Kellen MacGregor

January 17, 2022

In the summertime of 2018, I met Madeline Kuzak for the first time through one of my closest friends: her younger sister Lydia. Movement Electronic Music Festival had just begun, and I was staying with Lydia, the first friend I made in Detroit, while she showed me around the city, introduced me to her friends and two older siblings, and took me to various Movement after-parties. I was apartment-hunting at the time, more than ready to move to Detroit from my hometown, a fly-over unincorporated community about an hour and a half northeast of Detroit. Lots of cornfields, tractors, and cars passing by toward farther destinations decorated the small town I had spent twenty years in.

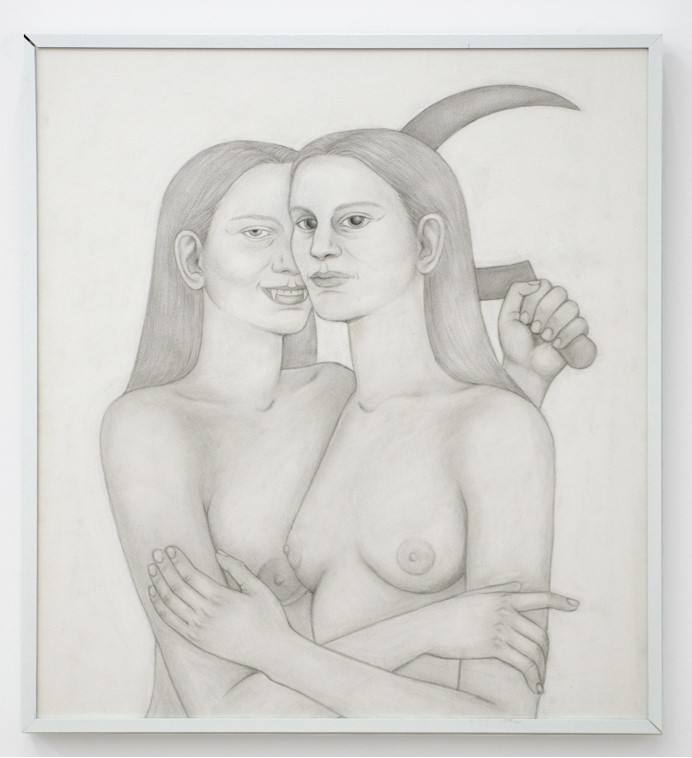

Within a couple of days spent acquainting myself with Detroit, I had met Lydia, her older brother Gen, and Maddie. I instantly awakened myself to the siblings’ collective yet uniquely distinct artfulness: Lydia’s drawings and paintings connect ostensibly dissimilar eras together to enmesh one period’s fey drama with another period’s mysterious traditions and rituals; Gen’s erotic videography and photography combat cis-heteronormativity throughout the arts, exploring butch masculinity, pornography, and gay and lesbian themes and aesthetics; and Maddie’s oft-macabre artwork tells tales of besmirched, vengeful, and chthonian figures standing, crawling, or plotting within minimal yet emotive sceneries.

Maddie Kuzak’s work has been shown across the United States, from Los Angeles to New York City, granting a glimpse into internet-laden aesthetics alongside horror tropes, melding into a singular, one-of-a-kind practice that transcends the current zeitgeist of Millennial and Gen Z art, piercing through the online and the in-person. Maddie agreed to commence an email correspondence with me, and what transpired soon transformed into an exploration of her upbringing, influences, hot takes, and shrewd cultural and art criticism.

Kellen: Thank you for agreeing to partake in this interview. Your artwork has awed, intrigued, puzzled, and challenged me! Thus, it’s an honor for me to be able to interview you for Runner Magazine; I’m excited to see what this will transform into! I must admit I’ve spent a lot of time and energy ruminating on how to best conduct this correspondence, though I enjoy the idea of email and how it reminds me of penpalship, back when people used to write letters to one another constantly. Hauntingly, this form of correspondence harkens back to a time about which most feel nostalgic, leading to my first question: How does nostalgia, or this idea of the past haunting the present/future, work into your art practice, if it does at all?

Madeline: The idea of the past haunting the present/future is definitely an important part of my work. In Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, his essay where he introduces the concept of the death drive, he posits that all life on earth has an instinctual yearning to return to an inorganic state (non-existence). Nostalgia could be connected to the death drive because our nostalgic memories are colored with the illusion that the past was somehow simpler and we ache to return to that moment, and the urge to return to a simpler moment is ultimately the urge to return to non-existence. The past haunting the present and future is a burden we all share that we can either ignore (and be completely controlled by our past) or explore and understand in order to move beyond a self-imposed purgatory of repeated behaviors and scenarios. In my drawings and paintings, there is always a loose narrative at play, and I get a sadistic satisfaction in imagining that the subjects in the narrative are trapped in a moment forever, like purgatory. In my sculptures, I like to imagine them as haunted with some mysterious significance that will never be fully understood. The concepts of hauntings and curses, which are metaphors for the past weighing on our lives, will always be relevant to my work.

K: The metaphoric morals found in fairy tales and folktales remind me of Freud’s concept of the death drive, wherein folklore entraps its characters in these almost Sisyphean tales, cyclically repeating quests or misadventures to convey tales’ morals to their listeners — all purgatorial. Are the subjects of your paintings and drawings inspired by folklore? If so, is there a storytelling element in your practice?

M: I am definitely influenced by folklore, but I think I am more influenced by film, which is obviously a storytelling medium. A film like The Shining has all the same elements as a folktale and is so iconic and easily projected upon by the audience because of the simplicity of the story: a father, mother and son in a haunted hotel. I want to capture the same simplicity of the folktale mixed with an awareness of the world around me without ever consciously injecting the work with a meaning or a morality. I guess Stanley Kubrick is my ultimate influence because he was such a master of enrapturing the viewer, but at the same time maintaining a kind of detachment which gave the audience the space to connect with a film in their own way. The ultimate humanitarian move as an artist is trusting that art has its own function in the world instead of believing it’s a vehicle for a message. Art is beyond language and morality!

K: Have you ever found yourself in a haunted building, whether it be a house or hotel?

M: I don’t really have any good ghost stories. I’m so jealous of people who have had those experiences. I spent part of my childhood in Japan, and we lived in a traditional old house that looked exactly like the homes in all the Japanese horror movies that were getting American remakes in the mid-2000’s. Tatami mats, sliding doors, a steep dark wood staircase. I was really scared of the dark in that house, but I never really had any supernatural experiences.

K: I have never seen a ghost either, though I am also envious of those who have! Would you say the house you grew up in and the films you’ve watched in Japan inspired your artwork? I do see a connection between some of your pieces, such as Truth Emerging from Her Well to Shame Mankind 2 and late-90’s and early-aughts Japanese horror films such as Ringu or Audition, which, like Truth Emerging, allow for the emergence of a vengeful, monstrous anti-heroine. Likewise, the figures in your piece Reprimanded from 2019 seem to belong to a timeless horror film wherein a voyeur watches a woman clad in business attire pull the hair of a pregnant vampire; as a follow-up to the previous question, what role does darkness, in any sense of the word, play in your work?

M: I’m really drawn to the trope of the vengeful female monster. In some sense, I use it as an avatar in my art. In Truth Emerging from Her Well to Shame Mankind 2, I was inspired by the painting of the same name of a screaming woman emerging from a well with a whip in her hand. The painting also inspired the iconic image of the girl emerging from the well in Ringu. The painting depicts truth as an unstoppable force personified by a monstrous woman. It’s a hopeful thought, that truth is an unstoppable force. In Ringu, an unstoppable curse is also personified by a female monster. You could analyze the image of the well in the painting and the film as a representation of the subconscious and the women emerging as repressed feelings, desires, or impulses. Darkness in general can represent the subconscious. In some ways, my art is an outlet for my subconscious and the entire process is like a digestive system where the subconscious is the stomach, and the art is the waste (repressed content ejected from my body).

K: With that cycle in mind — art as an off shoot of digestion — do you believe most artists suff er from irritable bowel syndrome? If so, what role does IBS serve in the metaphorical digestive process of artmaking?

M: That’s a really interesting question! I don’t know if all artists suffer from IBS, but I definitely think all artists could be placed on a coordinate plane with quadrants for a personality disorder, ADHD, autism and IBS. I just think making art in particular is scatological. Art relies on intuition, which seems to live in the stomach (“gut instinct”). It all goes back to the stomach. Looking at bad art is like looking at something someone forgot to flush. I guess I’m focused on the stomach because art-making and art-viewing is a visceral experience that is centered in the stomach for me and sometimes in between my legs.

K: Are there any art movements that you believe, whether past or contemporary, are clogging the pipes?

M: I hate murals. I’m not talking about murals as a medium like Diego Rivera’s, I’m talking about the hideous, algorithmically generated street art on every building in every city. Murals are disguised as sentimental tributes to a city or neighborhood, but they’re all painted by some guy from Los Angeles and they’re just advertisements for speculative real estate because they represent an “up-and-coming” area. The aesthetic of these contemporary murals is an appropriation of street art, an art-form that was once subversive because the artists were originally dis-empowered people making a mark on their environment. But these days when you see a giant painting of, like, a blue woman crying a rainbow tear, it’s the rich marking their territory. It’s the neoliberal version of a totalitarian regime hanging their flags everywhere. And the sad thing is, there is still lots of “authentic” street art, but it’s side-by-side with the simulacra. Neoliberalism takes every aesthetic of rebellion and alienates it from its origin. “Authenticity” itself is a commodity these days. There’s no escape, but one thing we need to do as artists is to be hyper-aware of the images and information that are shoved in our faces all day. Best-case scenario, you spend a couple hours reading and doing research for your practice most days, but the rest of your day is filled with images and information that affect you just as much. Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord is more relevant than ever and is free to read online.

K: Like murals, what else in the art world reeks of neoliberalism?

M: Everything, unfortunately! The art world, like real estate, is a place for the rich to hide their money. Neoliberalism is inescapable; it’s woven into our identities. Millennials and Gen Z were all raised to think that we might be a “chosen one” as opposed to a member of society. Like a singular genius who is above society. For example, the contemporary cliché of parents looking at their child and thinking, “They could be the next president or find a cure for cancer!” I think so many people want to be artists because it’s harder to measure artistic genius. It’s such a sick neoliberal Randian idea that our existence is only justified if we’re geniuses. Imagine if we didn’t have any plumbers or electricians or sanitation workers, but we were all “entrepreneurial geniuses.” Society would collapse and we’d all be naked, jacking off to our reflections in dirty mirrors and dying of tetanus.

K: Do you have any guilty neoliberal pleasures, artist-wise? I think Jeff Koons is funny — if you’d consider him neoliberal — especially his balloon animal fetish.

M: I actually like a lot of Jeff Koons’ work. I love his series of photos with Cicciolina; if I was rich, I’d have those photos hung on my walls. I don’t have any guilty pleasures in regard to art because so many of my influences would not be considered fine art. Anyways, the taste of the fine art world is so rotted that taste isn’t coming from the top down anymore. The upper class aren’t even into fine art, the average rich guy’s idea of art is basically a T-shirt graphic from Spencer’s or something so derivative that it seems like a put-on. So, I think the idea of good taste and bad taste and guilty pleasures is kinda dead. People only make those judgments in the context of their little subcultures which don’t usually influence people outside of them.

K: Do you see subcultures surviving neoliberalism’s homologous, stifling tendencies?

M: I think subcultures have proliferated because of the internet. Mainstream media seems completely independent of the “zeitgeist.” In fact, it functions to keep us from uniting over our shared struggles, so instead everyone suffers quietly and yearns for something or someone to mirror their thoughts and feelings. I think everyone is seeking a subculture. A huge indication that mainstream culture is fundamentally dysfunctional is the phenomenon of people middle-aged or older seeking out internet subcultures such as QAnon. Subcultures are historically associated with young people because normally they’re the broadest demographic to feel neglected by mainstream culture, but now everyone feels that way!

K: How would you describe the zeitgeist of the 2020’s so far?

M: I think it’s too early to say, but I have been thinking about two main trends for artists under 40 in the last few years. One is a fairytale aesthetic and the other is a dystopian refuse aesthetic. In my opinion, the fairytale aesthetic is based on an awareness that we live in a dark age of ideas, and fairytales are a timeless and universal form of communication. It is pretty broad as a trend, and there are many subcategories. The dystopian refuse aesthetic is a bit more straightforward. It’s usually expressed in sculpture and seems visually inspired by the films of Ridley Scott and David Cronenberg. The sculptures usually seem like garbage from the future or some fragment of alien technology, sometimes with a body horror quality. I think this is a trend because we really don’t have a vision for the future besides chaos. The Mark Fisher quote, “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” is particularly relevant to this aesthetic.

K: What do you have planned for the future?

M: Well, in about a week I’m going to Miami Art Basel. I have a couple of group shows coming up. I want to start a podcast or get back into playing music and performing. I plan to eat healthy and exercise daily.