Christiana Laine

November 23, 2020

The machines came to gnash their teeth

and bite at me

in the winter of 2017.

My sister with light blue blush

and the poison ivy

wound round her face in mourning

was eaten the day before

And our brother

smoke-blackened wedding chapel

dangling snaggle-toothed staircase

collided with ground

hardened mud and frosty dew

just the day before that.

Our cousin, glorious, jarring

last remaining

white ash

made wise by one hundred and twelve rings

Her arrow straight spine, it cracked the sidewalk

shook my bones, rattled the sparrows

May of the year before.

I stood tall, narrow, awkward

soaked through with spring and autumn rains

creaking in the seasonal winds

winds which rip powerlines from the sky

once striking fire to my neighbor’s garage

thirteen hours of flames

lapped by sea-breath

This sea-breath had danced through redwoods

made an acquaintance with coke-addled mountains

was entangled with smokestacks and flames of incinerators

weaving particulates into mammal lungs.

This was the winter before my manglement

Lives which passed through me

many layered and harshly synthesized

made peace (or didn’t)

with a menagerie in my walls

sinews of skin and boars’ hair in the plaster

shellac for the floors –

extracted from the sweat of insects

cattle hooves in the glue.

I had “good bones”

A shelter of substance

the height of the trees that built me

an anecdote for good old days

hard old days

hard days.

I did not buckle beneath the weight of the fatherless

nor the reckless

fearless

witless

ingenious

in love

enraged.

There was family and there was loneliness

rebellions inside my halls

“What are we going to do

about what’s outside these walls?”

And they did something

and there were awakenings

there were years of darkness

there was sadness with deep beautiful history

there were inventors and destroyers

forces of willing to make sense of the nature

a graveyard once, for a brief unmentioned period.

I wore hand painted lace and roses

heavenly honey amber stains

green glass tiles

viridian hues

My bones maintained while my organs failed me

my caretakers few and far-between

mulberry roots began to intervene

where I anchored in the clay

the glass of my eyes and various senses

splintered, misplaced

dissolved back into sand

spirits and wanderers need a place to sleep

a place to drink

a place to sit alone and dream

make a nest with paper bags

magazines

childrens’ chapter books

about a 4th grade teacher that is a vampire

and patinaed candelabras

a dry scrap of carpet

a wooden statue of a bird.

The machines collapsed me into myself

after my sister

and my brother before me

the height of the trees that built me

an anecdote for good old days.

- C.B.

In 2015 at the ripe age of 22, I bought what some would call an abandoned house. It’s been a common move as of late in Detroit, if one can scrounge up a few thousand bills.

“Never pay rent again, design your dream home, breathe new life into decay”.

It presented itself with a plywood “door” inscribed haphazardly in blood-red spray paint “For Sale - Best Offer”. This house shared its yard with the house of a good friend, so we climbed through a busted window one day and took a look inside. The curious thing about the word “abandoned” is that it implies emptiness, and what we encountered that day set the stage for a lesson I would never stop learning - a hundred and twelve-year-old house is anything but empty.

On that first day, in thin streams of sunlight that peered around edges of boarded windows, each careful step awoke dormant dust motes, the first signs of vibrant life. Actually, that was the second sign. The first was the long-held breath that exhaled from each room as we entered. And then came the objects, the toys and books, the blankets, the backpacks, the clocks, the pots, the cigarettes. The wooden parquet floor was intact, I saw sketched in it the scuffs of dances, dinners, fights, movings in and movings out.

I called the number at once and made an insanely low offer – less than I’d paid for my used station wagon. And because this house had been bought at auction by out of state developers who had never set foot on the street, soon to lose ownership back to the Land Bank, they accepted my offer on the spot. There were no keys to exchange, no door to unlock. It was suddenly “mine”.

Just like Detroit is not a blank slate of a city, an old home is not a blank slate of a house. I moved in amidst traces of wanderers past and present – those whom had found home in its belly after generations of “owners” had moved on. No, this place was not empty, nor was it forgotten. It revealed itself to me in layers. In literal layers of paint, wallpaper, and soot, and ephemeral layers of emotion and memory.

I would argue that the most historic buildings in a city are its old houses. In Detroit, the single-family homes sprawl as far as the eye can see (just don’t blink or they might be half-gone). When I think of their inhabitants, I picture the figures of Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals come to life, arriving sore and sweaty on the doorstep, dragging their boots across the threshold, washing themselves in the tub, kissing a child, a wife or husband, a dog, and smoking a cigar in the kitchen. These were the safe spaces for the bodies that brought Detroit its fortune, those whose children paid the price when that fortune one day turned south. I never succeeded much at researching the true former owners of the house, but I did not feel alone there, and it did not feel like a haunting. I lived without heat, without plumbing, on a mattress, by candlelight. Like a squatter with a piece of paper to prove I alone deserved to be there. It was like a cabin in the city. I had no business renovating a house, but I’d spent much of my life finding comfort in strange circumstances.

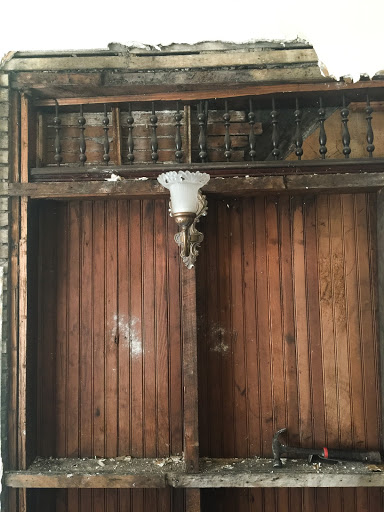

My partner at the time and I just chipped away at what we could with the little money that we had, lighting a fire in the tiny wood stove each morning, burning wood from a tree that had lived and died on the lot, older than the house itself. I had no master plan; just letting the house speak and laugh at me. One day I took a sledgehammer to some crumbling plaster and found behind it a finely crafted wooden accent wall. In another room I discovered a false fireplace, where white peeling paint revealed green glass subway tiles. I made bookshelves in the walls out of lathe, left exposed patches of yellowed wallpaper, removed a whole wall to open the kitchen to the dining room. I filled it with furniture threadbare and ancient enough to befriend it, hung curtains and quilts over imperfections.

I would sit on my porch sometimes and the walkers there almost always stop to say “hi” and make observations. On two occasions, I met former residents of the house. One of them in his 20’s, had lived there as a foster child. One of them a very old man with frustratingly little else to say. I would think of the sacred history of its place in space. The Elmore Woods turned Islandview neighborhood. Its proximity to Eastern Market, Mayors Coleman Young and Kwame Kilpatrick’s former homes, the ribbon farms of Poletown, Belle Isle; and from my front porch - a straight shot view down Vernor Hwy. to Downtown Detroit.

Much of my personal artistic work since coming to Detroit has centered around the interconnectedness between all things and every element’s necessary part in the greater unwinding and rewinding of life. I think being specifically here and knitting myself into its fabric has taught me a great deal about that.

Two years later, some “good Samaritans” came for the neighborhood. Briefcases of money and blueprints and talks of improvement and beautification. I had just put a new roof on a house with half its windows and, by then, a wobbly main sewer line I’d installed myself. There was deep water damage, a hard lean to the north, lead paint, and termites. Squirrels and possums made their nests upstairs. I was beginning to feel I couldn’t handle the depth of the house’s demand for attention. The buyouts happened quickly, many neighbors were happy to sell and eventually, I chose to as well.

I watched that house come down a few months later. The blight task force makes quick work. In less than 10 minutes, this home to me, this home to I don’t know how many, was a pile of rubble and one perfectly preserved door, standing straight up, white like surrender. Sometimes I feel guilty for making this choice, for being the one with the power to make the choice in the first place. I find small comfort in knowing I did my best to honor its beauty, its spirit and its life before it had to go.