Marissa Jezak

July 6, 2020

“Do not become enamored of power.”

-Michel Foucault 1

As artists, we are conditioned to believe that our worth is synonymous with the capital we generate and the admiration we receive. But what power does our work hold, apart from its role in this social exchange? The way art functions not only in a social & political context, but as a tool for healing & self liberation is very relevant in late capitalist society. The exhausting and alienating effects of the economic system we live in tend to be overwhelming, and can cause us to gravitate toward self destruction. When you are imprisoned by an institution, a labor system, a domestic environment, or your own mind, there’s not always a way out. Sometimes you are trapped there awhile and you have to find ways to survive. It becomes clear in the process of displacing pain how art can exist as a means of self-preservation. Through violence/ depression/ isolation/ psychosis/ death, psychic wounds form one on top of the other. Either way, whether it’s lifting us out of pain or going with us further in a downward spiral, art functions as a coping mechanism insofar as its action pacifies suffering.

For centuries, art has been believed to possess healing properties. In Ancient Greece, music and drama were used to lift the spirits of the sick. Throughout the middle ages, music, dance, painting, and literature were utilized as therapeutic tools in cultures around the world. 2 However, the use of art as a tool for self-reflection really took off during the Surrealist movement, alongside the rise in popularity of Sigmund Freud’s theories on dream interpretation and unconscious desires. An introspective approach toward making was born; focusing on the artist’s dreams and unconscious thoughts & desires—a transmutation of spiritual energy. Since the beginning of its development, Surrealism utilized two activities as its main forms of production: automatic drawing & writing, and the written/visual illustration of dreams. 3

In exploring the healing aspect of art, it’s important to note that although Surrealism & art therapy were both heavily influenced by psychoanalytic theory, the two practices differ greatly in their objectives. The specific, controlled environment that art therapy requires is dependent on larger structures in society, & utilizes a therapist-patient relationship. While art therapy ultimately has the goal of relieving clients of their ailments, Surrealism was not interested in treating psychopathology. In fact, Surrealism rejected the institution of psychiatry, despite using the art of psychiatric patients as its inspiration.

In The Surrealist Manifesto, Andrè Breton defined Surrealism as:

n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern. 4

Mental illness was frequently romanticized by the Surrealists; for example in Andrè Breton’s Nadja. 5 The stereotype “insane = genius” was idealized in Surrealist art, as illustrated in the wide exploitation of psychiatric patients’ art by doctors, patrons, and other artists. 6 However problematic in its methods, Surrealism’s most important achievement was that it gave validity to the language of the “insane”.

Modern medicine always wants to suppress psychosis, and ignores the beauty in sadness, but there is something powerful there—in the language, to be embraced.

“Having abandoned the strenuous attempt to reconcile himself to the demands and sacrifices of day-to-day existence in the world, the psychotic withdraws into the utter isolation of the self. Within that altered state of consciousness, for reasons that we understand no better than we understand any creativity, the psychotic begins to form images that, paradoxically, may be aimed, in part, at reestablishing contact with the outer world. The artist and the madman seem intent on building a bridge, each from his own standpoint, in the world or out of it, erecting a structure between the self and other, between the world and the mind, between the surface and the depth.” 7

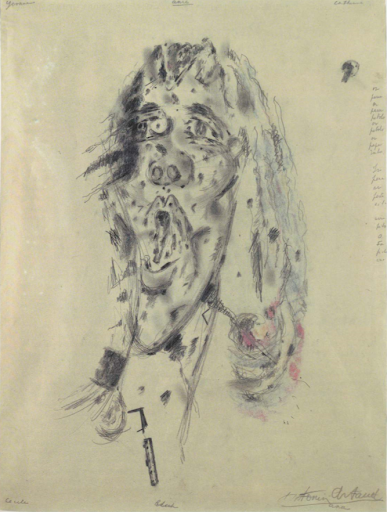

Best known for conceptualizing the Theatre of Cruelty, Antonin Artaud was a vital force in revolutionizing contemporary theatre, literature, and art. Artaud was briefly associated with the early Surrealist movement, but was expelled by Breton & went on to achieve many artistic accomplishments in his own right. His writing is incomparable to anything preceding it—an elaborate, visceral image of cannibalism, erotic fantasy, and psychotic revelation. He spent nearly a decade in psychiatric hospitals between 1937-1948. During this period, Artaud was subject to electroshock therapy multiple times & reported having an out-of-body-experience.

Artaud identified very strongly with Vincent Van Gogh, and in a review of his work, wrote that Van Gogh was “suicided by society”; he believed that the madman is not sick, but rather that he is a victim of a sick society. He criticized the psychiatric system, and expressed hope for a world that would reassess its techniques for the classification & treatment of mental illness—a world more inclusive of people like him. During his long confinement in the hospital, Artaud never stopped communicating with the outside world, as documented in the profound letters, writings, and drawings he left behind. Artaud’s visual & written works reveal a tortured psyche that has fully broken away from a normal perception of reality and is coagulating in a new tongue. 8

“scraped on its own

urine,

latrines of a bony death,

always screw-cut by the same

dismal

vigor,

The same fire,

whose cave

innovator of a terrible

nucleus,

placed in the enclosure

of mother life,

is the viper

of my eggs.

For it is the end which is the beginning.

And this end

is the very one

that eliminates

all means.

And now,

all of you, beings,

I have to tell you that you have always made me shit.

Go form

a swarm

of the pussy

of infestation,

crab lice

of eternity.

Never again shall I meet beings who swallow the nail of life.” 9

.png)

“The marvelous logic of the mad which seems to mock that of the logicians because it resembles it so exactly, or rather because at the secret heart of madness, at the core of so many errors, so many absurdities, so many words and gestures without consequence, we discover, finally, the hidden perfection of a language [...] The ultimate language of madness is that of reason”. 10

_900.jpg)

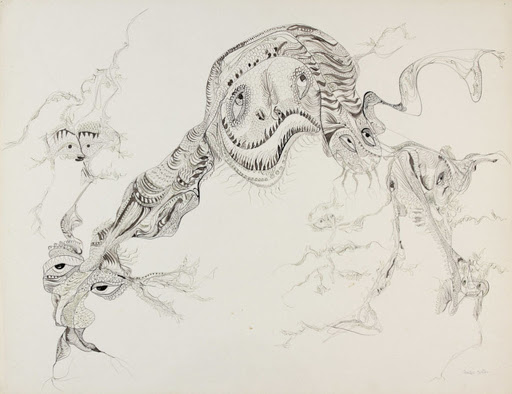

Another artist/writer historically related to the Surrealist movement was Unica Zürn, who composed brilliant works of fiction such as Dark Spring and The Man of Jasmine. Her powerful writing & drawings of biomorphic creatures present an elegant perspective on a disturbed reality; giving semi-autobiographical accounts of her experiences with sex, abortion, violence, love, and mental illness. Zürn’s personal traumas greatly informed her work, and also caused her intense suffering, as she was hospitalized many times throughout her life. In 1970 she tragically killed herself by jumping out of a window to her death. 11

In her anagrams, Zürn dissected texts and then rearranged them to create entirely new sentences with new meanings. Zürn’s partner Hans Bellmer described her anagrammatic poetry in her book Hexentexte as follows:

“What is at stake here is a totally new unity of form, meaning and feeling: language-images that cannot simply be thought up or written up. They enter suddenly and for real into their interconnections, radiating multiple meanings, meandering loops lassoing neighboring sense and sound. They constitute new, multi faceted objects, resembling poly planes made of mirrors. “Beil” (hatchet) becomes “Lieb’” (Love) and “Leib” (body), when the hurried stonehand glides over it; the wonder of it lifts us up and rides away with us on its broomstick. The process remains enigmatic. For this kind of imaging and composing to happen, no doubt an eager hobgoblin—oracularly, sometimes spectacularly—adds much of its own behind the back of the I. A pleasantly disrespectful spirit, in all probability, who is serious only about singing the praises of the improbable, of error and of chance. As if the illogical was relaxation, as if laughter was permitted while thinking, as if error was a way and chance a proof of eternity.” 12

Zürn writes:

AND IF THEY HAVE NOT DIED

I am yours, otherwise it escapes and

wipes us into death. Sing, burn

Sun, don’t die, sing, turn and

born, to turn and into Nothing is

never. The gone creates sense - or

not died have they and when

and when dead - they are not.

WILL I MEET YOU SOMETIME?

After three ways in the rain image

when waking your counterimage: he,

the magician. Angels weave you in

the dragonbody. Rings in the way,

long in the rain I become yours. 13

To an extent the anagram can be seen as an analogy to what happens when new language is formed after trauma; psychic content is reconfigured into new compositions, and the elements of memory are transmuted into an altered state. Julia Kristeva writes that the manic, in compensating for the narcissistic wound, “builds a shield against loss” and that, “the work of art that insures the rebirth of its author and its reader or viewer is one that succeeds in integrating the artificial language it puts forward (new style, new composition, surprising imagination) and the unnamed agitations of an omnipotent self that ordinary social and linguistic usage always leave somewhat orphaned or plunged into mourning. Hence such a fiction, if it isn’t an antidepressant, is at least a survival, a resurrection…” 14

The omnipotent self Kristeva refers to here is expressed in preverbal semiotics—motor, gestural, olfactory, vocal, auditory, tactile (primary processes). Power resides in these semiotic rhythms, which illustrate a strong presence of meaning within a presubject that is not yet capable of signification. Originating in psychoanalysis, the idea of omnipotence mirrors the disturbance of the psychotic, and can be used as a tool to help better understand the mechanics of artists like Antonin Artaud & Unica Zürn. 15

In nursing the wounds caused by traumatic events, what happens in the overlap of suffering and healing is potent. Unfortunately, in a culture that constantly demands efficiency, there is rarely enough time for reflection & care of the self. Living in a perpetual cognitive dissonance, serving those who exploit us in a struggle for survival... In the course of life we become vulnerable to violence on all sides. We lose our direction.

Constantly, we’re taken advantage of by the same structures & people that claim to be helping us. The safety net we pretended to believe in is dissolving, and now we’re in the molting period. It’s from this point that we must make adjustments toward self-sustainability. With the purpose of maintaining homeostasis, how can we reimagine art as a grounding mechanism in a dissociative space? If the end game is to survive & find contentment in that survival, what actions could be put into place to help catalyze this change? Is there a future-space for radical, experimental art practices based around healing?

1 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: Preface by Michel Foucault, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (London: The Athlone Press, 1984), xiv.

2 Gladding, Samuel T. The Creative Arts in Counseling. 4th ed. (Alexandria: American Counseling Association, 2011).

3 MacGregor, John M., The Discovery of the Art of the Insane (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 270-91.

4 Breton, André, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1969), 26.

5 Nadja (1928) is a semi-autobiographical story of a brief love affair/obsession with a female psychiatric patient. The narrator remains fully absorbed by Nadja’s mystifying aura long after their separation; it is in her absence that she roots even deeper into his unconscious.

6 see note 3 above.

7 Ibid.

8 Barber, Stephen. Artaud: The Screaming Body (New York: The Tears Corporation/Creation, 1999), 48-60.

9 Artaud, Antonin. “Indian Culture and Here Lies.” Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings, edited by Susan Sontag, University of California Press, 1976, 544.

10 Foucault, Michel, Madness and Civilization, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Random House, Inc., 1965), 95

11 Zürn, Unica, The Man of Jasmine (London: Atlas Press, 1977).

12 “Unica Zürn: Nine Anagrammatic Poems,” Poems and Poetics, July 31st, 2009, http://poemsandpoetics.blogspot.com/2009/07/unica-zurn-nine-anagrammatic-poems.html.

13 Ibid.

14 Kristeva, Julia, Black Sun:Depression and Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), 50-51.

15 Kristeva, Julia, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), 61-62. On omnipotence: “The study of very young children, and also the dynamics of psychosis, leads one to conjecture that the most archaic psychic processes are the projections of the good and bad components of a not-yet self onto an object not yet separated from it, with the aim less of attacking the other than of gaining a hold over it, an omnipotent possession. Such oral and anal omnipotence is perhaps the more intense as certain biopsychological particularities hamper the ideally wished for autonomy of the self (psychomotor difficulties, auditory or visual disorders, various illnesses, etc.). The behavior of mothers and fathers, overprotective and uneasy, who have chosen the child as a narcissistic artificial limb and keep incorporating that child as a restoring element for the adult psyche intensifies the infant’s tendency toward omnipotence.”