Ashley Cook

March 28, 2025

Warp and Weft: Technologies within Textiles at The Shepherd. Image Courtesy of Library Street Collective

Although their first public event took place in 2019, The Shepherd is considered one of Detroit’s newest cultural arts centers. Its official grand opening in May of 2024 was celebrated with their inaugural exhibition Charles McGee: The Time is Now. The event coincided with a larger event featuring the various properties of Library Street Collective’s Little Village, a community of arts-based organizations on the East Side. As a central feature of Little Village, The Shepherd, built in 1911, is a monumental piece of architecture designed by the Detroit-based firm Donaldson & Meier, who also laid blueprints for other significant structures in the city including the David Scott Building, the Penobscot, and the Belle Isle Casino.1 Many of their early sanctuary commissions followed the traditional Romanesque style, which was popular in the early 20th century when they were hired by the Church of the Annunciation to develop 1265 Parkview Street. The building was acquired by LSC in 2019 after three years of inactivity, who announced their plans to repurpose the 110 year old place of worship into two gallery spaces, a library for Black arts, a bed and breakfast, a skate park and a sculpture park. Warp and Weft: Technologies within Textiles is The Shepherd’s fourth exhibition.

Blink, James Benjamin Franklin, 2024 Acrylic, fabric, plaster, mica, and epoxy on extruded polystyrene. Image by Ashley Cook

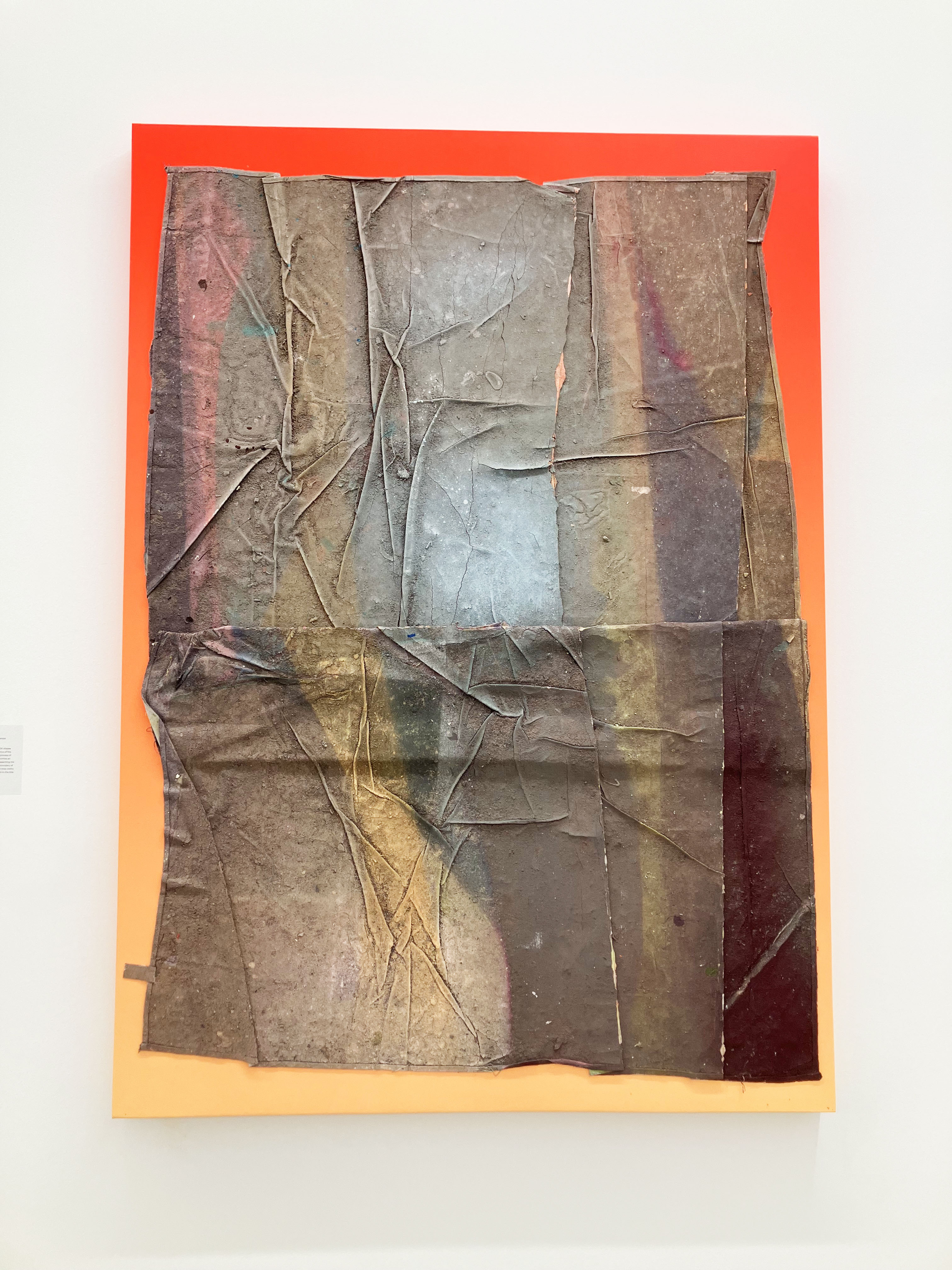

Self_portrait_2022-2024_1a, Jason REVOK, 2025, Synthetic polymer and mounted drop cloth on canvas. Image by Ashley Cook

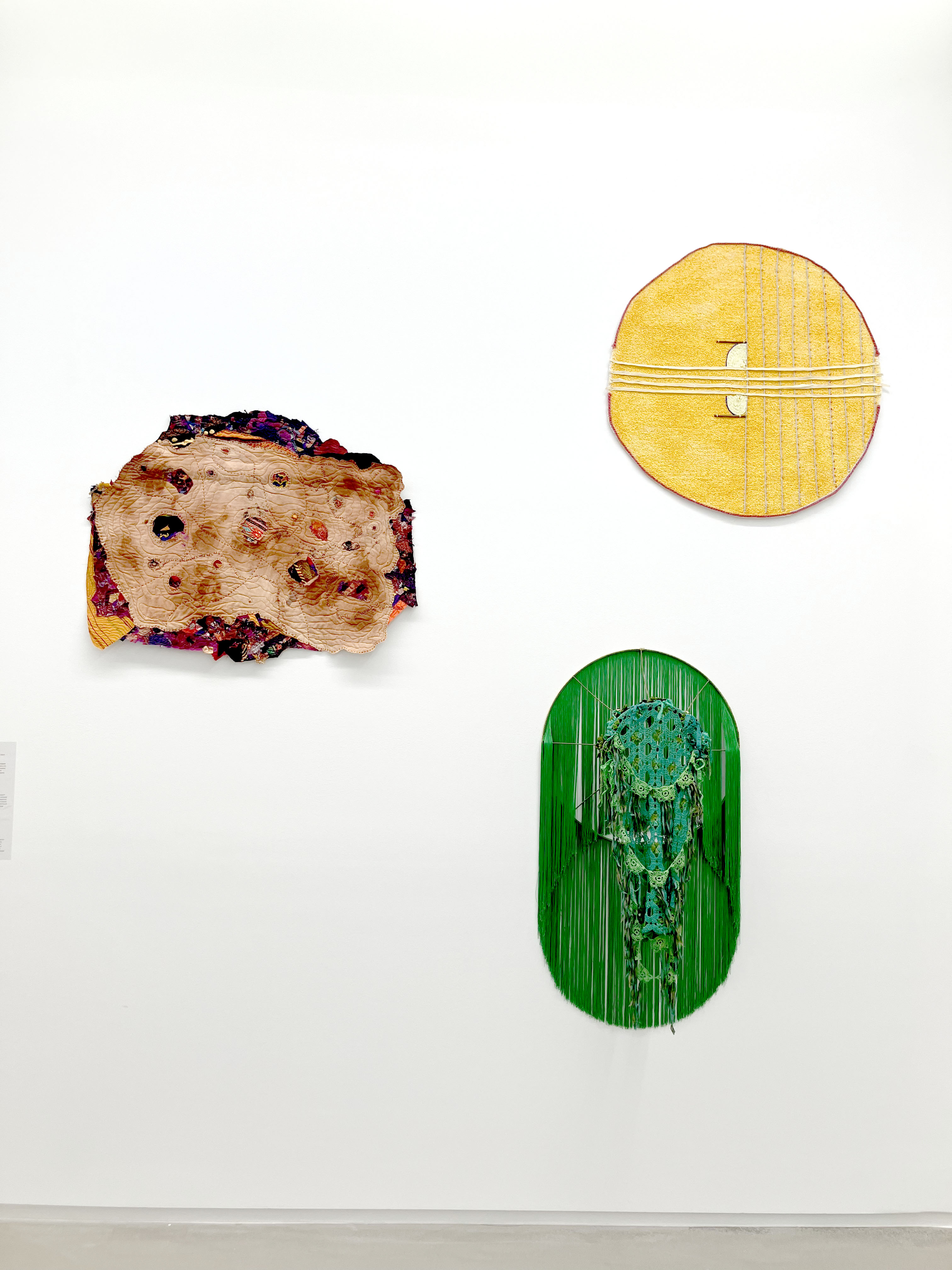

(Left) Traces Remain, Carole Harris, 2024 Miscellaneous fabrics, rust dyed, acrylic paint, machine and hand quilted, hand embroidered

(Top Right) Soft Light, Teresa Baker, 2024 Beads, buckskin, acrylic, artificial sinew, yarn on AstroTurf

(Bottom Right) Askance, Melissa Webb, 2022 Hand-dyed and crocheted yarn and vintage cotton textiles. Image by Ashley Cook

This broad survey of textiles in contemporary art comprises thirty-six artists of various backgrounds, methodologies and concerns. The press release — written by The Shepherd’s artistic director and the curator of the show, Allison Glenn, guides visitors from one piece to the next by highlighting the wide scope of conceptual foundations at play. The themes range from the relationship between humans and technology to new interpretations of traditional techniques, the passing of time, the physical manipulation of fabric, familial connections, adornment, pedagogy, industrial weaving, and fashion. With each work functioning as an entryway into its own universe of discourse, reading Glenn’s overview of the show feels a bit like speed dating. While the “all-inclusive” nature of the exhibition provides the viewer with a playground of beautiful surfaces to explore, a more pointed approach to the subject indicated in the title could benefit a creative community that is hungry for critical conversations. The previous show, Grace Under Fire, curated by Laura Dvorkin, Maynard Monrow and Kyle DeWoody, was similar in that it assembled the work of forty-five different artists to explore “how we continue to find hope in difficult times”.2 Both shows bring world-renowned artists into the Detroit creative ecosystem—an essential move to expose the local community to art outside of the city—but these super packed group shows tend to hinder the message, turning them into overwhelming spectacles instead of judicious inquiries into chosen topics.

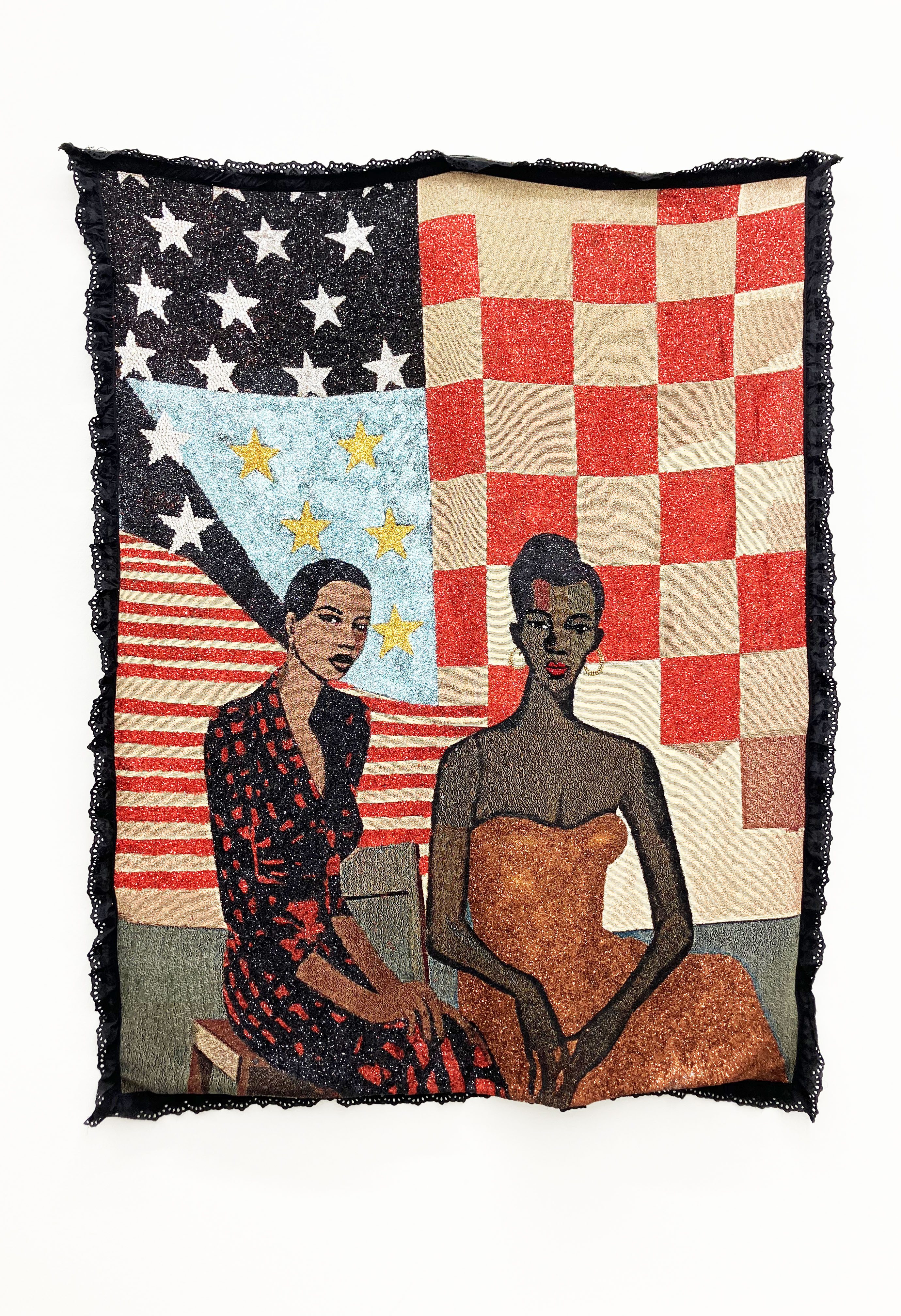

American Girls, Akea Brionne, 2025, Jacquard, glitter, rhinestones, cotton, thread. Image by Ashley Cook

De India y De Negra; Lobo, Joey Quinones, 2025, Cotton, lace, trim, beads, cochineal, paint, stain, wood. Image by Ashley Cook

we are ALL safe, Alisha B. Wormsley, 2024, Cotton and wool. Image by Ashley Cook

Big Toe, Gary Tyler, 2024, Burlap, yarn, metal snaps, fabric and batting panther has googly eyes. Image by Ashley Cook

SHE in Gold Form, Nep Sidhu with Nicholas Galanin and Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, 2024, Poly-Cotton, elastics, wool and various materials. Image by Ashley Cook

Centering a craft as ancient as textiles, and linking it to technology, does, in itself, spawn curiosity. Dating back to prehistoric times, the spinning and weaving of organic fibers has become deeply embedded in the history of humankind, contributing to our survival and development of cultural identity. In an era where humans, cyborgs, and robots coexist, the fear of losing our humanness to technology has become a common concern.3 But the pixilation used to render artificial intelligence actually finds its origins in the loom; its ancestor is the hand-woven tapestry. The Industrial Revolution brought with it many systems that required collaboration between human and machine, one being the Jacquard Loom. This human-operated instrument automated textile production through the use of binary code—a mechanical technique that evolved into the digital information structure that is used today by computers to store and process data.4

It is human instinct to weave. For over 100,000 years, elements of the world around us have been incorporated into our furniture, clothing, hair, and stories, contributing to increasingly complex physical and conceptual networks that wrap the globe and transcend materiality. The relationship to the post-internet world fluctuates amongst the selection of artists in the Shepherd’s current exhibition. Superimposition of visual elements is one indicator of influence coming from the world wide web. Rainbow Mountains First Moon by Liz Collins, De India y De Negra; Lobo by Joey Quinones are two examples that teeter the line between URL and IRL through their simultaneous use of digital and manual techniques. A similar type of visual contrast can be found in the age-old practice of quiltmaking, which explored rhythm by combining various distinct colors and patterns into one composition. Cyrah Dardas harkens this tradition through Return to Rain and Jupiter Blue Moon. Works like Whole Cloth by Marin Hassinger or Traces Remain by Carole Harris iterate a sensation of weightlessness that resembles the malleability of form and space only possible in digital realms. As we contemplate the show’s use of the term “technology” in relation to all of the work, it may be worth detaching from a focus on electronics specifically, and honoring its definition as “the practical application of knowledge, especially in a particular area”.5 This alternative perspective could allow for a more straightforward and holistic interpretation of the exhibition, framing the show as a means to express appreciation for textiles as a staple of human existence, and a way to acknowledge its infinitely expansive potential as a creative medium.

As the forty-five works on view flow from the two galleries out into the space of preserved adornment, the perception of the work becomes increasingly influenced by remnants of the preceding parish. Similarly, There are a number of contemporary art spaces that were originally built by religious organizations: Kunsthalle Osnabrück in Germany was formerly a Dominican monastery, Sant’Andrea de Scaphis in Italy was the Church of Sant’Andrea de Scaphis, Singapore Art Museum was a Catholic Boys School. To repurpose these epic structures is ambitious no matter what they are destined to become. The weight of theological association can be challenging to neutralize enough for the art to sustain a voice that is independent of the architecture. The decisions of the architects at Peterson Rich Office allowed for The Shepherd to share essential features of a proper “white cube” art space while also preserving historical elements. The Shepherd’s program has thus far effectively mingled local, national and international artists, all of whom have carved their place in the world of contemporary art over many years. Having an exhibition space with the resources to bring such work into Detroit is refreshing and very much needed to inspire and inform artists practicing here. However, curbing the tendency to throw massive group shows in exchange for more carefully curated experiences could help boost its role as a key venue for contemporary art both locally and abroad.

Warp and Weft: Technologies within Textiles at The Shepherd. Image by Ashley Cook

Warp and Weft: Technologies within Textiles opened January 25, 2025 and will be on view until May 3, 2025.

Featured artists: Lisa Alberts, Teresa Baker, Kalyn Fay Barnoski, Raphaël Barontini, Akea Brionne, Diedrick Brackens, Melissa Cody, Liz Collins, Cyrah Dardas, Carole Harris, Patrick Dean Hubbell, Josefina Concha E., Geoffrey Edwards, James Benjamin Franklin, Maren Hassinger, Margaret Hull, Basil Kincaid, Tiff Massey, Allie McGhee, Kamau Amu Patton, Esteban Ramón Pérez, Joey Quiñones, Jason REVOK, Eric-Paul Riege, Angélica Serech, Nirbhai (Nep) Singh Sidhu, with Nicholas Galanin, Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, and Ishmael Butler, Gary Tyler, Melissa Webb, Tyrrell Winston, Alisha B. Wormsley and Kite, Billie Zangewa, and Sarah Zapata.

lscgallery.com/exhibitions/warp-and-weft-technologies-within-textiles

1. Historic Detroit.org. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://historicdetroit.org/architects/donaldson-and-meier. 2. “Grace under Fire at the Shepherd.” Library Street Collective. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://lscgallery.com/exhibitions/grace-under-fire.

3. “Embracing Ai without Losing Ourselves.” Founding Fuel, March 17, 2025. https://foundingfuel.com/article/embracing-ai-without-losing-ourselves/.

4. “Warp and Weft: Technologies within Textiles at the Shepherd.” Library Street Collective. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://lscgallery.com/exhibitions/warp-and-weft-technologies-within-textiles. 5. “Technology Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technology.