An interview with Ryan Standfest

November 7, 2022

Rotland Press started in 2010 by Ryan Standfest with the publication of FUNNY (not funny). This was a catalog to an exhibition Standfest curated for the now-defunct University of Michigan Stamps Work•Detroit Gallery, which was located on the corner of Martin Luther King and Woodward. The exhibition focused on assembling original art and printed ephemera culled from the world of alternative comics that expressed a sense of dark or black humor. This was followed in 2011 with the publication of the dark humor comics anthology Black Eye 1: Graphic Transmissions to Cause Ocular Hypertension.

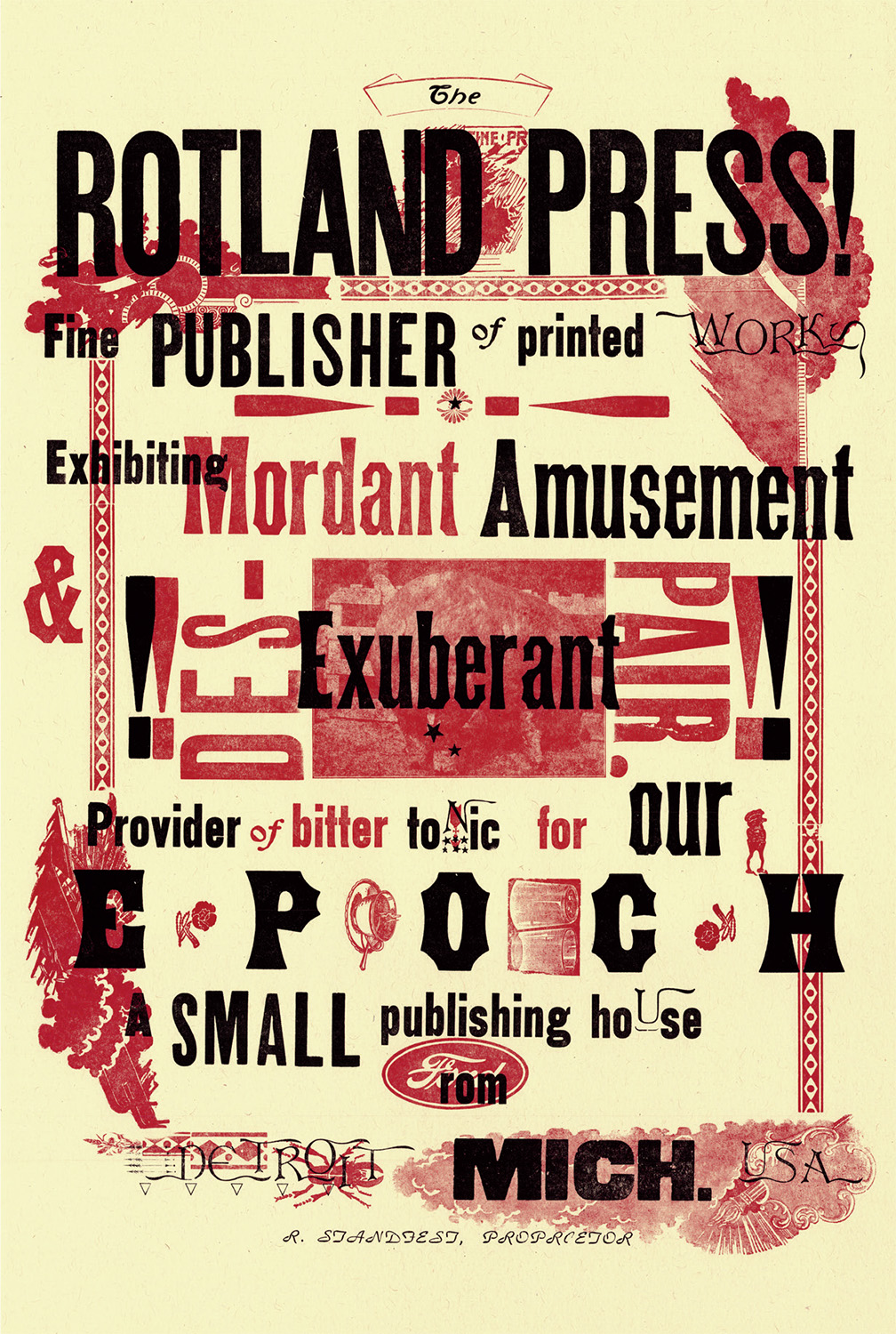

The logo for Rotland Press resembles a round crest or stamp that encourages the viewer to connect the company to very old or even ancient presses throughout history. It incorporates the skeleton of a dog underneath a sun. The logo was designed by U.K. illustrator and designer Ben Jones with the guidance of Standfest, who was inspired when he came across the carcass of a dog on the side of the road one day and considered it an interesting symbol for the press because the way it was arranged suggested a backwards “R” joined with a forward-facing “P” (the tail of the dog curling around to form the loop). Additionally, Standfest says that it is an homage to orange crate art—the labels on crates of oranges that always show a landscape with a rising sun. Only the sun on the logo could either be rising or setting on the dead dog, depending on how you look at it. Since their first published book that included Tom Neely, Stéphane Blanquet, Paul Hornschemeier and other local, national and internationally renown comics, Standfest has continued to work steadily to utilize his knowledge of comics, illustration and storytelling to bring this work to Detroit and send a Detroiters perspective on publishing and curation out into the world. Their work is followed by people all over the place, talked about and collected.

With over 40 books in print, many of them sold out, there seems to be a vast array of different artists included in the collection, however there is a consistency in its visual and literary aesthetic, “mordant amusement and exuberant despair.”

To be specific, the current list of material published by Rotland Press includes:

FUNNY (not funny), 2010

Black Eye 1: Graphic Transmissions to Cause

Ocular Hypertension, 2011

Morose Delectation Exhibition Catalog,

2011, reprinted 2014

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 1 by Ryan Standfest, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 2 by Stephen William Schudlick, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 3 by Andy Gabrysiak, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 4 by Gregory Jacobsen, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 5 by Ian Huebert, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 6 by Cole Closser, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 7 by Onsmith + Sanya Glisic, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 8 by Chris Cilla, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 9 by Josh Bayer, 2013

Rotland Dreadfuls No. 10 by R. Sikoryak, 2014

Chasing Posada! A Macabre Populist in the City, 2014

The Fop by Ben Jones, 2014

Rotland Inquiry: Charlie Hebdo, 2015

Yo Lo Vi (En La Red) by Joshua Johnson, 2015

Rotland Dreadfuls Vol. 2 No. 1

by Marc Brunier-Mestas, 2015

Rotland Dreadfuls Vol. 2 No. 2 by Ben Jones, 2015

Rotland Dreadfuls Vol. 2 No. 3 by John Maggie, 2015

Rotland Dreadfuls Vol. 2 No 5 by Sara Drake, 2016

The Sightseer’s Complement, 2017

American Fly Trap No. 1: The Post-Truth Issue, 2017

American Fly Trap No. 2: The Gun Issue, 2017

The Angriest Dog in the World

by David Lynch, 2020

Funny (Not Funny) Exhibition Catalog, 2010

Black Eye 2, 2013

Mono-Rot: David Becker | Drawings, 2015

Rotland Dreadfuls Vol. 2 No. 4 by Mats!?, 2015

The N-Word: Paintings by Peter Williams, 2016

Black Eye No. 3: A Shameful Enlightenment, 2017

Mono-Rot: Bill Fick | Prints, 2018

Precious Rubbish by Kayla E., 2018

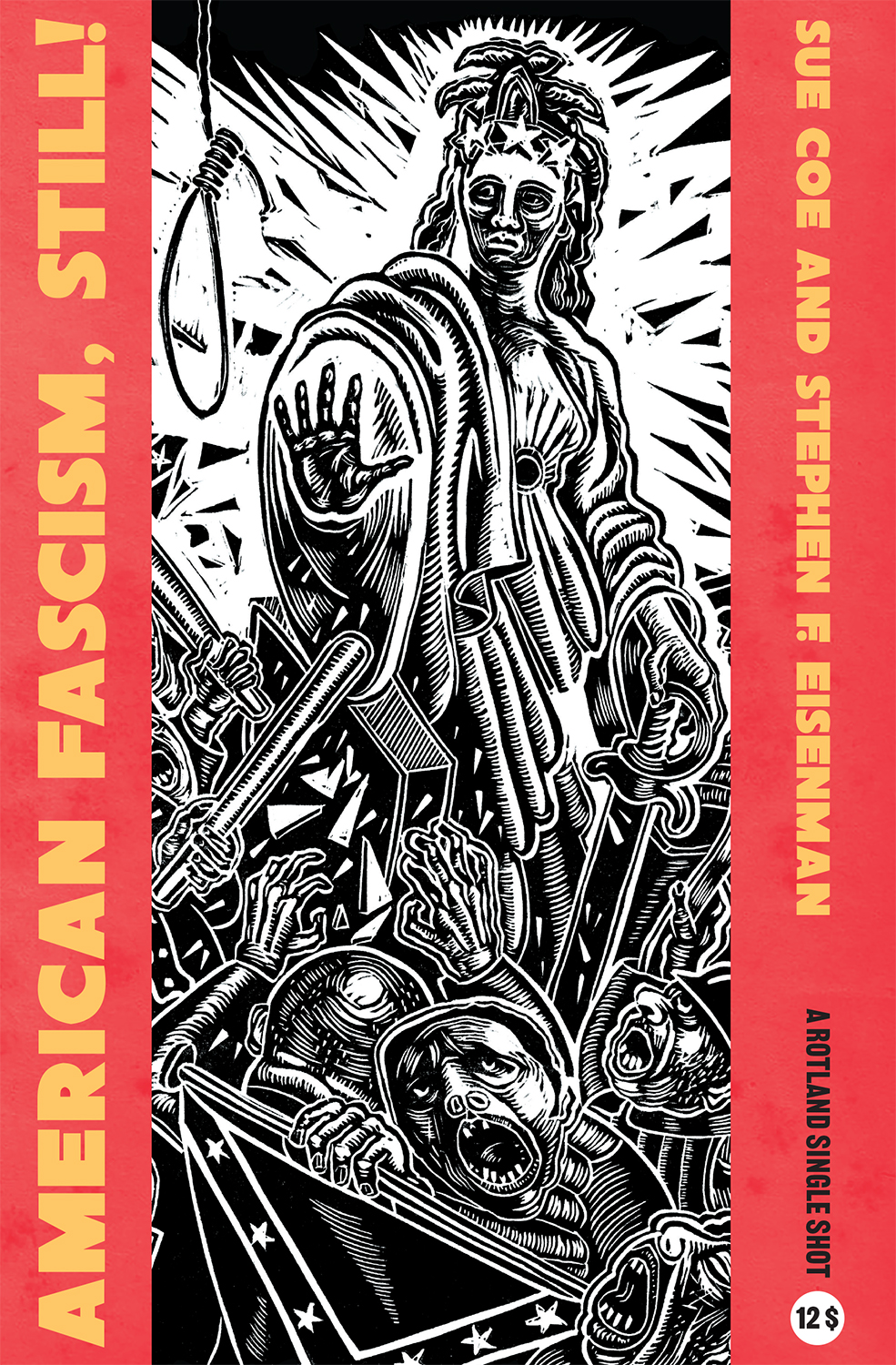

American Fascism Now

by Sue Coe + Stephen F. Eisenman, 2020

The Dreadfuls Special, 2020

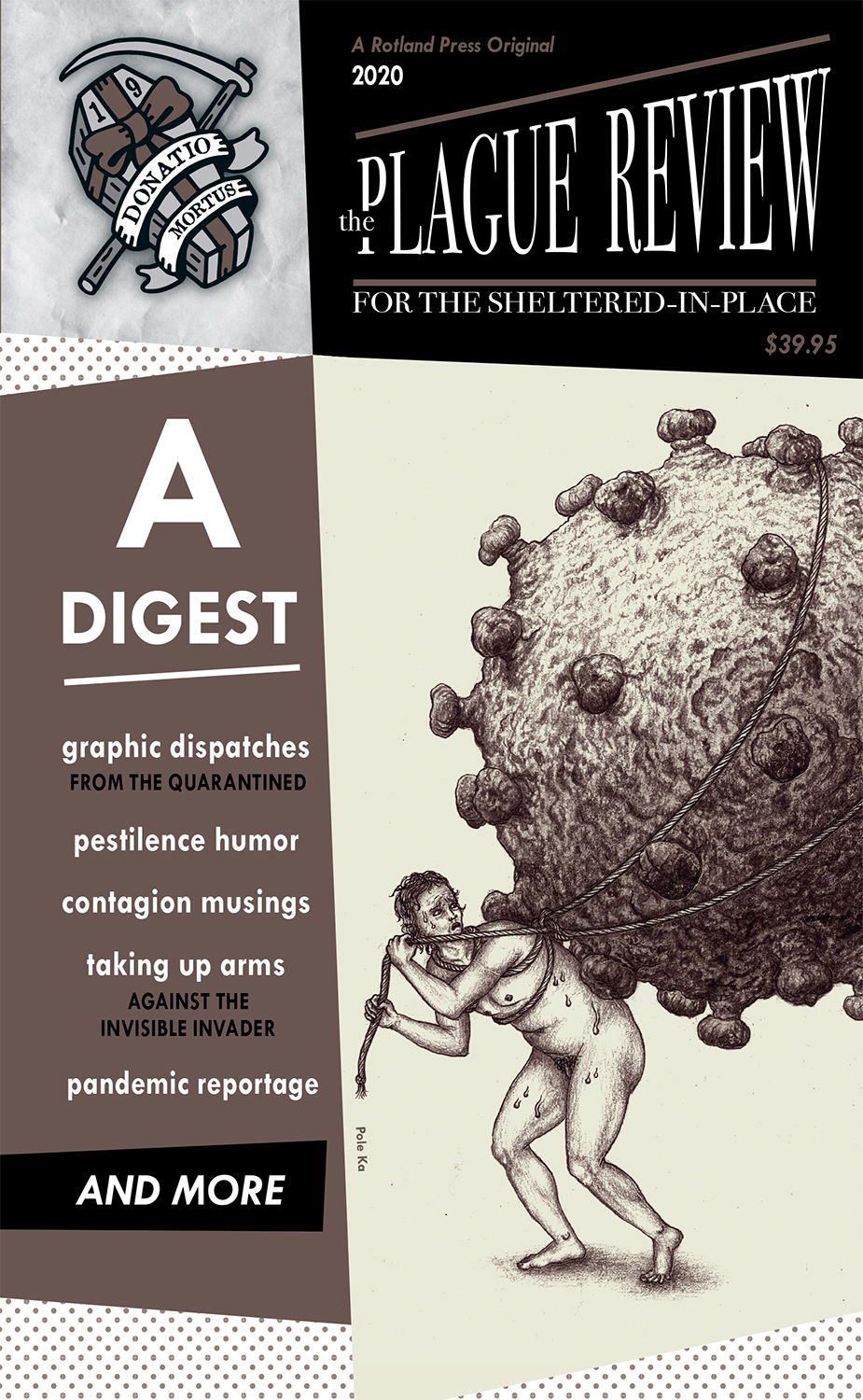

The Plague Review Digest, 2020

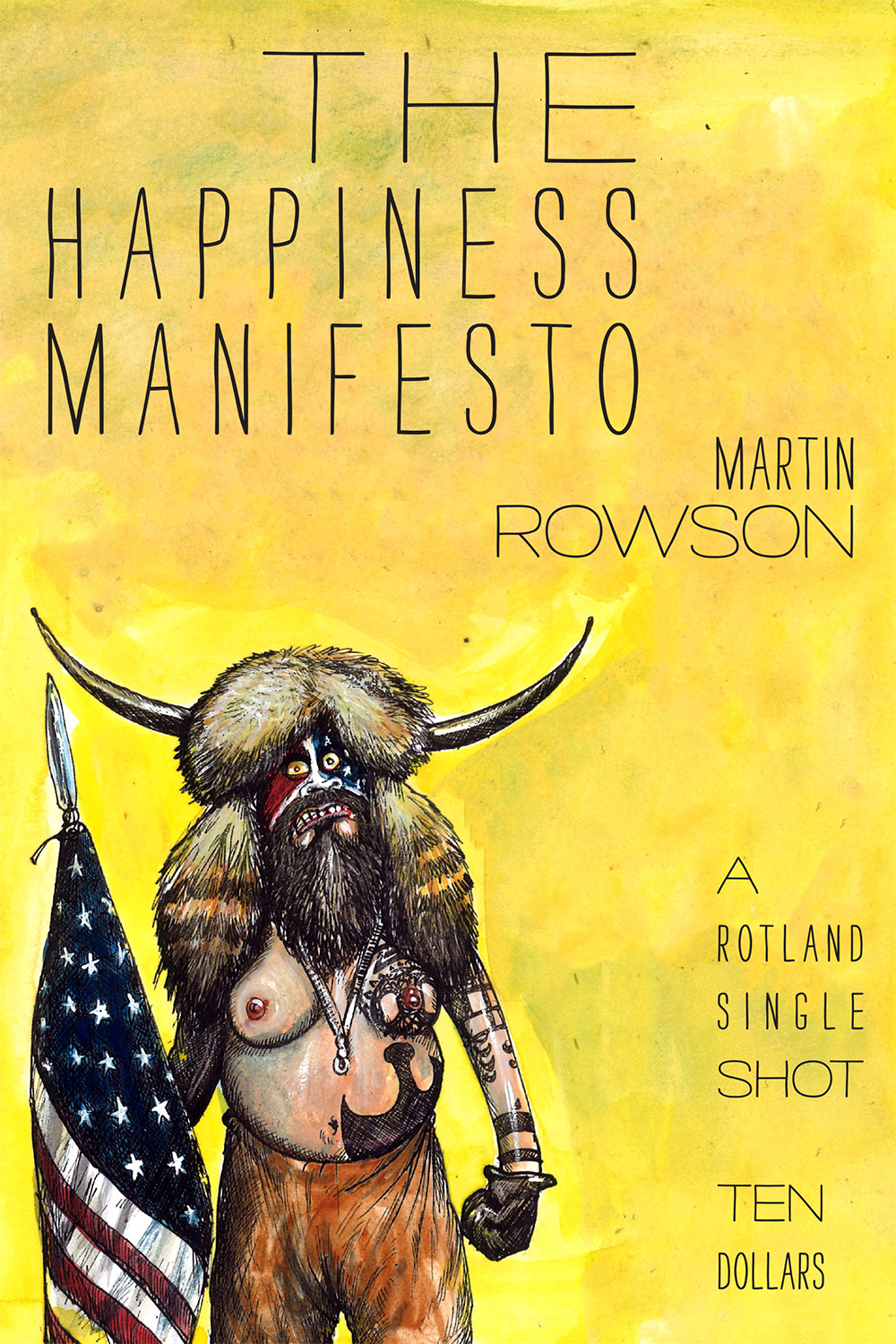

The Happiness Manifesto, 2021

Anatomy of the Devil: Short Stories

by Walerian Borowczyk, 2022

American Fascism, Still!

by Sue Coe and Stephen F. Eisenman, 2022

Active Shooter! by Christopher Sperandio, 2022

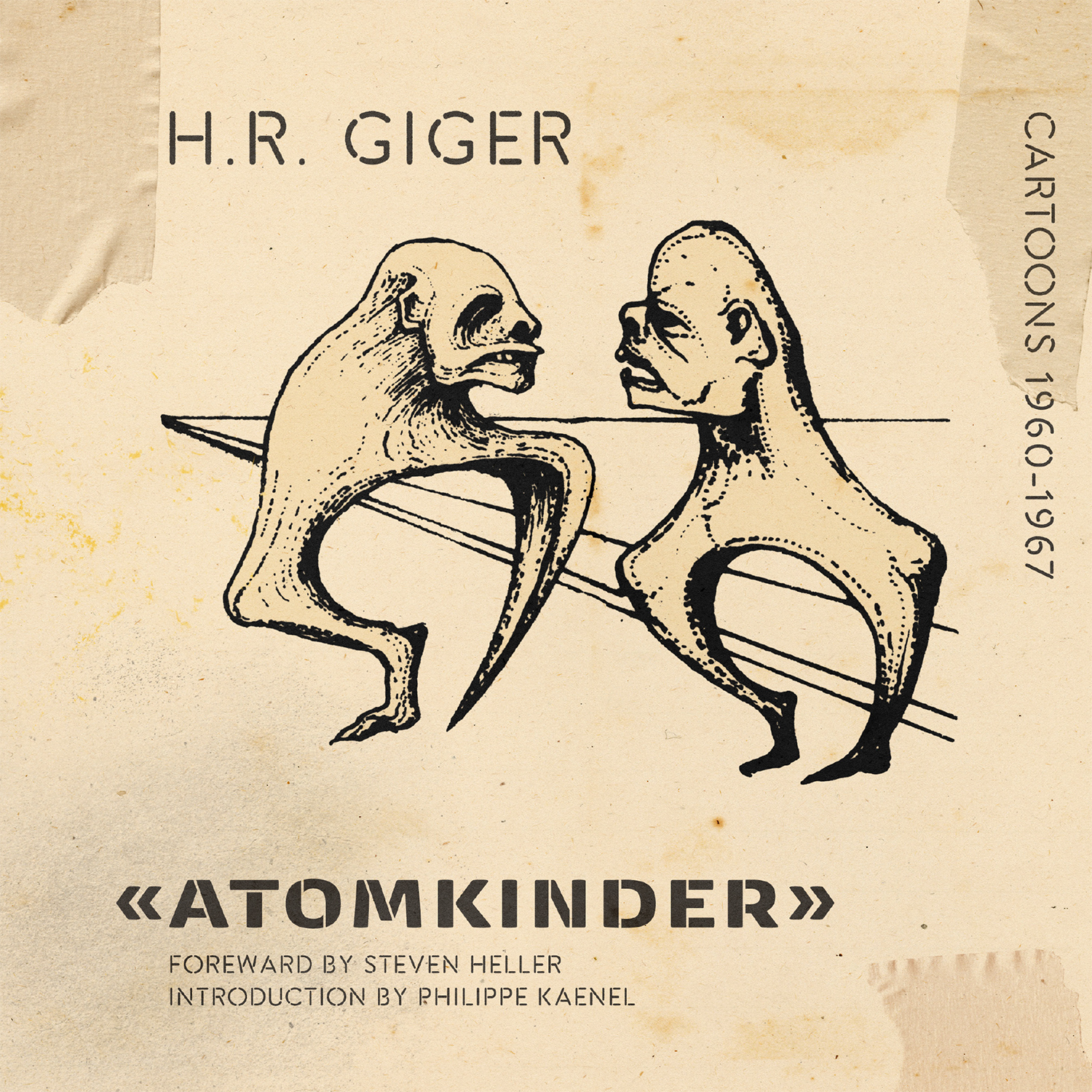

H.R. Giger «Atomkinder» Cartoons 1960-1967, 2022

Runner Magazine: Can you elaborate on the things that you did before you started Rotland Press? How did these activities prepare you to start and manage this publishing business?

Ryan Standfest: Other than being a practicing artist with a philosophy of visual expression I hold dear, nothing prepared me for starting a small publishing house. I wasn’t prepared. In 2007, having just completed my MFA in printmaking at the University of Iowa, I moved to NYC from Iowa City, settling in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. I was restless trying to find employment, eventually stringing together several small jobs per week, based upon what I found in art jobs listing on a given morning. When I wasn’t working, I spent a great deal of time wandering the city, it’s bookstore and music stores and art museums and galleries. I would spend a great deal of time sitting in Washington Square Park with a stack of 3x5 cards that I would make small cartoons on that I called “Rotland Funnies.”

Rotland was a term I used for a screen printed comic strip I made in graduate school. For me, “rotland” was about a state of mind, a land of continual growth and decay, or rot. Anyway, I would make these cards, most of which expressed a rather bleak outlook on life, and eventually I started thinking more about sequences and comics. I had loved superhero comics as a kid, and then transitioned to more adult, dark-humored alternative comics as an adult art school student. At some point, I attended a comics convention at the Park Avenue Armory, and I sat in on a conversation about Humbug, a satirical humor magazine that ran from 1957 to 1958, created by Harvey Kurtzman (who had previously created Mad). Two of the surviving contributing cartoonists to Humbug were discussing their time working on it: Al Jaffee (who went on to contribute to Mad, creating its “fold-in” in the back of each issue) and Arnold Roth (a longtime contributor to The New Yorker, Playboy and the early days of The National Lampoon). These two were in their 80s at the time I saw them, but there was this effervescent youthfulness spilling forth when they spoke of that earlier creative period when the only thing that mattered was putting together a new issue of Humbug. They spoke of not having any money, but taking great joy in the work they were doing, satirizing everything and anything in late 50s America as it was happening. This experience was a lightning bolt that hit me. I had been thinking about the thankless endeavor of making art to hang on gallery walls, beating my head against those same walls, but this was something different: a path forward to find a community and get work out into the larger world. After the talk ended, I went up to Jaffee and Roth, shook their hands and thanked them. I had a spark to publish a book, but I didn’t know yet how.

Flash forward to 2009, when I moved back to Detroit after having grown weary of survival strategies in NYC: I met the illustrator and graphic designer Stephen Schudlich, we hit it off and he offered me a chance to curate a show at the gallery he ran—Work•Detroit. I proposed an exhibition that dealt with comics and dark humor and that I would publish a catalog to coincide under a publishing moniker I called Rotland. The money used to publish the book was the result of me selling at auction a few paintings I owned by an artist who was then in high demand, whom I knew from graduate school. I approached the design of the book, and it’s printing, as I would any printing project of my own. I had no sense that I would keep this going, but now it is almost 13 years later and somehow I have. I’m a little embarrassed by the crudeness of content and lack of editorial vision the books are from these early years, but they proved to be a good foundation and learning experience to define editorial rigor with each new project.

As for the nuts and bolts of running a business, I am STILL working on that with each new project. I guess the press began as a business proper, by accident. I think like an artist, which is to say not a very good business person, so I would make a book without knowing how or to whom I would sell it to. But then, in 2011, when I published my second book, Black Eye (which I funded via Kickstarter), something happened. Copies of the book were being transported by someone else to be sold at the Toronto Comics Festival that year. But when the books went through Canadian Customs, an overzealous border guard took a look at a page in Black Eye, didn’t laugh, and decided the content was obscene. He confiscated the stack and said the books would be sent to Ottawa where a review panel would convene to determine if the book was obscene, and therefore to be banned. Well this incident created a buzz around the book and suddenly I had to figure out how to sell them. I set up a crude WordPress blog with a store and started sending copies out for consignment at various bookstores. The book sold very well (it is now out of print), but was met with disappointment when it was reviewed: since it was potentially “obscene,” people were expecting something crazy, which it turned out was not the case! But still, it sold and I needed to begin thinking about how to continue and to create an actual publishing house with a web shop.

Footnote: the Canadian government got back to me to report that the book was not found to be obscene. The confiscated copies were never returned.

What was your relationship to Detroit initially?

I was born in Detroit (Holy Cross Hospital, East Outer Drive), raised in St. Clair Shores, and did my undergraduate schooling in art at Wayne State University (1999-2002). Then I moved to Iowa City, IA in 2003 to attend graduate school, then I lived in Brooklyn from 2007 to 2009, where I briefly printed (not very well) for Pace Editions and cataloged some animatronic rats at Troma Entertainment (the exploitation movie studio).

But without Detroit, there would be no Rotland. My formative experiences of Detroit—as a child, an adolescent, a teenager and a college student—were of a landscape of shocking contrasts. The foundational narrative of this cradle of industrialized modernity, lifting up the post war dream, and the images that advertised it accompanied by my family’s nostalgia for it, collided with the reality of devastation I experienced. Those images of enormous, gleaming industrial cathedrals rang as an absurdity to me, and still do. The automobile is like a death necklace hanging around the city’s throat. My family was deeply connected with this earlier era—grandfather worked for Parke Davis, grandmother for Packard, another grandfather was a sign-painter and a machinist, an uncle at Stroh’s, my mother worked at Bell Telephone and my father at Fisher Auto Body 21. But those jobs and that version of Detroit, was left in dust. Dust that swirls around in the air still. And it is from this dust that Rotland, an expression of contrasts, emerges. It strikes me that Detroit is not a place that traffics in irony in its image-making. There isn’t a surplus of satirical art unlike Chicago or LA. On the one hand, this surprises me as it is a place of such socio-political calamity and turmoil that a biting rebuke of the systems that caused this decay should be employed. And yet, it is precisely because of the city’s working class roots and ethos, its industry, that the majority of art Detroit has produced is rooted in materiality and identity, and possesses an earnestness that is far from ironic critique. But I think that my journey outward, living elsewhere for a spell and then returning, brought about a distance needed for me to consider trafficking in irony and satire. This is the stuff of primordial reckoning where the identity of the press emerges from. Rotland is a state of mind: a psychological wrestling match with the false promises of yesterday.

I am curious about your ability to collaborate with international people including big names like H.R. Giger and David Lynch and how it came into play…

Well, I do a little research and reach out to people, not knowing if I will get a response or not. I send carefully-written letters and hope that the work I’ve been doing will speak for itself, and that a collaboration is possible. I must say, however, that in my experience, seasoned and established artists who you would think would have no interest in working with me or responding to me, have always done so, even if it is to say “I’m a bit busy now, but please reach out again in a month or so.” Whereas younger, less-established “kids,” fresh out of art school, with no track record, are terrible at responding. I have found that older artists have been very understanding, fair and generous with their time, whereas the younger crowd simply says “what’s in it for me?” mistaking what I am doing for the building of a lucrative empire. That, of course, goes nowhere fast. I find myself working less and less with younger artists these days and instead seeking out “dream projects” with people I have always wanted to work with or trying to tackle books I’ve always wanted to see exist.I feel secure enough that I can do this now. Remarkably, when I reached out to the twin animators/filmmakers The Quay Brothers (Timothy and Stephen Quay), to design the cover for the book Anatomy of the Devil: Short Stories by Walerian Borowczyk, their response was so enthusiastic, their conversation so engaging, that it mystifies me that when I contact a Detroit-area artist with barely a blip on the cultural radar, I am met instantly with a combination of skepticism and dismissal.

I feel that in 2020, during the lockdown, something shifted in my desire for the press. In the previous year, I was seriously thinking of ending what I considered an expensive and failed “experiment” in publishing. But during the lockdown, I had a renewed interest in assembling and getting books out to the world. After publishing the last anthologies Rotland will ever make, The Plague Review and The Dreadfuls, I also felt a need to steer away from a focus on comics and a move toward art, literature and other things in-between. To redefine the products of the press, but to maintain the sharp, expressive edge that it has (in other words, its worldview).

As I mentioned above, there is a particular visual and literary aesthetic that underlines most of the work you publish and that is nihilistic despair. What is it about this perspective that you feel is interesting and relevant to our current times?

I wouldn’t characterize Rotland Press as being taken up with “nihilistic despair.” There is a lot of humor there. Humor, by its very nature, suggests a release, rather than the pure suffocation of despair. Nihilism suggests an absence of beliefs or ideological aims. Some of the earlier publications I assembled could run the risk of nihilism, and I am unhappy with much of that work, but I consider myself to be a disappointed idealist who believes that things should be much better than they are. Rather than suggesting that everything should be burned down, I prefer to think that some of the products of the press take aim at those “active agents of ignorance” that prevent our species from evolving. I find that the older I get and the more I feel the world is going through a painful period of realignment, the more I wish to publish work of a political nature that confronts our era head-on. The floodgates have been opened up to release all the venom coursing through our nation’s veins, with racism, sexism, homophobia, and just plain appetites for destruction overflowing from the gutters. The three most recent Rotland publications from this year, are all political in nature, and are all about using a cheaper print medium, with “lines on paper” to push back against ignorance. “American Fascism, Still!” by Sue Coe and Stephen F. Eisenman, confronts our slide into authoritarianism, with a combination of stark, graphic imagery reminiscent of the anti-fascist work of Weimar-era artists who warned the world of Nazi encroachment. “Active Shooter!” by Christopher Sperandio, uses the medium of cowboy adventure comics from the past to satirize the madness of our gun culture and its blind obsession with portable death machines. And “H.R. Giger «Atomkinder»” is a look into the relatively unknown early cartoons of a young H.R. Giger, who came to the attention of the world in Swiss and German underground publications of the 1960s, with cold-war satirical work that took a stance against the madness of nuclear armament.

I don’t seek out relevance as if I were scanning the news for a current hot button topic, but I am interested in work and artists who have demonstrated a long-term commitment to issues that have always been present and indeed are still a part of our cultural discourse. I have to be in love with the work first. It serves no one if I am using the press as an advanced form of virtue-signaling. There is a longer, more committed endgame that matters.

You can keep up with the work of Rotland Press on their website here:

http://rotlandpress.com/