Ashley Cook

June 4, 2024

Detroit has seen over 20,000 commercial buildings and homes demolished since April 2014 as a result of the Detroit Demolition Program, a “rapid and targeted” initiative formed by Mayor Mike Duggan as part of Michigan’s larger Blight Elimination Program.1 Over the past decade, city residents have witnessed these newly vacant lots grow rich with foliage and become home to a variety of wildlife. Needless to say, the air is cleaner, the city is greener, and people are inspired. The “neighborhood stabilization”2 efforts happening throughout the city have incorporated not only the removal of condemned properties, but also the rehabilitation of others, in an effort to bring new life to the area. Library Street Collective is just one of the creative groups in Detroit that is imagining a future for the city and introducing infrastructure to support their vision. Anthony and JJ Curis are the founders of Library Street Collective, a Detroit-based art gallery that has been active since 2012. They opened a second gallery, Louis Buhl & Co., in 2017, and this year, are further expanding their mission to present Detroit artists to a global market through a project called Little Village, a collection of creative spaces spanning a few city blocks on Detroit’s east side.

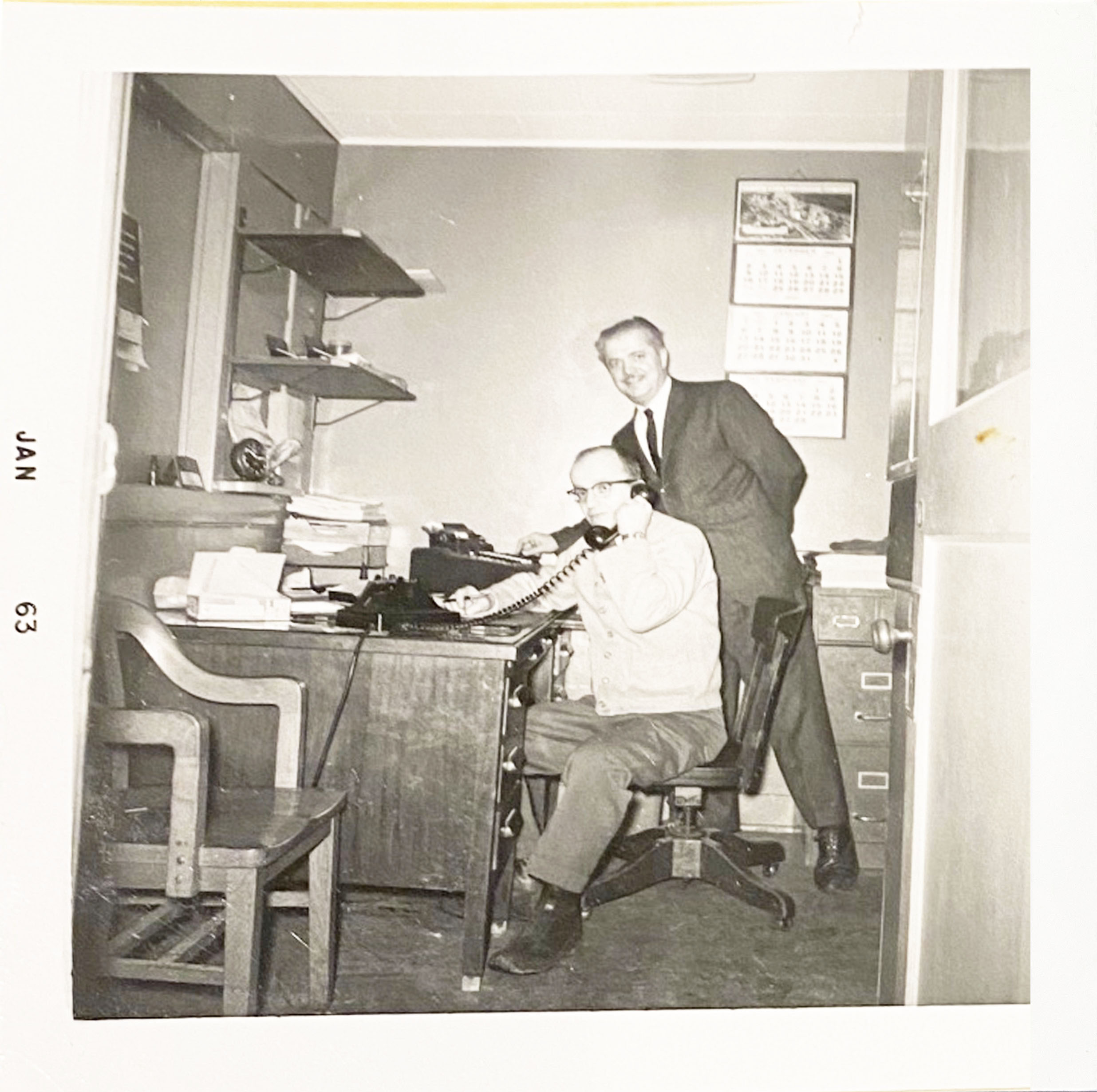

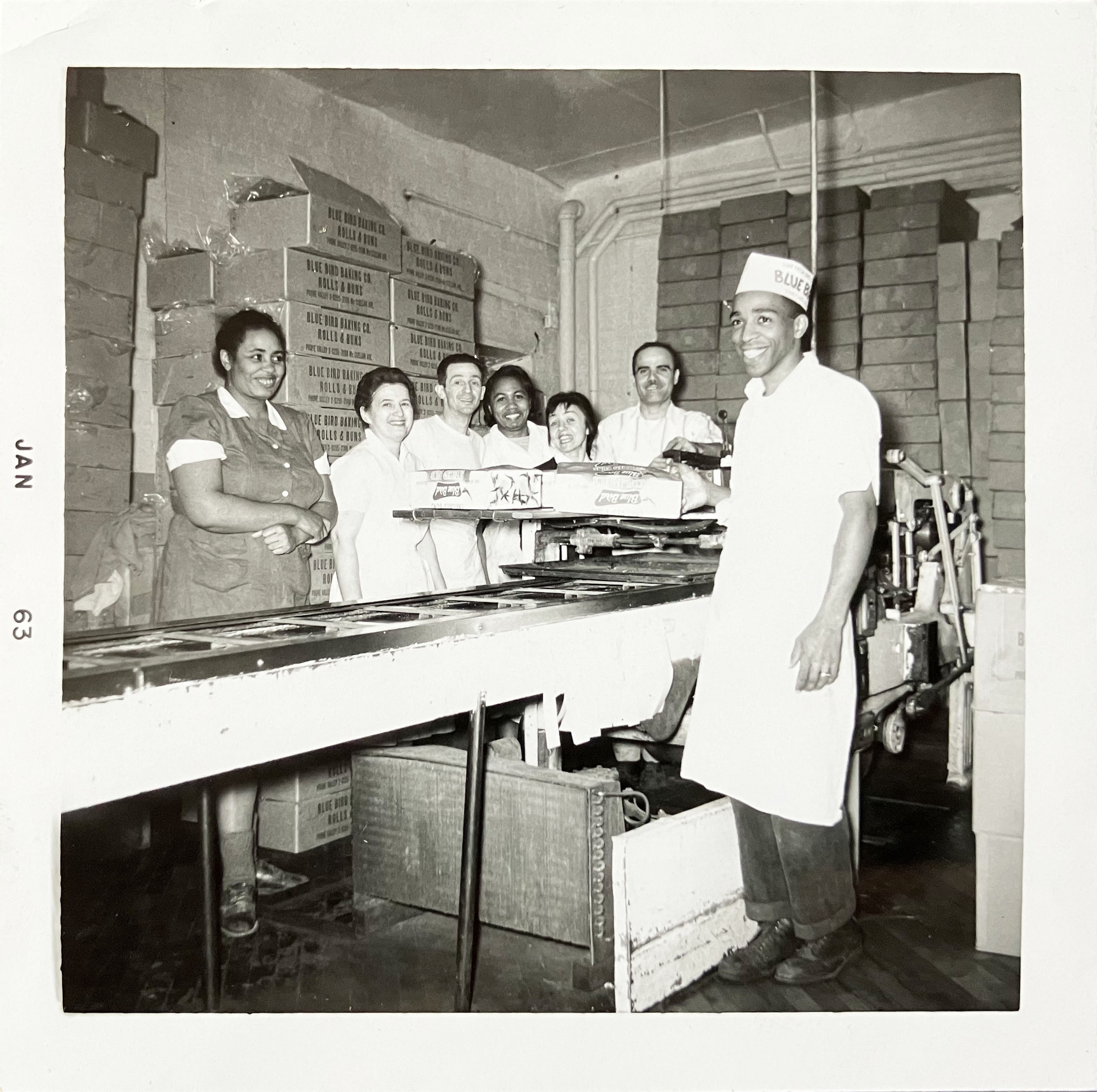

Property restoration in East Village is the focal point for this project, with each of the locations having historically hosted businesses and institutions that were at one time staples of their community, but have since succumbed to challenges brought about by the city’s rocky history. Little Village’s LANTERN at 9301 Kercheval was one of the homes of Blue Bird Baking Company, a family business owned by cousins John Cardasis and Peter Bogas who immigrated as children to Detroit from Northern Epirus, Greece. The origin of their story provides a glimpse into a time when Detroit was rising to the top as an industrial powerhouse. It was John’s father, Constantine Cardasis who introduced the family to this industry, working as an employee of Blue Bird Baking Co. after arriving in the United States in the 1930s, at the tail end of the mass immigration of Europeans to the United States.3 After serving in World War II, John Cardasis and Peter Bogas returned home and purchased Blue Bird Baking Co. in 1946. As Greek Americans, they contributed to the multiculturalism of the US, bringing their international perspective and dedicated work ethic to Detroit. Blue Bird Baking Company’s reputation steadily grew as they served local and national businesses for over fifty years, including Detroit Public Schools, Burger King, Wonder Bread, Taystee, local supermarkets, bars, and many Coney Islands that were owned by Greek and Albanian families. The family remarks that “running Blue Bird Baking Co. was a lot of hard work and dedication. The employees were very diverse throughout all of our years in operation and it felt like family to everyone who worked there.”4

As the family reflects on their firsthand experience as business owners throughout the city’s most vibrant years, and also the most turbulent years, they recognize the community as a factor in their success and longevity. “We believe that because the business was so deep rooted into the community, that is what helped us get through tough times. For instance, during the riots of 1967, people came in and looked around, but, thankfully, left the bakery untouched. In the 1970’s, the neighborhood was family oriented, with many local churches in the neighborhood, including one right across the street. But in the 80’s, properties started deteriorating and because of this, we needed to move to the location in Highland Park. We stayed there until we sold the business in 1999.”5

9301 Kercheval sat empty and neglected until it was acquired by the Curises in September 2021. Their conscious decision to rehabilitate the existing property led them to connect with Jason Long, a partner of the international architectural practice OMA, who has worked with methods of adaptive reuse and preservation in many of his previous architectural endeavors. The process of transforming an old space from one use to another requires a comprehensive approach that involves a knowledge of construction techniques throughout history, an acute exploration of the site’s sustained qualities, and a curiosity to welcome unconventional solutions that can provide for the needs of the new venture. I was lucky to have the opportunity to discuss this project with Jason Long and his team members, Sam Biroscak and Sophia Choi, where they revealed some of the challenges and potentials inherent in the act of urban revival. They explain the thought processes that went into transforming the 80 year old bread factory into a space for the creative nonprofits Signal-Return and Progressive Art Studio Collective (PASC), who are now residents of LANTERN.

Ashley Cook: Jason, Sam, and Sophia. It is great to talk with you about the process of transforming this building. Could you explain some of the thoughts you had when going into this project?

Jason Long: When planning the overall layout of LANTERN, we wanted to create a kind of “factory” where the production of PASC and Signal-Return would take place. We also wanted to make space for the artists to showcase their work. While LANTERN was created to offer studio space for these nonprofits, LSC also wanted to incorporate space for the public, so the floor plan also allows for commercial businesses, a cafe, and a market. With a distinct focus on community-building, the courtyard was conceived as a central outdoor space, providing entries to the various tenants on the ground floor and a gathering space for different activities. In addition to providing a lot of room to congregate, the depth of the courtyard was convenient for us as it allowed for a ramp with a gradual incline to make all spaces are easily accessible to everyone.

Sam Biroscak: We recognized the quality of the space as soon as we saw it, even in the state that it was in. There were a lot of structurally strong elements, and interesting architectural details to play with, like a loading dock and a winch where trucks would come in and unload materials. This area is in the Southeast corner where the cafe will soon be. Because of this aspects specifically, the height from floor to ceiling in this area goes up to 26 feet. Embracing existing details to create something unexpected for the public is a big part of the pleasure of this project.

JL: The first of the three buildings was built in 1924, then expanded twice over the years. The North building was previously two stories, but the floor of the second story was gone when we arrived. The middle building had a roof and was just one story, and the South building had no roof. Where the building was missing its roof, we preserved the joists that remained, which now hover above the communal courtyard and can provide infrastructure for future activations, such as hanging installations, lighting, or a canopy. When planning to replace the roof over the area west of the courtyard, which will soon be the space for a bar called Collect Beer, we wanted to visually imply the motion of taking what would have been the roof of the building and folding it inwards, resulting in the accordian-like sawtooth roof that is here now. The building had an expansive, bland facade made of concrete masonry. At first, we were not quite sure how to approach its blankness. One thing we did know is that we wanted to bring light in. We tried creating larger openings found on the North building, and also tried making them weird and funky shapes to contrast with the original windows, but neither approach felt right. Eventually, we liked the monolithic expanse of the existing wall, and the way to preserve that quality while still bringing light in was to drill holes into the wall. We knew it was a crazy idea, but were lucky to work with Anthony and JJ, who had faith and took the leap. After careful planning, we hired a local team to drill around 1,350 holes into the wall. CIR Group (the contractor) was great and figured out how to make it work. The holes spanning the wall allow the light to shine through. They are inset with industrial-use glass bullets that are originally designed for sidewalks. The light inside changes throughout the day based on the natural lighting outside, but at night, the glow comes from inside, viewable outside, like a lantern.

SB: In this case, it was difficult to predict how the light would behave, particularly with these small holes in the walls. We were happy with the results, but this is probably the first and last time we will do something like this. There is something about Detroit that allows for these kinds of details to happen. It would not be possible in other cities because of regulation reasons, or because it may be impossible to find a builder to do it. It is also a credit to the Curises for being open-minded and dedicated to the concept from the beginning.

AC: I feel like I have seen similar exploratory approaches to architecture happening in Europe, and it is refreshing to have them happening in Detroit. I am wondering if all the architects who worked on this project are American, or if they are from overseas?

JL: Sophia Choi, Sam Biroscak and I are all American, but OMA is an international office. We have three offices. One in Rotterdam, where the office was founded, one in New York, and one in Hong Kong. We have two partners in New York, and one of them is Japanese, so from the New York office, we also work on the projects happening in Japan. OMA was founded in 1975 in Rotterdam, but they expanded to New York in 2006 because we were starting to have many projects in the U.S.

AC: Have you ever done any projects in Detroit before? I noticed that you have worked on a lot of projects that focus on the regeneration of old properties.

JL: No, this is my first project in Detroit. It has been great! There is really a wave of projects here that are about using existing structures, ranging from skyscrapers to gigantic factories, down to these smaller spaces like what we are working with for LANTERN. It has been compelling both creatively and economically, to make something like this happen.

AC: I always think it is so meaningful to figure out how to keep these buildings standing, even if the previous business is no longer there. For instance, this was a family-owned bread factory, and there are people in the neighborhood who have been here for generations who have known about this business. They now get to see it being reinvented as opposed to being knocked down and erased.

JL: You know, when I first joined the office, we were looking at a project that involved preservation in Beijing. At that time, Beijing was going through this incredible wave of new development, and we witnessed so many old spaces being wiped away and in turn, creating a complete memory loss. I also think that there is a real benefit to working with older buildings, because of the solidity that they have. Buildings were so often generous and robustly built back then, and this is something that is harder to come by with newer constructions.

AC: What are some of the most interesting and challenging aspects of working on projects that involve reviving old buildings for a new purpose?

JL: It can sometimes be difficult to find a balance. We always try to play off what is there and add new elements without having a jarring contrast. I think it’s important to be clear about what is old and what is new, in order to avoid re-doing what was done before while facilitating a new life for the building. Riding that balance between complimenting without copying or clashing can be learned from experiences like this, but that balance also varies from project to project.

AC: So, this is part of a bigger project called Little Village. Can you talk a bit about that?

JL: Little Village is a community project by Library Street Collective located in East Village. It incorporates different creative spaces including the Shepherd , which is an old rectory that has been re-purposed into an art gallery. Across the street from the Shepherd will be a new space for Louis Buhl & Co., and in the lot next door, there is the Charles McGee Legacy Park. Library Street Collective also purchased a marina, which will become a Little Village space as well.6

To learn more about LANTERN and Little Village,

visit https://lscgallery.com/east-village

To learn more about OMA,

visit https://www.oma.com/

1. Brandon Peterson “Demolition Space and Housing Removal Policy in Detroit.” DSpace@MIT, 2018. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/118239.

2. Ibid.

3. Ari. “A Timeline of Greek Immigration to America.” Diaspora Travel Greece,

March 27, 2020. https://diasporatravelgreece.com/a-timeline-of-greek-immigration-to-america

4. Anthony Tocco and Family, Interview exchange of questions and answers via email, April 28, 2024.

5. Ibid.

6. Jason Long, Sophia Choi and Samuel Biroscak, In person conversation, April 8, 2024