Oliver Shaw

July 31, 2023

When Lizzie Borden made Working Girls, she wasn’t intending to directly comment on her own experience. Instead, like any filmmaker with true heart, she was telling a story she felt needed to be told. I’m a huge fan of everything she’s done before and since, but as I told Lizzie (as you are about to read), Working Girls is the standout.

In addition to a new restoration by the Anthology Film Archives released in 2021 by The Criterion Collection, she recently published her first book. Whorephobia: Strippers on Art, Work, and Life is a fascinating and powerfully informative read that is ultimately a sort of spiritual companion piece to the film.

A feminist icon and trailblazer of American independent cinema, Lizzie was kind enough to call me from her home in Los Angeles earlier this month. We spoke about everything from her early filmmaking days to Harvey Weinstein, “whorephobia” and pre-Giuliani New York City.

***

OLIVER SHAW: Alright, so first of all, thank you for talking with me today. I am really excited to be writing about this film and just ecstatic to have the opportunity to talk with you.

LIZZIE BORDEN: Thank you!

OLIVER: I only saw this film a couple years ago. I saw the restoration at the Austin Film Society and I remember immediately feeling like it was one of those films that made me forget everything I knew about cinema. I had really never seen anything like it. I had a similar reaction to Born in Flames but there was just something about Working Girls that really struck me. I’m not sure if it’s because I’m a man, I’m not sure exactly why, but I found myself thinking about it ever since seeing it and returning to it a lot.

One of the most interesting things to me is how enjoyable and entertaining and almost funny it is. I think it is a very funny film.

So, I would like to get into some of the themes and the issues that the film raises, but if it’s alright with you I’d like to start by just talking about some of the more formal elements.

LIZZIE: Yeah, well first of all, I’m glad that you found it funny, and also enjoyable because one of the challenges I had in making it was how do I make a film set in basically one set over a day not claustrophobic? And how do I make some of it funny so that it could be enjoyable? So, you’re saying that is very gratifying, thank you for it.

O: I’ve shown it to a couple friends since and it’s been met with the exact same response. Everybody was surprised by how funny it was.

Have you seen the film Tangerine by Sean Baker?

L: Oh, yes! I love it. He’s great.

O: I remember seeing an interview with him about that film—I think the main link between these two films, Working Girls and Tangerine, is the level of humor despite such a serious topic—and I remember Sean saying it was really just a reflection of the reality. That so many of these women, that’s how they talk about the work.

I think that may be missed with a lot of the audience, that they may see it as a cinematic decision to make it feel more like a movie. I’m wondering if that’s how you approached it or if it was more a reflection of the realism?

L: It’s a reflection of the realism, the reflection of it being based on the people who actually do it. In Working Girls, the characters were based on real people, sometimes a combination of real people. So it was a true observation of the working girls who were working girls in a very specific location. Some of the men were based on real clients or combinations of real clients.

In Tangerine they were actually working with themselves, taking on their own characters within the framework of cinema, and finding the humor in their own situations. Even though that frame was a cheating pimp.

I met Sean one time to introduce his new movie at the DGA [Directors Guild of America]. I’d never met him before in person and I absolutely loved him. Because I think we have the same appreciation for the real people behind the fictive frameworks of what we’re doing, but I think we approach it in the same way, which is that working is about labor. The idea of being a working girl is about earning a living, but it’s also the idea of friends. The idea of making it fun is how working women can get through a day.

With Working Girls it was a two part framework where Molly, the main character, is able to actually handle the daytime because she has camaraderie with the daytime girls—women, I should say—whereas at night, when she’s forced into working a double shift (because of the ruthless madam), she doesn’t have that camaraderie, which is what compels her at the end of the day to quit. Whether she stays or quits we don’t know. That’s the open question.

So yeah, there are similarities in the creation of fictive characters. And in Tangerine, yes, the two women were playing themselves essentially but I can see how you would see a similarity. Also the restrictive period of time.

O: Yeah, they’re both told in one day I’m pretty sure.

L: Yeah, yeah, exactly. And Working Girls was very stylized. That’s the one thing—I’m always surprised when people say it’s a documentary.

O: I know!

L: Tangerine was very stylized as well. There’s a story set in it, and Working Girls is a story. And the stylization is set from the beginning.

In the daytime, there’s always a dolly bringing in the clients. The only time there’s any overhead shots is upstairs with the clients themselves, where there are ellipses in time and any kind of music whatsoever. The score of the rest of the film is sounds, which gives the feeling to the place.

And the color scheme changes from the day to the night very slowly, so there’s a different way of shooting which changes from the day to the night and is bisected by Molly going out in the middle of the day to buy condoms, which is absolutely a funny scene.

O: Yeah!

L: That’s a way to kind of allow the audience to breathe in the middle of the day, and get some air, which is technically what Molly is doing.

She is breathing. She probably is wondering “Well, what am I doing there? Why am I going back there? Do I have to go back there?” She’s a good girl who wants to go home. She wants to be with her family. These are families living their lives. She doesn’t want to go back, but feels obligated to.

She’s a photographer, so she’s observant and it is shot by a different DP. Judy Irola, who’s an exquisite DP had another job. So Joey Forsyte, who’s also amazing, shot the scenes in the park in a more documentary way.

O: Oh wow.

L: It was two different DPs, so it was stylized for a purpose. And the shots in the brothel were stylized way before we were talking about “the gaze.” You know, we weren’t thinking about that. But I was very aware of having female DPs, shooting from angles where it wasn’t literally at angles where women would see ourselves, but certainly no shots that would be of the crotch, shots that would be titillating to an audience wanting to get off. It was the opposite of that. It was certainly not erotic in any way, I hoped.

O: No, definitely. How much of that was planned going into the shoot and how much of that stylization evolved throughout the process?

L: Oh it was all planned. I had a friend, who was a sculptor actually more than a set decorator. So he built the set based on the exact floor plan of the brothel that I was modeling it after.

I had a lot of rehearsal time with the actors, and with Judy Irola and we had one wild wall, the wall that the drinks were on came out. We didn’t have a dolly yet, but we were able to preview some of the moves, and the daytime women in particular were able to get used to working with each other.

It was hard to cast some of the men. The men who were easiest to work with weren’t exactly actors. Well some were. Fantasy Fred was from the theater group, Mabou Mines, and he was a lot of fun, as was Ricky Leacock, who played the guy who liked S&M…

O: Oh sure, yeah yeah.

L: He was D. A. Pennebaker’s partner in developing that camera you could put on your shoulder which also did sound.

O: Oh wow.

L: He was looking forward to being in this film, naked! He had so much fun. He was easy to work with.

Some of the other men came in and it was as if they were coming into a brothel because it was so many women. And we did all the sex scenes first so that they wouldn’t not show up for the sex scene.

But the women got used to each other, so we could practice first. It was a luxury. But time is a luxury, you know, when you have time whereas money, and I think we did all that for a hundred thousand dollars.

I think that Sean had the same feeling working on his film, that he got to know his two actresses the same way. And you can build those characters.

I remember it didn’t work out with the original person we were going to have play Lucy, so she [Ellen McElduff] came on later, which was fine, because the others had developed a kind of camaraderie and she was the outsider.

So it was fine because there was a tension between her and the other day-women, as there was supposed to be. And she did not like to have any deviation from the script, whereas some of the others liked to improvise, especially Dawn, who loved to improvise, which drove the actress who played Lucy crazy, as it should have!

So some of the shots were planned out but some were things that were a surprise from Dawn, but there was enough flexibility that we could do that. But still, since we were in a very tight space, there was only so much that one could do. And eventually, as we went on, because we shot in sequence, we could punch holes in the walls.

It had to be very planned, but with enough freedom to allow the acting style of these actors who, mostly were theater actors or, not exactly non-actors but maybe first time actors. A couple were actual working girls who stepped up because I couldn’t find enough people to do the nudity.

It was hard to cast in some areas, so it was an interesting process. But it was a process.

So, yeah, it wasn’t spontaneous. I mean, I was trying to find enough areas where spontaneity could be there. And then I edited for a long time. I kept the brothel set up as I edited. And I remember I had a Steenbeck, a flatbed editing machine. It was pre-digital back then, but I kept it up until I was done so that if I needed shots to use in between for ellipses, I could get them until I was done. And then and only then did that brothel set come down.

O: And did you end up needing it for a lot of shots or was it just more to have?

L: No I used a lot, like a magazine Molly’s reading or a clock or…little shots that were to bridge shots. It was very convenient.

And then there’s a scene in the kitchen where Molly and Dawn are sitting on the counter trying to eat some fudge and then they can’t. I think that’s an additional shot. We needed that extra shot to bridge scenes.

It looks lit a little bit different to me. I see that. But it was necessary. I was so happy I kept the set up.

I just consider myself so fortunate on both Born in Flames and Working Girls. With Born in Flames I was editing forever, I mean that film took five years. And Ulrich Gregor from the Berlin Film Festival, his section of it, the Berlinale, saw the film in my loft on the editing machine and invited it to Berlin.

With Working Girls, somebody told someone from the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes that it existed and he saw it in a screening room, unfinished, and invited it to Cannes. So I thought I have to finish. It was the same year Spike showed She’s Gotta Have It.

I was just so lucky that somebody said something about it. And then I remember rushing to finish it. We rented maybe four Steenbecks, editing machines, into the loft. Four people worked on finishing it with all the tracks, and then we had a great mix with Dominick Tavella—it was lucky to get him, he’s famous now—and it was done.

But it was great having a loft like that, because that kind of space allowed us in New York, all of us who made movies back then during that incredible eighties time, to have the luxury of time and space. Because so many of us worked in our spaces. And I know some people still have big spaces and still work in them, which is great.

That community long ago disbanded, which is kind of sad. I don’t know where the film community is now. I’ve heard there’s a big one in Detroit. Or different parts of New York. I’m not sure where.

O: Yeah, I mean, I’m in Detroit so I’m definitely trying to get more into the film scene here and just have loved what I’ve seen already.

L: Detroit is amazing. Detroit is…yeah, I think if twenty years ago I had contemporary ideas that I could do for less than $500,000 and I knew how to digitally edit, and I knew a few people, I would probably live in Detroit.

From what I’ve seen the couple of times I’ve visited, like around the art museum and then a few other places, wow—it’s phenomenal!

The energy there and the abilities to find spaces for less and find communities of people the way that we were able to work back then. Even though I think some of us like Bette Gordon and Vivienne Dick felt more political than other people.

Everyone I knew shared resources. One of the guys in Working Girls, Richard Davidson, was in Bette Gordon’s film, Variety. Nan Goldin, the still photographer for Working Girls was also in Bette’s film. Christine Le Goff, my AD, worked with Yvonne Rainer and Sheila McLaughlin (She Must Be Seeing Things).

Everybody did help each other in whatever way possible. I had an old Lincoln Continental which I parked illegally with a fake film permit in front of my loft, which everyone used! And everyone used my Steenbeck when they could, mostly during Born in Flames because I wasn’t using it all the time.

But I think that kind of film scene does go on in Detroit. And everyone knows how to edit digitally, so it can be more of a community. It all depends on housing, where housing is less expensive. And, you can get the other aspects of it.

The other thing about it was yes, with Working Girls I did build a set inside my loft. In Born in Flames, you could just walk outside and that was your set. In Detroit, you can walk outside and that’s your set.

There’s so much possibility in terms of the arts right now in Detroit. So yeah, I think if I were let’s say twenty years younger and had ideas that were present-day as opposed to period pieces, I would definitely want to be there! It’s very creative, and I think that’s what New York was, that kind of world where sexuality was. One didn’t judge it morally, you know. It was just there.

For instance, in New York in the 1980s, Cookie Mueller was a go-go dancer and Annie Sprinkle was doing art performances and women artists were performing nude, like Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke. You know, that kind of thing. It was downtown, a very open culture, so that’s why a certain kind of atmosphere existed for certain things to be made.

O: How do you think it’s changed?

L: Oh, you know, gentrification. Over gentrification. Rudy Giuliani destroying Times Square. Do you know the writer Kathy Acker?

O: I know the name. I’m sure I’ve—

L: Okay, well she wrote these very radical, edgy novels and did live sex shows in Times Square even earlier, in the late seventies. That was the atmosphere back then. We occupied lofts when nobody wanted them, when they were just empty industrial spaces because industry was moving out of New York.

I don’t know that Working Girls could have happened if I didn’t have the space to build a set. It would have been too expensive. We were the first gentrifiers, but we didn’t consider ourselves evil because nobody wanted the spaces. My rent cost four hundred dollars. That whole space. People had apartments for seventy dollars back then.

What’s happened now is that same rent is what, eight thousand, ten thousand dollars? It’s like Disneyland. And, what happened with Giuliani, who is one of the most evil men in the world now!

O: Agreed. It’s insane!

L: He destroyed Times Square. He talked about “cleaning it up” and he took all the character out of it and made it a tourist destination. Now downtown, where we used to work, is a tourist destination. For tourists looking at art, there’s still galleries, but on weekends you can’t even walk around.

I was just there a few months ago, and you can’t move. The interesting thing is, it’s not even just like a Sephora and Michael Kors, it’s like Rodeo Drive. It’s every top of the line store you could imagine on those same blocks where there was nothing. Where there were bombed-out buildings there are now pocket parks.

And, yes, that’s good in some ways, but it’s horrible in other ways because we’ve driven everyone out, and there’s just no way that anyone can live there, let alone artists who need space. And that’s why Detroit has been very attractive.

There were so many talented women who were cinematographers, and they were there in New York. And I could afford them. I wanted to actually pay the actors what I could afford and I went to SAG, the Screen Actors Guild, and they read the script and they said “but this is pornography”.

I said “this isn’t pornography” and they said “but, if it’s pornography, we can’t deal with it”. I said “what do you mean?” I said “read it, it’s not pornography.” And they said “no no no, it’s pornography and you can do whatever you want with it. Pay your people whatever you want. We cannot deal with this.”

I said “will you please put that in writing.” And they did, because I could only pay actors like seventy five a day. That’s all I could afford. And that was another reason it was hard to find anyone who would work with me because, truthfully, I wanted to pay everyone as much as I could. But I didn’t want them coming after me afterwards to say “you didn’t obey the low-budget SAG contract.” I paid what I could.

And Dawn, for example, she wanted to be an actress and she had an agent. And the agent told her “yes, it’s fine. You can do this, this is not pornography.” And it was distributed by Miramax before they were the Miramax that Harvey Weinstein turned it into.

He and his brother had a little office on the west side and, look, Harvey at that point was throwing desks against walls, which was not unfamiliar to me because my father used to do that, but I never saw him coming onto women. He was flirting with a woman at the office, but he married her. That was Eve, his first wife. So that did not seem weird to me.

I did not see anything out of the ordinary with Harvey then, only later did I. Later I had issues with him, but not during Working Girls except for the way he made the poster and tried to sell it as a come-hither, sexy movie…if a man came to see it and thought it was an erotic film he would probably want the price of his ticket back.

O: I’ve seen you describe it as a “film with a lot of sex that isn’t sexy at all” and I love that. I definitely think you achieved that. It’s funny how we just become so desensitized to the nudity by the end of the film, especially with Molly. We don’t even think about it.

L: That’s great! That was the point in a way, that you don’t think about her as an erotic object.

O: Not at all.

L: She’s in her body. That’s just normal. She’s going through the tasks of her work as work. And there’s a huge amount of attention paid on cleanliness—the towel, the washing up and the condoms.

That’s so great that you said that, because yeah, the idea that a woman’s body has to be erotic, to me is just so fallacious. But, I’m so happy that you felt that way too, because I had hoped that men could potentially identify with these characters in some way. Well, that’s a question I have for you. Did you identify with them? How did you feel about the female characters?

O: I loved them. I think they’re all so different and all so fully-realized that in its own right it feels almost like a hang out movie or something. And by the end of the film I sort of felt like these are my friends and we all, collectively, can hate Lucy together.

L: That’s great!

O: It’s really fun. It’s always surprising when I tell somebody about this film and I end up using the word “fun”, but I’ve seen it multiple times and I enjoy it even more every time.

L: Oh I’m so thrilled! That’s such an extraordinary compliment.

I think I’ve been riffing off the same first questions, so, I apologize!

O: No worries—this has been great! Just to switch gears a bit, and this is particularly interesting to me as a writer, but I wanted to ask you about the shift in language to discuss the sex industry. It’s my understanding that when this film was released very few people even knew what a “sex worker” referred to, and now it’s the common acceptable term. What are your thoughts about the shift in the language used to discuss, well all different kinds of sex work, I guess, not just full service?

L: Well, the word “sex work” had already been coined when I made Working Girls, but I was not aware of that or who coined it until Working Girls was done. As it was making its rounds I met the woman who coined the word.

O: Oh wow!

L: Carol Leigh, who recently died, she had coined the word maybe in ’82 or ’83—”sex work” and “sex worker”. She lived in San Francisco and I had done a panel with her and Margo St. James, who was part of a group called COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics) and a few other women in San Francisco. And I met Tracy Quan in New York, of PONY (Prostitutes of New York).

That began my education meeting women who talked a lot about sex work and decriminalization. I hadn’t really studied the politics of sex work, although “working girl” was the term that Lucy used because she didn’t like, as nobody would like, the idea of “prostitute” or “whore”, or any of the words that were not pretty enough.

They’re all middle class girls, and it’s very, very, very white, it’s very, very middle class, right? But, for me because you asked the general question, my whole evolution from making Working Girls has been an odyssey that I sort of have come back around to over the years. I recently published a book called Whorephobia. Did you hear about it?

O: I did, yeah. I just started it but I’m very excited to get into it.

L: Oh yeah, it’s okay. Jump around in it. But what happened was that I was really interested in the idea of sex work. Sex workers have been, to me, the most valiant people in the world. And strippers.

Whorephobia is my coming out book in essence, because there were a lot of women who worked at this one place in the 20s on the East Side while I was making Born in Flames. All the cool girls worked in this place. And I needed money, so I worked there for a few months.

But for years and years I always said it was a friend because I didn’t want people to think “Oh my god, that’s a film by a person who worked there.” I wanted people to look at the film for its formal qualities and see it as a film and not just as some kind of oddity.

But I was more interested in strippers because I had such respect for strippers. We used to always go see Cookie Mueller dance/strip/go-go or whatever, at a bar downtown. Strippers were just so outward facing, whereas the brothel is so hidden. You ring the doorbell, you use a secret language to get in, there’s so much fear and shame attached to it, whereas stripping just seemed like so much fun. It had costumes and glitter and music.

So, through Cookie and through other strippers like that I was always very intrigued by that because it was always something that none of the women I met, nor myself, could have ever imagined doing. But then after Working Girls had been shown, I sort of lost touch with that whole world and I moved to LA.

But then what happened was around 2001 or ‘02 I met a woman, Jill Morley, who had a box of stories by strippers, herself included, maybe six or seven stories by herself and one by Cookie.

They wanted to make short films, a series, and then the series never happened so I said “could I have the stories? I want to maybe do an anthology.” I got a story by Kathy Acker and one by Chris Kraus, but it was so hard for me to find anything. I thought I would focus on New York and New Jersey but there just weren’t enough stories. And the internet hadn’t exploded so it was hard for me to find other stories and I thought I had to stick to stripping because every different sex industry is different. Full service sex work is different than stripping is different than camming is different than men doing it.

What happened was when the internet exploded there became a situation where there were blogs where I could then contact strippers who were writing stories or memoir pieces. But very often they didn’t answer because there was a lot of mistrust.

Then, on the West Coast, I met a writer/dancer/activist named Antonia Crane. She turned me on to a lot of women who were still in the field, stripping, writing. And it opened up my world and I met a lot of younger strippers who were also doing full service sex work. It really politicized me in a way I hadn’t been before. And it still took quite a few years, but it allowed me to gather more stories.

The book is called Whorephobia but at first I thought it was a word used by a civilian to discredit a woman who was a whore. That’s not necessarily how it works. Antonia called it a “whorearchy”.

For example, it’s a stripper thinking she’s better than a full service sex worker, or a cam girl thinking she’s higher than a full service sex worker, or a dom because she has less physical contact with a client—that’s the whorearchy. That kind of condemnation of anyone doing sex work is whorephobia.

So it happens internally and externally and goes way back to the idea of any woman who is a sex worker being seen in negative terms, even going way back to the idea of the virgin and the whore.

I have such respect for sex workers. During the pandemic, especially, I saw how incredible it was that they supported each other, did shows, all with the profits all going to one particular woman so she could pay her rent, or get food or something. Very very very generous community, much more so than other communities.

And now, seeing how they are working toward unionization, and have just unionized a couple of strip clubs and are now included in the actors’ union—they’re very activist. I admire them in so many ways. That’s why, in my preface in Whorephobia, I come out for the first time. Because I feel proud.

In some ways I feel like I don’t have the credibility because I just worked for a few months so long ago. And because as a white, middle-class artist, I had the ability to say “okay, I’ve had enough.” Because I went in with a tape recorder and knew from the first moment I was going to make a film. And then when I had enough it was like “Okay I’ve had enough, I can find other ways to make money.”

But I had that privilege, whereas other women working at that particular brothel didn’t. They had to keep working. I tried to put a couple of characters in Working Girls who didn’t have that privilege, for example, an older character who kept coming back.

But one of the things in the book, in the collection, are writers who talk about the incredible racism that still exists in strip clubs, then and now. The book is really for the sex workers, a platform for their voices.

And there are some interviews they do with each other, because I wanted to create that same sense of…you said this beautiful thing that you felt like you were hanging out with them. I wanted to create the feeling that they’re talking to each other, that it wasn’t just me asking them questions, that it was them asking each other questions that I would’ve never thought to ask them.

O: Well, I’m really excited to get further into it, and I’ve been loving it so far.

L: Thank you for reading it.

O: Oh of course.

L: The trajectory from Working Girls to Whorephobia is that the idea of sex work, the idea of labor, has been so interesting to me. Jobs as sex workers are not going away. And one does not have to feel shame about jobs as strippers.

What I saw over the years was that there was a lot more shame way back when. And now, because of the activism, I see that there can be a lot more pride in the idea of choosing sex work as a job.

WORKING GIRLS is now streaming on The Criterion Channel and Max. Physical copies available at Criterion.com.

Images:

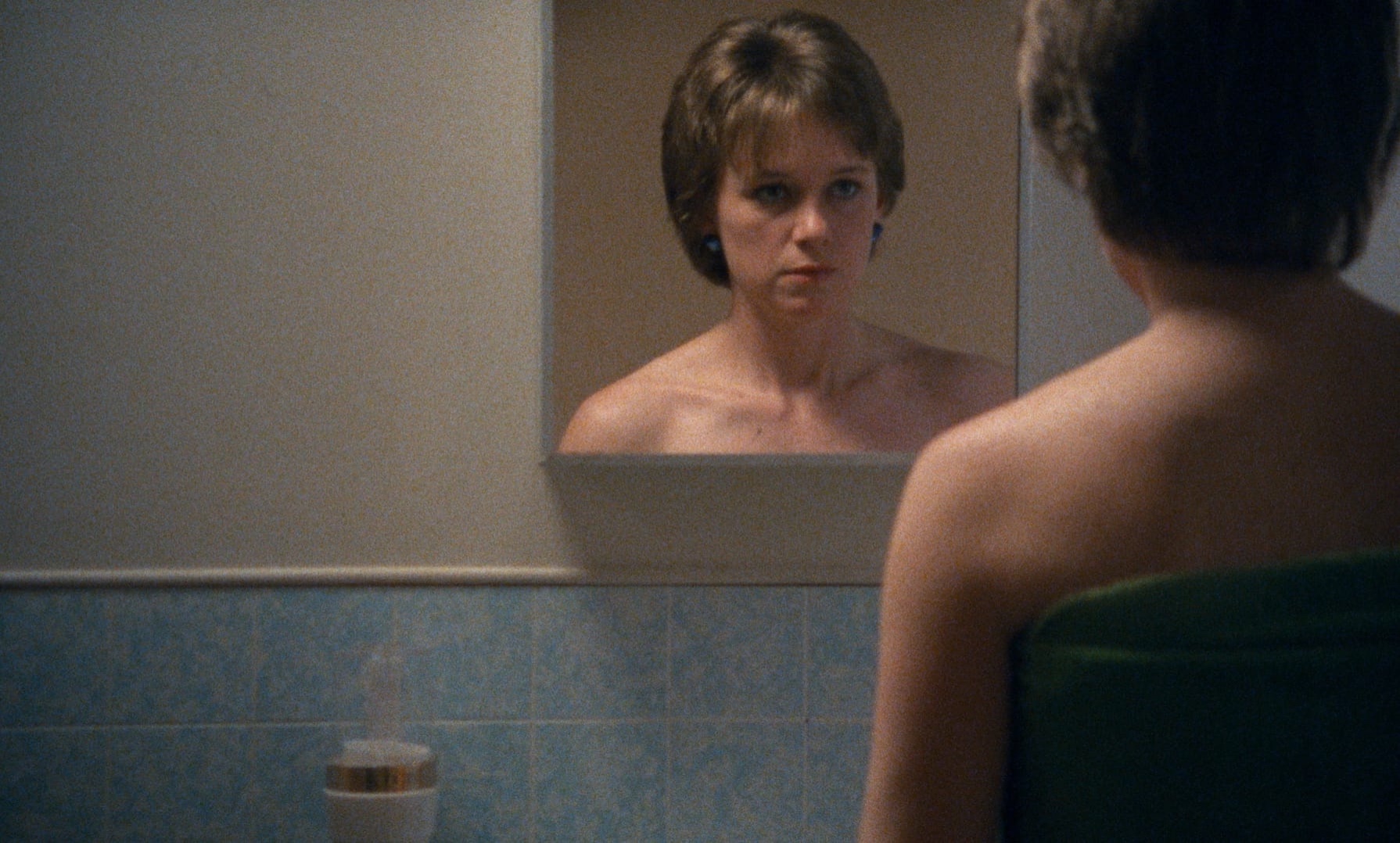

Borden, Lizzie. Working Girls. 1986; New York, NY: The Criterion Collection, 2021. 4K restoration.