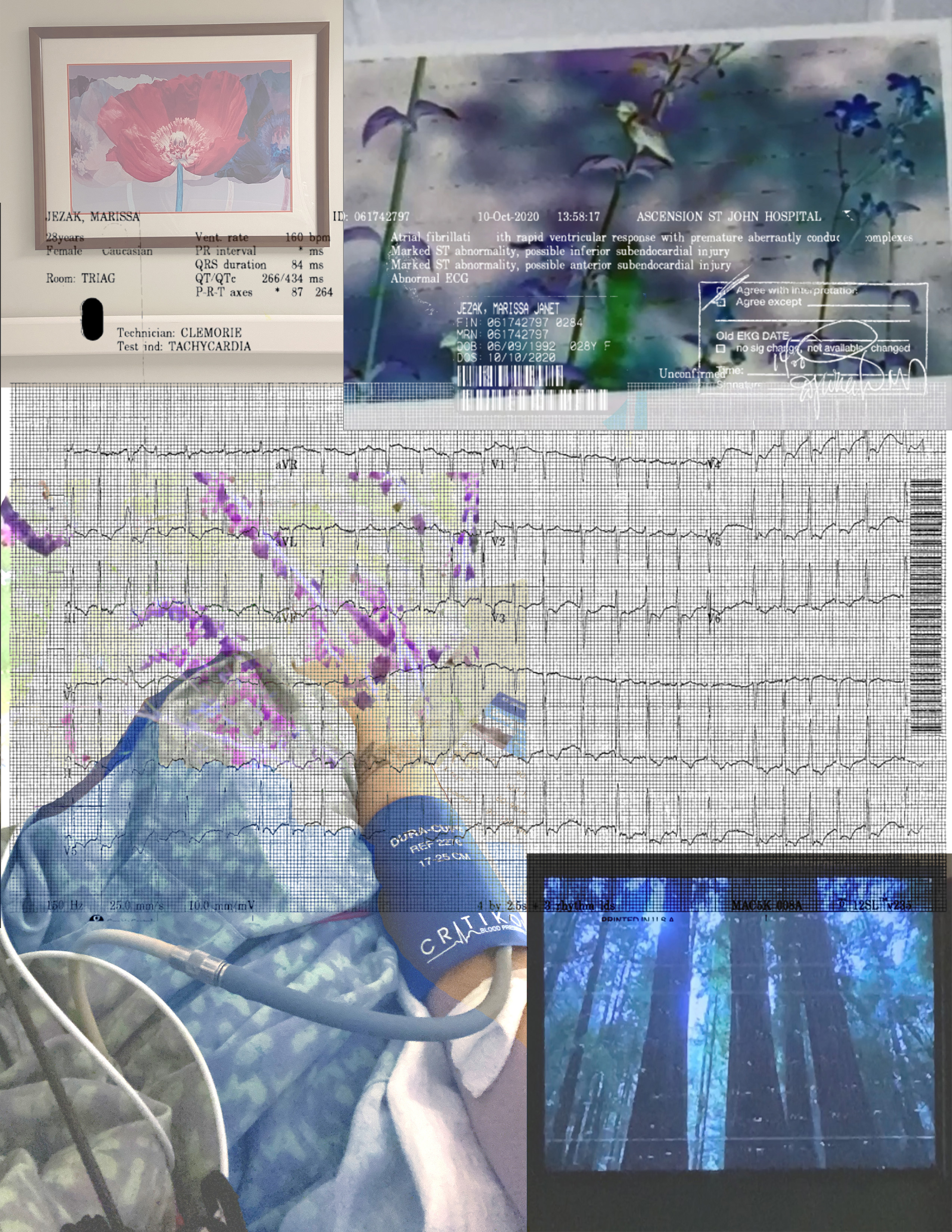

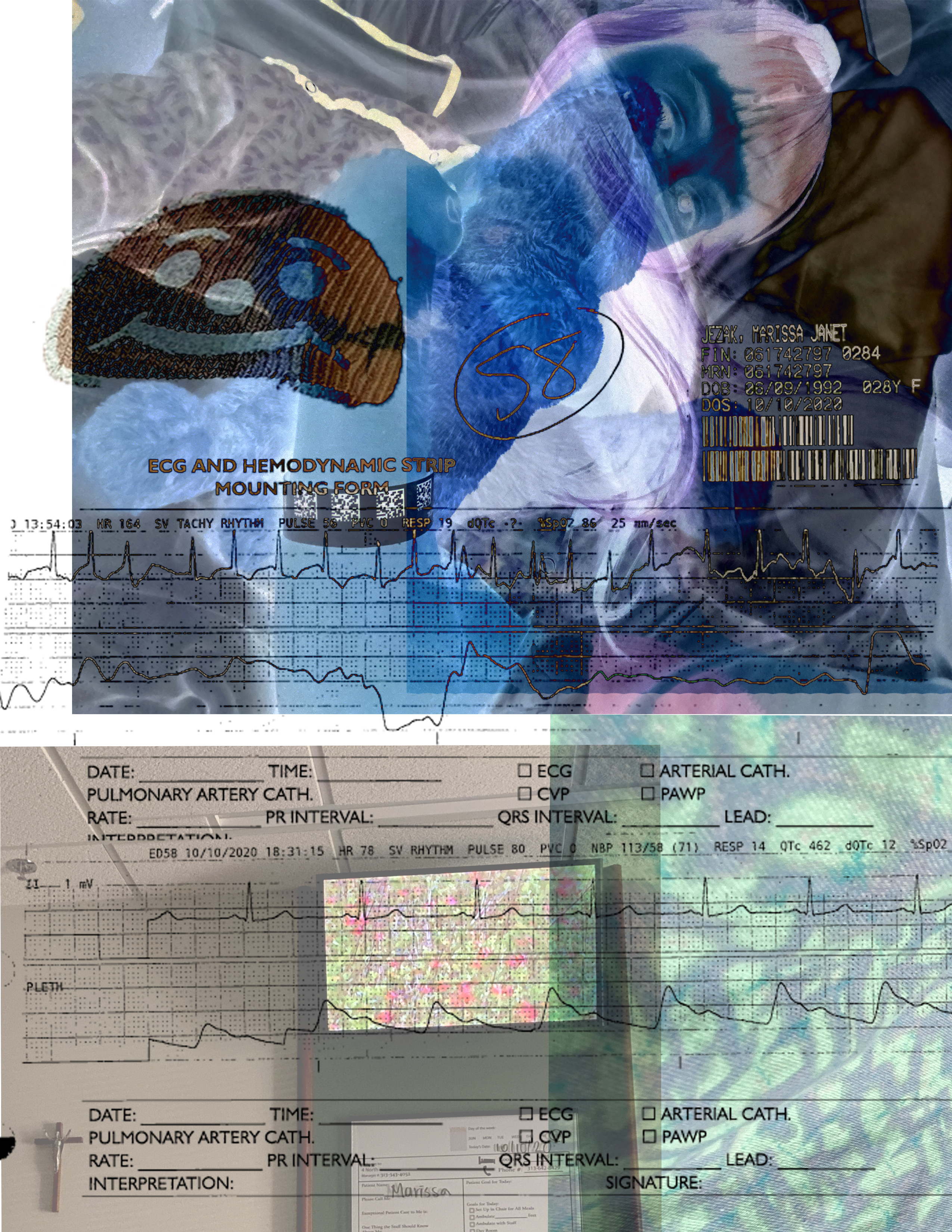

Marissa Jezak

October 25, 2021

calcium channel blocker

beta blocker

blood thinner

iv: saline

,magnesium

,potassium

burning through my veins…

feels like my blood is on fire

burning

volatile

vaporous

empty

cant lift my arms

cant do anything...

useless.

powerless.

trazodone

trapped

aching,

disintegrating bones

restless

wide awake, staring out the window

at pitch black nothing

looking for a way out

watching

static animals

on a screen

pacing

sitting on the bathroom floor

waiting for the sun to rise

to wait some more

To be able to understand healing, we first need to decode illness. Instead of seeing illness simply as the presence of disease, and health as its absence, illness can be defined collectively as:

1. a category inscribing a body

2. a physiological process that hinders lust for, and the vitality of life

3. a category constituted by bodily experience

4. a process through which identities are shaped1

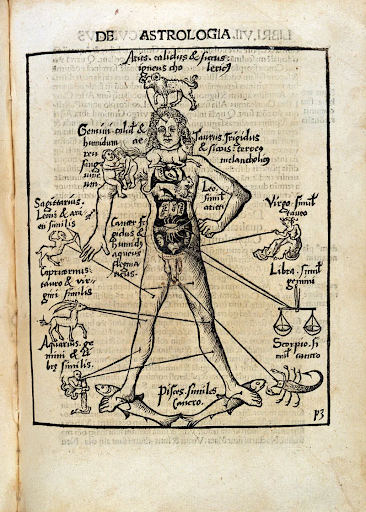

What transforms in the body when it becomes ill—not just physically, but its entire essence? In Shakespearian times, it was believed that we are each composed of four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile, that need to remain in balance in order for the body to be healthy. These humors were thought to have connections with the organs of the body; the four elements—earth, fire, air, and water; and the movements of the astrological realm. Depending on the positions of the different planets, and what you ate & drank, it could affect your humors and, subsequently, your whole being, body & soul.2

As healthcare has advanced with technology, it has also become more complex. To even begin navigating one’s health journey can be a feat in and of itself. Taking care of oneself requires resources: energy, reliable transportation, money, time, information. For people with ongoing health problems, sometimes they spend their whole lives seeking proper care, looking for answers, going back and forth from one specialist to another…trying to put together the pieces of the puzzle. Doctors don’t look at you as a whole being, they divide you into little parts that can be measured and analyzed—they diagnose and prescribe.

Since mainstream medicine has shifted to using pharmaceuticals as the primary treatment for practically everything, more people are rejecting Big Pharma, and instead are opting for homeopathic & alternative medicines, looking to ancient practices for solutions to their problems. In contrast to mainstream Western medicine, many holistic health practitioners believe in a strong relationship between spiritual, mental, and physical well-being, and incorporate this connectivity within their treatments. Approaching the subject of health from different philosophical viewpoints can help us expand our interpretation of what it means to be healthy and to heal.

In a utopia, we could live in perfect health all the time, but it ebbs and flows; sometimes we have balanced health, and sometimes we get sick. Illness is commonly defined as, “any somatic anomaly that can manifest to bother or make sick the affected person”.7 Concurrently, the impact illness has on the self can most accurately be referred to as suffering, which goes deep beyond the physiological...What role does illness play in the formation & altering of our identities? Checkups, tests, breakdowns, diagnoses, mis-diagnoses, experiments, hospitalizations, surgeries, traumas—all of these experiences impact our perceptions of ourselves. How we visualize our bodies and where they fall on a spectrum of sickness and health is inseparable from our overall identity and quality of life. How little or how much time we spend in doctor’s offices, hospitals, in pain/suffering, has a direct impact on who we are and in defining our life stories.

How does illness affect our perspective of reality? It distorts, clarifies—it makes things blurry, painful, too fast, too slow... Do we inhabit it? Ignore it? Tolerate it? Synchronize with it? We are so unaware of our physical & spiritual malleability until the moment something else takes control of us; when it takes over your body and shows you how fragile you really are.

INVALID

As often depicted in late nineteenth century painting and poetry, it used to be a mark of privilege for a woman to be chronically ill. In her essay, “Illness as Metaphor” Susan Sontag writes, “The Romantics invented invalidism as a pretext for leisure, and for dismissing bourgeois obligations in order to live only for ones art. It was a way of retiring from the world without having to take responsibility for the decision”.9 Indeed, for a woman to appear weak, emaciated, frail, and helpless was attractive by society’s standards—a symbol of virtuousness, purity, and spiritual salvation. Poet Coventry Patmore reflects, “She wearies with an ill unknown, / she sobs and seems to float, / A water-lily, all alone, / Within a lonely castle-moat”.

Moreover, many painters used their craft to exploit and romanticize the image of woman as an invalid—further popularizing the ideal of female fragility as angelic.10 In Louis Ridel’s Last Flowers we observe:

a young woman in the loose-fitting clothing of a terminal consumptive, leaning exhaustedly against her best friend’s comforting shoulder. The latter’s strong and healthy presence contrasts strikingly with the helpless ination of her companion. The healthy woman, it is clear, has taken her friend on a last outing to the lake along whose secluded banks the two had drifted so often in the past, picking flowers and exchanging the gentle confidences of close friends. Once again, as if to deny the course of time and the ravages of nature, they have gone back to haunt their favorite spots, but as was fated, destiny has overtaken them: Among the flowers plucked this time, among these dernieres fleurs, is the life of one of them-a woman who will fall into the waters of time as surely as the flowers in her hand must fall into the silent waters of the pond.11

In this way, the depiction of her illness fetishizes the female subject as a passive object. Her lack of control enables the viewer/other to inhabit a position of power / assume dominance, to enact nurturance or destruction, care or violence. The patient in the bed / model in the frame context possesses an intensely voyeuristic element, enhanced by the sick woman’s vulnerability—her stillness is objectifying.

Still, sickness is a luxury that most people cannot afford. Rather than resting when we don’t feel well, rather than healing, we tend to push our bodies beyond the limit—making them sicker. In our society, it is more important to make money than to take care of ourselves. Illness is no longer fetishized in the same way. Now, your physical ailments render you less attractive to society, less valuable…But our culture is not obsessed with wellness. Rather, it’s obsessed with the appearance of wellness—masking suffering. In her essay “Selfie-Care and the Uncommons”, Sarah Sharma explains, “Self-care is distinct from selfie-care [...] where women are instructed to recharge in order to re-enter currents of patriarchy/capitalism/white supremacy [...] The self taking care of itself has become a photo op [...] Selfie-care is a photo of a pair of feet floating in a pool of sudsy water [...] Selfie-care lists things one must do: Dance, Eat, Breathe, Hydrate, Touch a Tree, Send a Nice Email.”14

CARE+LACK

Undoubtedly, illness is exploited by capitalism & seen by the powerful as a liability. Many people hide their health problems in fear of being ostracized or discriminated against. Being mentally unstable, or having a body that’s inefficient are not desired qualities that employers look for in a worker. They don’t care if you’re healthy, they care if you can work. In her essay “Sick Woman Theory”, Johanna Hedva elaborates:

‘Sickness’ as we speak of it today is a capitalist construct, as is its perceived binary opposite, ‘wellness’. The ‘well’ person is the person well enough to go to work. The ‘sick’ person is the one who can’t. What is so destructive about conceiving of wellness as the default, as the standard mode of existence, is that it invents illness as temporary. When being sick is an abhorrence to the norm, it allows us to conceive of care and support in the same way.

Care, in this configuration, is only required sometimes. When sickness is temporary, care is not normal.17

In chronic illness especially, symptoms often fluctuate in severity. The inconsistency in health and (dis)ability to fully care for oneself on a daily basis makes it difficult to be self-sufficient, especially in a world where we are so isolated, and have virtually no concept of community-based care networks. Our culture is not equipped to take care of each other. Rather we are indoctrinated to practice an ethics of ‘every man for himself’. But this is not a sustainable vision... According to Hedva, “The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself. To take on the historically feminised and therefore invisible practice of nursing, nurturing, caring. To take seriously each other’s vulnerability and fragility and precarity, and to support it, honor it, empower it. To protect each other, to enact and practice community. A radical kinship, an interdependent sociality, a politics of care.”18

BODY/FLUX

There are a myriad of ways in which illness imposes limits on the body, and these bodily limits play a part in constituting our senses of self & identity. Illness closes off spaces, binding us to limited pathways. It devalues the body & self, designates it as being other, less-than, not capable of enough, unable to perform its duties as a capitalist tool. Perhaps maintaining optimism in the midst of an illness requires us to rethink the standards we use to differentiate “healthy” from “ill”. By shifting the borders around the concept of illness, we can rearrange our perspective of illness/health to be seen as less of a rigid binary, and more of a continuous fluid state, a fluctuating space that we define according to our individual needs. For example, instead of viewing illness as being unhealthy, it can be viewed as just being—without comparing oneself to a “normal”, “standard” or “idealized” body.19 When the material body destabilizes, the identity breaks down and reforms, redefining itself in its own terms—regardless of past identity or expectations imposed by others.20 In dealing with illness, often new identities can emerge that are more focused on caring for the self than pleasing others. In a case study of a woman with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (a complex chronic illness characterized by extreme fatigue that gets in the way of daily activities; including problems with sleep, mental cognition/concentration, pain, and dizziness), researchers observed how she adapted to the changes the illness had on her life:

By becoming aware of the multiple and

competing inscriptions on her ill body, she

has been sensitized to the discursive as well

as the material instability and unpredictability

of her body. Holding in tension the borders

of her illness, where her body re-forms,

she refuses to claim either illness or health; by

doing so, she claims both and neither at the

same time. Through her bodily activites,

she has been able to seek out a space—that

has been comforting during her transition—to

be whatever it is that she is at any given time.21

How changes in health affect identity is dependent on a number of specifics, and varies case by case. Receiving a diagnosis of a disease or disorder is not the same as accepting it. Many people live in denial of their ailments in an attempt at avoiding more suffering, refusing to adopt illness as a part of their identity, afraid of being perceived as weak. No one has time to be sick...When confronted with illness/violence, it’s often easier to just bury it— pretend it doesn’t exist, rather than deal with unpacking it & facing the issue head-on. Depending on the circumstances, a professional medical diagnosis can be very validating; it can also be shocking, and life-shaping—the key is to not let the illness completely suck you in... At the same time. it’s also vital that we alter the social structures shaping the division of labor and domestic care, which have a direct effect on our health—we need to have control over our bodies. We need to build up the support systems around us, thus allowing us to truly care for one another within our specific communities. Managing health/illness requires careful consideration of the context in which our bodies are functioning, and the demands being placed on us.

This is not my body—this is a machine that’s breaking down.

1 Isabel Dyck and Pamela Moss, Women, Body, Illness: Space and Identity in the Everyday Lives of Women with Chronic Illness (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 15.

2 Nelly Ekström, “Shakespeare and the Four Humours,” wellcomecollection.org, Wellcome Collection, December 11, 2016, Link..

3 Link.

4 Link.

5 Link.

6 Link.

7 Ken Flegel, MDCM Msc, “Take back the meaning of term illness”, ncbi.org, National Center for Biotechnology Information, July 13, 2010, Link..

9 Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978), 33.

10 Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-siecle Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 27.

11 Ibid, 25-26.

12 Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-siecle Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 26.

13 Health: Documents of Contemporary Art, Ed. Barbara Rodriguez Munoz (London/Cambridge: Whitechapel Gallery & the MIT Press, 2020), 147.

14 Link.

15 Link.

16 Link.

17 Ibid, 139.

18 Ibid, 140.

19 Isabel Dyck and Pamela Moss, Women, Body, Illness: Space and Identity in the Everyday Lives of Women with Chronic Illness (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 62.

20 Ibid, 132.

21 Ibid, 133.

(collages courtesy of the author)