Marissa Jezak

April 3, 2023

The need for play is an active urge that manifests itself in physical movement—it is the most basic indicator of animal vitality. Play can be understood as any activity that fulfills no purpose except to entertain, pass the time, or purely for enjoyment. It is a key component of life for the child, and slowly fades from one’s behavior as they grow older and begin replacing play with work, subordinating their actions to purpose. The expressive gestures which make up play are flexible—they can be adapted to any setting, from raw materials to complex games to nothing except the imagination. Around the world, it has become normal practice to build structures specifically for children in order to satisfy this active urge—the urge to play. The development of these “playscapes” or “playgrounds” is ongoing as they continually change to fit the needs of the modern child, and stretch the capabilities of design and technology. Following is a brief overview of the different architectural styles used in the design of playgrounds since their emergence, and the environmental factors that influenced this evolution.

Just earlier this year a playground was unveiled in Melbourne, Australia with an unusual aesthetic. Rather than simple swings or a merry-go-round, giant boulders form the main component of the space, designed by Mike Hewson. Slides, nets, and monkey bars are sandwiched between the rocks, but there are no handrails or platforms anywhere—this architectural choice is meant to encourage “risk-play”, a more explorative, intuition-based play style. While blatantly lacking resemblance to common children’s playscapes of our time, the installation emulates a natural landscape, and presents more challenging and confidence-building problems to those whom interact with it.1 Its design success is illustrated through its variously scaled components (made to accommodate all ages), multifunctional interactive sculptures, and activation of the city center. Not only is it a tool for exercise, but more importantly it serves as a focal point for socialization.

Comparatively, back in the day, playgrounds tended to emphasize athletic performance by incorporating gymnastics equipment as well as colossal climbing objects like poles, ropes, and ladders. While certainly providing an adrenaline rush—and probably a few concussions, this type of design doesn’t allow much space for creativity. Instead, it is made to function more like a traditional gymnasium, or a military obstacle course, with many single-function objects that require children to maintain a rigid, orderly pattern to their playtime. Metal and wood made up the primary materials of these olden structures, and often they had hard dirt floors. In the early 1900s, this style was quite normal as the concept of designated play areas for children in the city was still being established. (In pre-industrial times, it was not uncommon for youth to independently explore throughout the city, making their own “playgrounds”. Only after the revolutionary expansion of factories/workplaces and car traffic did it become necessary to delegate specific space to play.2) Over time, architects and urban planners dialed in on various aspects to perfect the playground and make it better suited to a realistic idea of a growing child’s needs and desires.

Notable in this growth were the contributions of Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, whose groundbreaking Structuralist designs breathed new life back into vacant spaces throughout Amsterdam in the mid 20th century. Following the post WWII baby boom, urban planning initiatives were set into action to accommodate the growing population–this included designing special areas where children could go to play, apart from the high-traffic of the industrialized city. Ideas prioritizing the element of play and allowing individuality in youth were circulating among the social sciences and different cultural fields at the time, for example in Johan Huizinga’s book Homo Ludens. van Eyck was highly influenced by these philosophies in his work, designing over seven hundred public playgrounds in the city, containing innovative elements that would go on to be reproduced by other designers all over the world, such as the “igloo”, a dome-shaped climbing frame.3

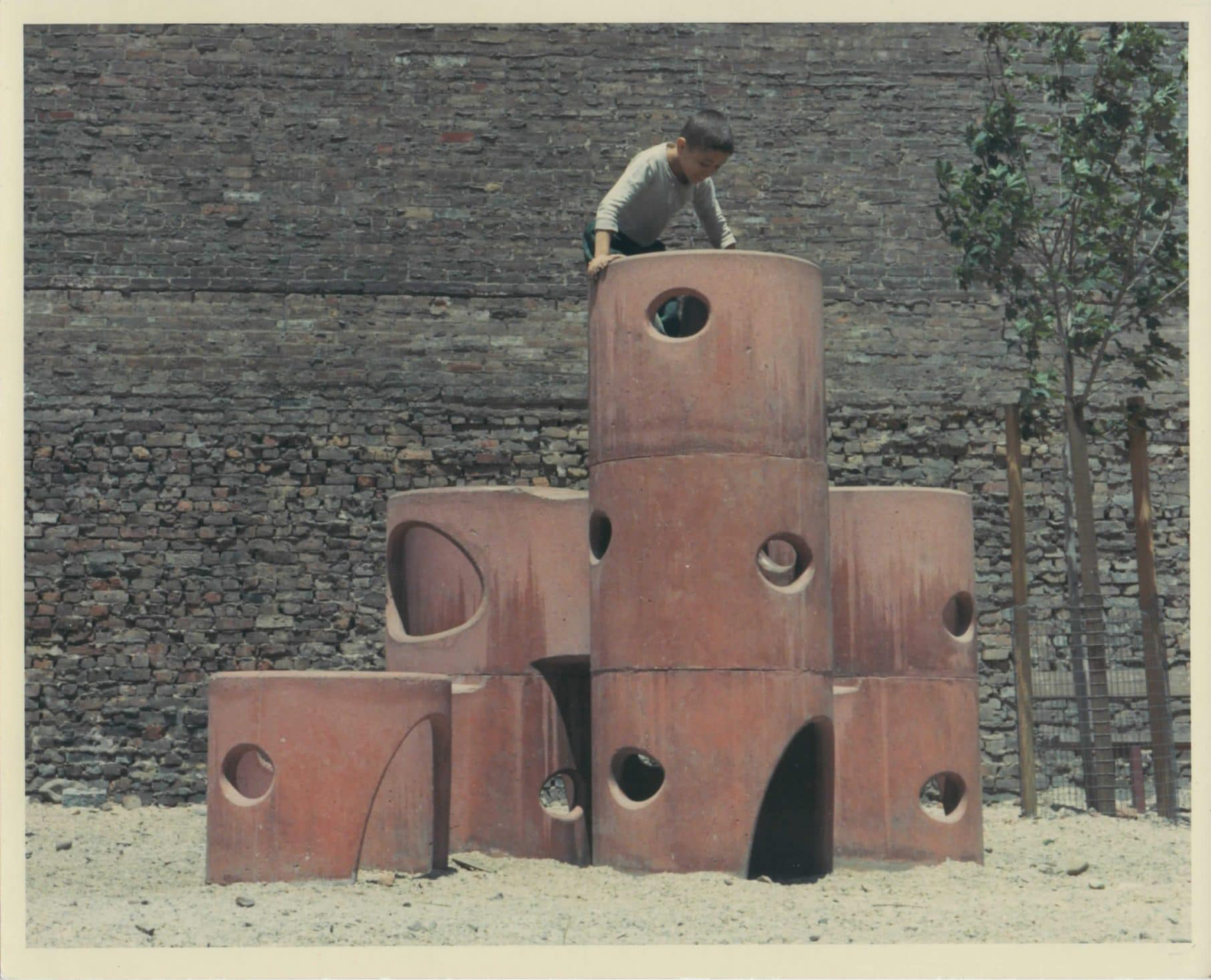

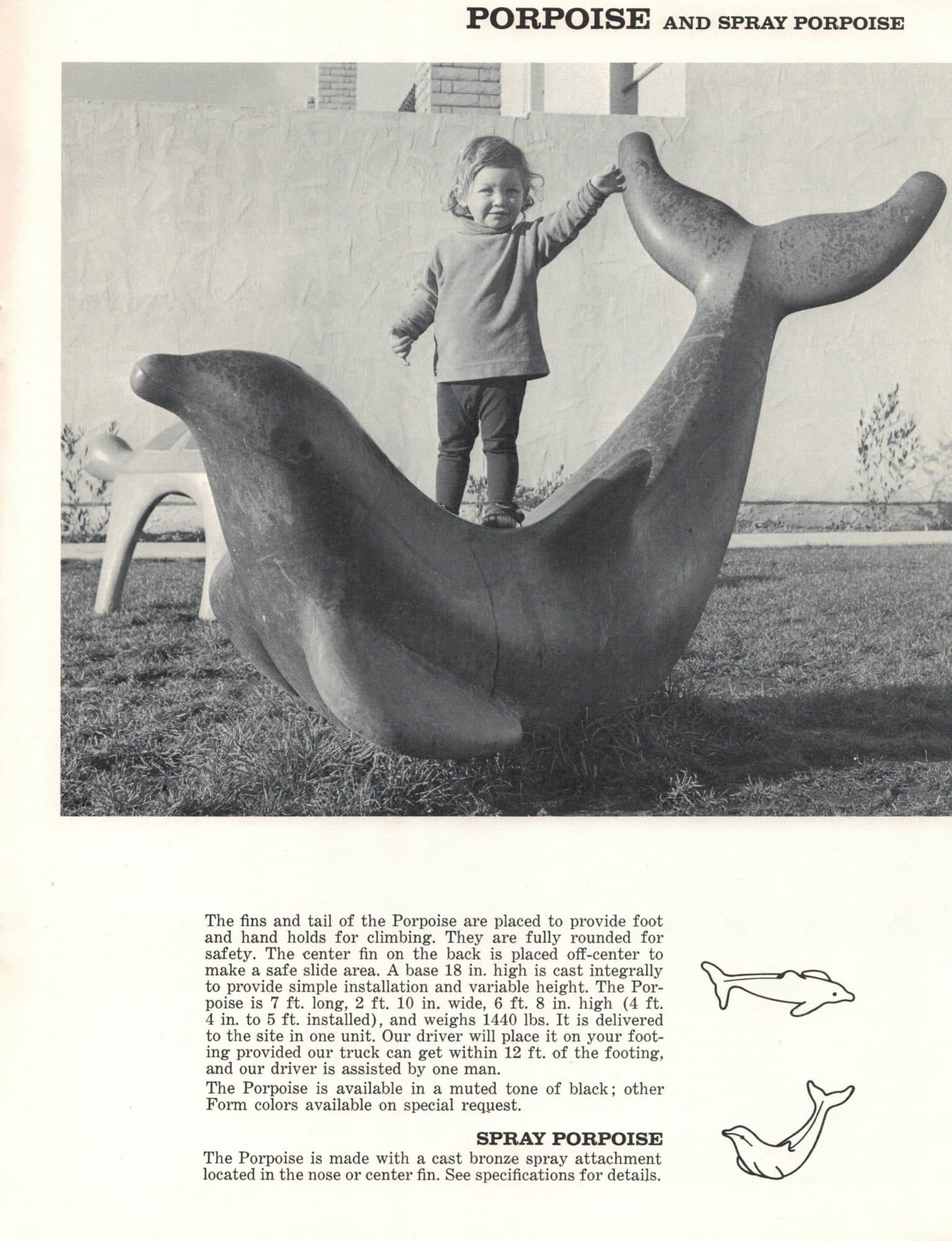

Following in the wake of van Eyck, steel and concrete prevailed as the playscape medium of choice for decades. Artists such as Michigan native Jim Miller-Melberg helped popularize this trend in the United States by fabricating colorful, cast cement play structures on a mass level, allowing customers to easily order by catalog for installation in their schools, parks, and apartment complexes. These vibrant, abstract and animal-shaped sculptures were marketable, small enough to transport, and added beauty and value to public and residential areas.

Further into the suburban expansion of the 1970s and 80s, the demand for playscapes continued to increase. Shopping malls were appearing everywhere, and with them, indoor playgrounds for kids. Pictured here is a breakfast themed play area in a Colorado mall featuring bacon, eggs, and buttered waffles. (Themes such as food and animals can be seen often, especially in smaller-scale designs for younger children.) Not just in malls, the presence of indoor play areas would soon increase as they became a reliable, climate controlled environment where families could take their kids year-round, and capitalists could line their pockets.

Naturally, major fast food restaurants like McDonald’s and Burger King were starting to include complex indoor play areas at their establishments. In 1991 McDonald’s opened a franchise of play places called Leaps and Bounds, which eventually merged with its competitor Discovery Zone a few years later.4 Similar to locations like Major Magics and Chuck E. Cheese, business owners used the child’s need for play as an opportunity for profit. By focusing the design on a specific aesthetic, and adding food and entertainment, these companies were able to monetize on the inherent physical and psychological needs of American youth nationwide. In the 1970s, several spots opened in Michigan called Caesarland, an indoor pizza & play place similar to Chuck E. Cheese, but with Little Caesar as the mascot. In addition to play equipment, many of these businesses also had arcade games, prizes, and food available for purchase. These types of playscapes usually consisted of varied networks of plastic tunnels and slides, ball pits, and nets.

Later into the 1990s-2000s, the presence of playgrounds had shifted significantly as more and more people migrated to the suburbs. Rather than cities and towns having substantial public playgrounds, the responsibility fell more on parents and caregivers to provide play equipment for their own backyards. Often, schools today still have some form of a play area for kids, but products like Little Tikes playsets came along that were affordable and lightweight, allowing children a space to play while at home. The abundance of these brightly-colored interlocking plastic objects is still visible all over, reaching all the way from the inner-city to the smallest rural towns.

Meanwhile, the larger, more permanent outdoor playscapes being fabricated today are very safety-forward, employing materials like bouncy floors, safety railings, and components that are low to the ground. Vibrant hues and synthetic plastics dominate the contemporary style, and there is more accessibility among designs for people with physical disabilities. Over time, the varied designs of playgrounds have adapted to meet the needs of their communities, taking into account geographic location, available technologies, and financial and material resources. In addition, the aesthetic qualities of these structures have consistently been affected by trends in art and design, as well as ergonomics and consumeristic motives. However, it seems that lately the progression of this particular sect of architecture has hit a wall. All the new designs resemble an amalgamation of the old ones—it has been a while since someone came along with a fresh vision that could change the game. Maybe the future path for play is a full circle—as foreshadowed by Hewson’s boulder playscape, in that humans have gone through every rendition that modern materials can make, and now we must turn back to nature—the original playground.

1 Ruper Bickersteth, “Mike Hewson installs giant boulders on wheels for “risk play” space in Melbourne,” dezeen.com, dezeen, January 4, 2023, Link.

2 David Aaron and Bonnie P. Winawer, Child’s Play (New York: Harper & Row, 1965).

3 Anna van Lingen and Denisa Kollarová, Seventeen Playgrounds (Eind hoven: Lecturis, 2016), 20.

4 Nancy Ryan, “Big Mac to Branch out by Leaps & Bounds,”chicagotri bune.com, Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1991, Link. .

Images

Fig.1 Tairalyn Nicole, Untitled, Photograph, Tairalyn.com, August 26, 2015, https://tairalyn.com/diy-little-tikes-home-makeover/.

Fig.2 Mike Hewson, Untitled, Photograph, Dezeen.com, January 4, 2023, Link. .

Fig.3 Author Unknown, A playground on Harriet Island, St. Paul, Minneso ta, Photograph, Museumfacts.co.uk, Accessed March 1, 2023, Link.

Fig.4 Author Unknown, Groot model iglo in het Vondelpark in Amsterdam (december 2019), Photograph, Wikipedia.org, Accessed March 5, 2023, Link. 9.

Fig.5 Author Unknown, A detail of the hexagonal concrete blocks climbing structure, Photograph, Studiodmau.com, Accessed March 5, 2023, Link.

Fig.6 Author Unknown, from Playground and Park, Photographs, jimart work. com, Accessed March 2, 2023, Link.

Fig.7 Author Unknown, Untitled, Photograph, skullsandbacon.com, April 5, 2008, Link. .

Fig.8 The Kleiber Family, Caesarland 2004-35, Photograph, the kleibers.net, May 17, 2004, Link.

Fig.9 Author Unknown, Untitled, Photograph, Photograph, sophustin.top, Accessed March 14, 2023, Link. spx?iid=490328374&pr=39.88.

Fig.10 Author Unknown, Untitled, Photograph, mercari.com, March 3, 2023, Link.