing market on the lower end. The end product is that people are displaced and have to move to the city limits or even out of the city. Many people who have been labeled ‘essential’ during the Covid-19 pandemic can’t afford to live in the city anymore and are being ousted. A couple of decades later, the discussion rose to potentially buy land back to develop social housing, which is in dire need. The problem is that the land value has exploded and the city won’t be able to ever again own nearly as much land as it did after the war.

Speculation is starting to happen in Detroit as well, not on the same level and rather punctually but it is happening. Many of Detroit’s residents are happy about new developments as they want to see their city rise from the ashes but in a city with over 30% of its population living below the poverty line, most of the new developments are inaccessible to many.7 Numerous Detroiters agree that the blighted and therefore potentially dangerous structures need to be removed. Blight removal will make neighborhoods more secure and in the long run, property values will rise. But demolition alone won’t remove poverty and joblessness. It doesn’t really seem like any of those programs aim to help the local people but rather to entice newcomers and capital.

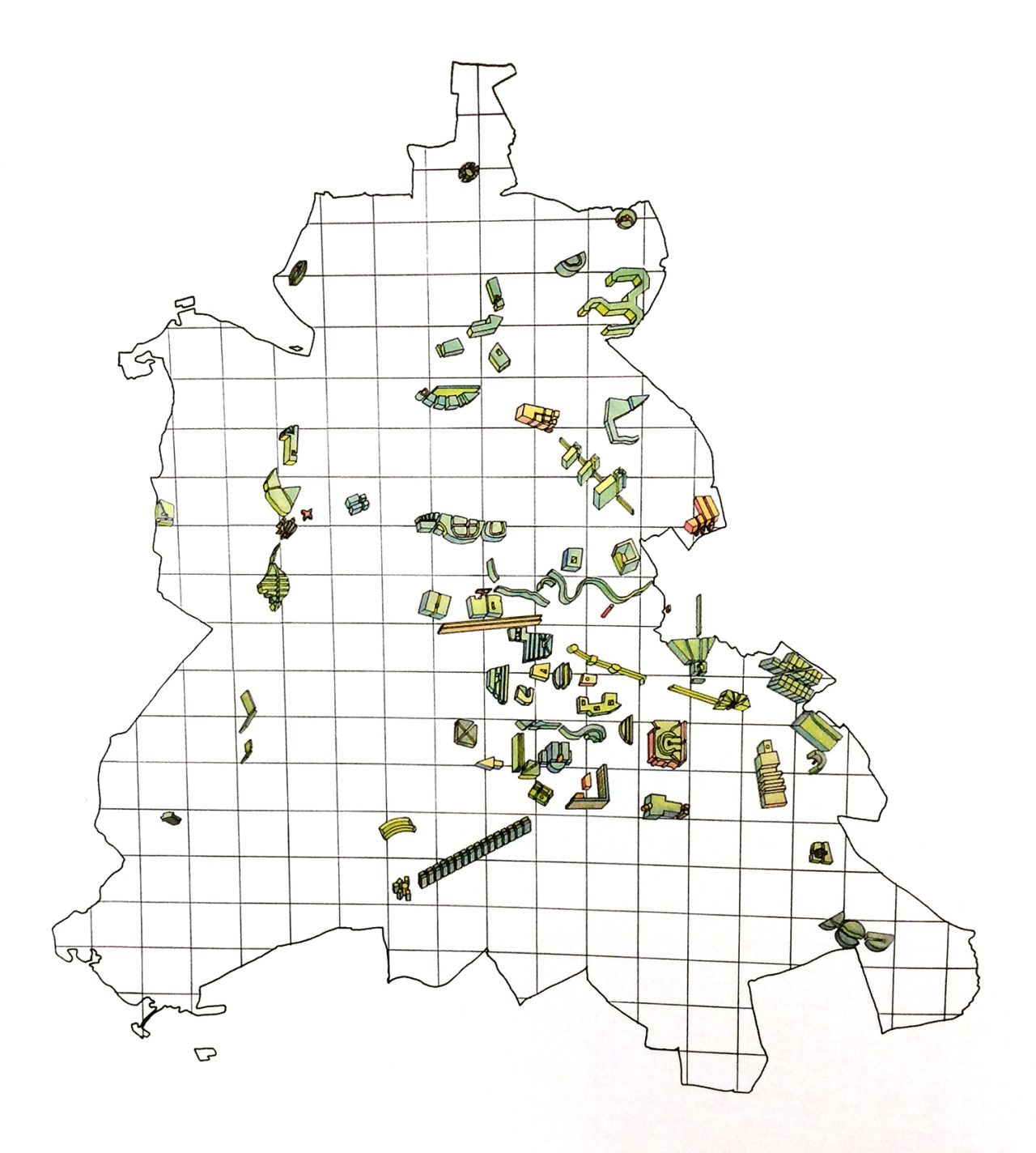

Detroit often times is labeled a food desert. For many neighborhoods, Whole Foods is the closest fresh produce market and it’s simply not affordable to many. As a result of deindustrialization and depopulation, Detroit has faced a massive wave of unemployment and food insecurity. From the 1990s on, locals have found that urban farming is a method to fight food insecurity and poverty, starting after the financial crisis of 2008-09. As a result, in 2018 more than 1,600 gardens were identified within Detroit’s city limits.8 While this culture of urban gardening has brought together communities and strengthened the socio-ecological system, it arose out of a lack of access to fresh and affordable produce. The people of Detroit had to look after themselves when the city wasn’t capable of providing for them.

As a result of, not exclusively but predominantly, extensive urban gardening programs, the value of homes in Detroit’s North End neighborhood for example have tripled since late 2019. “Agricultural neighborhoods bring a different look and feel to the community,” Rondre Brooks, a Detroit Real Estate Agent, says. “While there are the obvious healthy lifestyle benefits, they also create a more appealing environment.”9 This improved and appealing environment of course has its upsides but also bears the future issue of gentrification and unaffordability. Improving neighborhoods has to happen in the interest of those who are already there and not make way for people from elsewhere as its first priority.

It’s a balancing act to allow for sustainable, attractive and healthy urban development and not unleash gentrification at the same time. The city leaders have to make sure that locals don’t get pushed out, the city leaders have to make home-ownership available to residents and subsidized housing for those who can’t afford to own their home. While there might not be a secret recipe for the future development of Detroit, there are a few points which seem non-negotiable to guarantee the well-being of all and to create an inclusive and sustainable city of the future. Let’s define some potential guidelines:

1. A limit to how much land can be in a single person’s or company’s hand has to be introduced in order to prevent large-scale speculation and a ownership monopoly of some sort.

2. Design processes have to be more inclusive of local communities. It must be essential that new developments will nurture the encompassing communities and it must be proven that they benefit from the developments in some way.

3. The city has to make sure that long-term residents of the city have a preemptive right to purchase the buildings they live in before they get sold off and people get evicted.

4. Cultural and educational facilities as well as fresh food stores have to be implemented into the immediate communities, this not only grants healthy employment, shopping and social opportunities to the communities but also is the socially and environmentally sustainable way to live.

5. Demolition is an environmental nightmare; the buildings which can be conserved should be saved by the city and made accessible to low-income locals. New-builds generally have to be avoided, especially in a city with as much abandoned housing as Detroit.

6. Community trust funds should get the priority of rank to buy land in order to avoid speculation and to make sure the needs of locals are met.

One reason why many people from Berlin are attracted to Detroit is because it seems to conserve something that Berlin has lost in large part. They look at Detroit with a feeling of nostalgia for what Berlin had and Detroit still has. Change can happen overwhelmingly fast sometimes and once it has happened, it’s hard to overturn. Lately feels more than ever like a good time to get involved and think about what kind of city environment Detroit could be in the near and far future. It will be unavoidable for Detroit to experience change and there are so many possible directions the city development could steer in, but the people who push for it should be held accountable consistently throughout the process if we want Detroit to remain a special place and become an urban landscape for all.

1. Based on the Essay ‘Atlanta’ in: Koolhaas, R. & Mau, B. (1997). S, M, L, XL. Monacelli Press. p. 833-841

2. Zimmer, E. & Schoenecker, K. (2019). Entwicklung der Grundstücksverkäufe in Berlin und Brandenburg. Zeitschrift Für Amtliche Statistik Berlin Brandenburg, 4, 24–27. Link.

3. Meloni, R. & Kelly, D. (2021, January 22). Property values go up in nearly every Detroit neighborhood. WDIV. Link.

4. Howard, E (1902), Garden Cities of To-morrow (2nd ed.), London: S. Sonnenschein & Co, pp. 2–7.

5. Ungers, O. M. & Koolhaas, R. (2013). The City In The City. Berlin: A Green Archipelago. Lars Müller Publishers.

6. Project website: Link.

7. Oliver, J. (2020, September 17). Detroit No Longer Poorest City In U.S.: Census Data. Detroit, MI Patch. Link.

8. Epifanio, C. (2019, 14. August). Will urban farming save our cities? Perspectives from Detroit and Brussels. LabGov. Link.

9. Adams, B. (2019, November 5). In Detroit, A New Type of Agricultural Neighborhood Has Emerged. YES! Magazine. Link.