Ashley Cook

February 19, 2024

Every second that time passes marks the edge of an ongoing era where modern societies barrel forward into the future without looking back. Over the years, our growing obsession with technological advancement has forged a widely-held belief in the supremacy of the human race over everything else on the planet. This tenacious thirst for “progress” became concrete in the Manifesto of Futurism by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, written in 1909, that emphasizes man’s entitlement over women and modernism’s triumph over everything that is not modern. Above all else, this proclamation favors a future-focused dominance that is fueled by dynamism, speed, violence, and technology, laying the foundation for our endless quest to imagine and invent utopia.

Social theorists around the world acknowledge Detroit as a complex place that was once built as a “utopian vision of the future”1 and now exists as utopia’s perfect antithesis. The city’s time-line has followed the devolution of many cities depicted in science-fiction tales, giving rise to cyberpunk, a subgenre of science fiction that focuses on a future of artificial intelligence and cyborg forms living amongst humans in an Earth-based dystopian society. Tracing the stages of Detroit’s ascent followed by its downfall is a real-world study in the slow collapse of our blind faith in the industrial revolution found both in textbooks and storybooks. The broken-down landscape formed by the city’s unique history became a stage for its musical protagonists to redefine. The ruins of the post-industrial world were reanimated through an innovative use of technology and Detroit became the first self-aware, nonfiction embodiment of a cyberpunk landscape in the world.

Science fiction has often used the cityscape as a representation of Futurist aspiration, but in cyberpunk, the city is used to frame its flaws. Future noirs like Metropolis (1927) and Blade Runner (1982) were quintessentially dark, with skyscrapers climbing so high into the polluted sky that they block the sunlight entirely. The buildings of these vertical cities were designed to contain everything necessary to live in order to limit the need to leave. The wealthy residents lived at the top as far away from the poverty and lawlessness on the ground as possible.2 Detroit’s Renaissance Center, built in 1973, actually attempted to realize this fantasy to build an entire city inside a single structure as an alternative to confronting the challenges of the streets.3 A similar structure was built in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1975 called Ponte City Apartments,4 but neither of these constructions succeeded in ameliorating social strife.

Fantasy as a pop-cultural theme has proven to be useful in the persuasion of ideas. It may actually be one of the most influential tools that a culture has to subconsciously inspire consent and participation amongst its citizens, functioning in tandem to texts like The Futurist Manifesto. As early as the 2nd century CE, themes of space travel, interplanetary warfare, and artificial life entered the minds of readers through the first noted science fiction tale, A True Story by Lucian of Samosata. Since then, the literary genre of science fiction has continuously re-introduced hopeful visions of a world enriched by technological advancement and interplanetary colonization. But as science-fiction and reality began to more consistently overlap through references to Earth-based societies, challenges of the futurist agenda became more present in the books. Real-life circumstances provoked a shift in the genre and authors began to embrace gloom as a setting for their characters. The hopeful drive to build cities into the clouds had suddenly joined the shadows of exploitation and pollution on the same page, and the bite of reality became palpable even in fiction.

The exchange of science-fiction and real-life events had become so tightly woven that it can sometimes be difficult to determine the precise source of influences on our world building efforts. Graphic design, architecture, and art played with sci-fi literature in a game of back and forth as they sought to realize an impossible future that was always just over the horizon. Consciously editing the visual elements of reality was an action that had the capacity to foster a future-focused viewpoint and lifestyle, and the music became its soundtrack. In the 1950’s Sun Ra started to actively contribute to the fascination with interplanetary travel and hope for a technological future through the use of synthesizers, lyrics about the cosmos, and science-fiction themed outfits and headdresses. He and his Arkestra significantly influenced the future of music as an element of Afrofuturism. They worked in tandem with Black science fiction stories by writers like Samuel R. Delaney, who envisioned the African Diaspora through the lens of technoculture and penned an alternative future that placed Black characters in the center of the stage. Delaney’s novel Nova is considered one of the first stories of intergalactic space travel that included depictions of cyborgs co-existing with humans, aliens, and technological life.5 Written in 1968, the story’s human/machine hybrids were simulated in real life through the musical performances of groups like Parliament Funkadelic (based between Detroit and New Jersey), which formed that same year.

Eurocentric approaches to electronic music of the 1970s also celebrated invention and looked to the future with delight. The clean, precise aesthetics of Kraftwerk mimicked German engineering and Giorgio Moroder drew influence from Italian Futurism, reiterating a submission to posthuman mechanics through repetitive beats and lyrics. But while these artists continued to feed the world an idea that technology would be the agent to bring us into a new time of prosperity–freeing us from the limits of our organic condition, Detroit was simultaneously experiencing a societal collapse as a result of this very same ambition.

The city’s reputation as an industrial legend was of course founded in the birth of Fordism as a method to achieve mass production through the standardization of forms processed by machines and unskilled labor. The assembly line was invented to improve productivity in the automotive industry and was highly instrumental in Detroit becoming the fourth largest city in the U.S. with a population of over 1.8 million by 1950.

People were coming from all over the country to work for The Big Three and earn a living wage. But just at the height of this prosperity, the auto makers introduced new technology that replaced the jobs of many workers.6 The fuel crisis of the 1970s and new competition from foreign automakers caused even further instability, leading to multiple plant closures and a growing rate of unemployment in Detroit. The risks of relying on a single industry quickly became apparent as Detroit descended into a place of crime and deterioration almost overnight. Between 1970 and 1980, over 300,000 residents fled to the suburbs to escape the volatility. This mass exodus wiped out the tax base and resulted in the closure of cultural institutions and essential social programs as well.7 In just 30 years, Detroit both earned a status as the ideal city of the Modernist Future, and became the case-study for its demise.

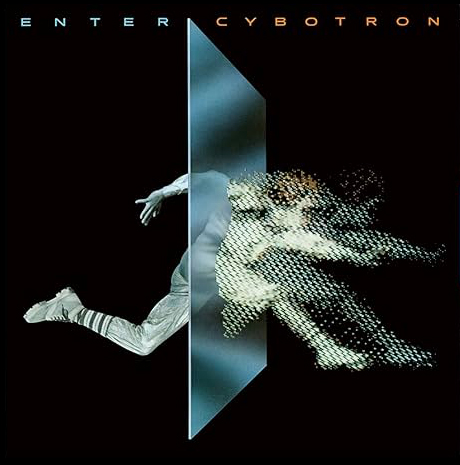

At this point, Futurism’s expeditious drive towards progress has left so many behind. In 1980, as a sequel to his 1970 book Future Shock, writer and businessman Alvin Toffler published The Third Wave. In this book, he reflects on the transition of the modern world from the Industrial Age to the Information Age. He also takes into account where we have been as a technological society, where we currently are as a Post-Fordist, Postmodernist Society, and where we are headed—with an emphasis on the central role that information plays in the spread of globalization, decentralization, and diversity. Toffler invented the term “Techno Rebel” to describe forward-thinking people who actively set out to provide solutions for an alternative future, where the “people reclaimed technology for the benefit of the community”8 as opposed to the benefit of the corporate industries. Juan Atkins—one of Detroit techno’s first wave of producers, notes having been influenced by the writing of Toffler. At an early age, Atkins took Future Studies, a high school class in Belleville, where he met and collaborated with Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May to form the Belleville Three. Soon after, they introduced Eddie Fowlkes as a fourth member of the group. Atkins later used the term "techno" to describe the music of Cybotron, his collaboration with Richard Davis. Their album Enter, released in 1983 (later retitled Clear), is considered to be the first Detroit techno record, defining the Detroit sound with characteristics like 4/4 beats, critically futuristic lyrics and modulated industrial noises like alarms or sirens to produce a post-human type of music appropriate to a dystopian environment.9

Coming up alongside Octavia Butler’s short story Speech Sounds, also published in 1983, both Detroit techno and Black science fiction began a new journey to explore the modes of identity that spawned from a post-apocalyptic landscape, without necessarily striving for a resolution.

This new approach to recognizing dystopia as a more realistic vision of the future appeared again in the novel Neuromancer by William Gibson, published in 1984. The story is set on planet Earth between an urban sprawl called The Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis (BAMA), a city called Chiba and its neighboring underworld, Night City. Neurmancer solidified the theme of cyberpunk through detailed descriptions of entities like artificial intelligence, technological integration into the human form, virtual reality, cyberspace, and the fragmentation of identity caused by a capitalist system’s dehumanizing and profit-driven practices.10 This novel was considered as the official introduction of cyberpunk into the genre of Science Fiction, and paved the way for infinite subsequent explorations.

With minimal government oversight, a shrinking middle class, abandoned buildings, crumbling infrastructure, drug use, and criminal activity running rampant, Detroiters found their urban circumstance represented in fictional places like the underworld of Night City. But while the situation was dire in so many ways, there was also a new type of autonomy and innovation occurring that could only come about in such a wild place. Around the time that techno emerged, figures like The Electrifying Mojo embraced diversity through dynamic radio shows and DJ sets that featured music from all different backgrounds, inspiring Detroit’s late night culture to become increasingly mixed in a social, racial, and sexual way. Tunes by Detroit techno producers were played amongst hits by Prince, The B-52’s, Kraftwerk and Giorgio Moroder.11 With clubs open till 2am and after-hours parties going til’ dawn, there was plenty of time for the DJs to mix and match genres and explore the intricacies of music from different cultures. Detroit’s mayor at the time, Coleman Young, who held office from 1974 to 1994, was himself a fan of late-night partying and gambling, so he was a proponent of the city’s busy night life.12 This creative renaissance—powered by adapted drum-machines, gave birth to the raves in abandoned warehouses throughout the city. Hundreds of people at a time were drawn to participate in a collective experience of decentralization similar to the concept of cyberspace described in William Gibson’s Neuromancer. The focus of the event was not on one single source or mediator, but instead, spread out between various points, from the performers to the dancers to the lights projected onto the architecture.

The rave culture defined by collective participation proliferated to incorporate looks that were drawn directly from the genre of cyberpunk, exploring human/machine hybrid forms and in some cases human/animal hybrid forms. It is worth noting however, that unlike the fantastic wardrobes of techno bands like Kraftwerk—who were presenting a fiction-esque/performative approach that was all-encompassing, many Detroit techno producers themselves embraced everyday streetwear as an appropriate outfit to represent music of the future. In a way they were saying, “we are already in the future”. The radical qualities inherent in the techno and rave scenes of Detroit were founded in its inclusion and diversity. Compared to movements like punk, which became recognizable as a subculture through the particularly crass fashion trends, specific hairstyles, and lifestyles, the culture surrounding techno music in Detroit was unpredictable and therefore could not be commodified or controlled. ”The music, and the affect around which it circulates, is—or at least was—meant to “speak” for itself, precisely to the extent that part of what it expressed was the demise of coherent identity in the fading of the modern project”.13

Detroit techno came to be in high demand all over the world. Top producers even performed at raves in East Berlin just after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.14 In the year 2000, Isamu Noguchi’s Hart Plaza was selected to host the Detroit Electronic Music Festival right off the river. In the first three years, this single event drew around 1.5 million people from all over the world, which was a higher number than the entire recorded population of the city at that time.15 Detroit’s steady decline of population and industry continued into the new century, while Detroit techno represented a lifestyle that embraced dystopia as a common place of the future. This philosophy is one that provides an alternative solution for millions of people all around the world who were left behind by the technological progress and other achievements of modernism.

Dystopian themes in music, art and literature continue to be fashionable topics in academic circles as subjects of a postmodernist investigation that does not ignore the challenges happening on Earth, but instead, frames them and zooms in. The genres of cyberpunk and Detroit techno demonstrated an individual ability to present radically realistic views of the human experience in the age of technology and information allowed them to sustain a critical relevance nearly decades after their entrance into the Futurist conversation. The cyberpunk literary genre and Detroit techno musical genre both consciously and subconsciously worked in tandem to form a fiction/non-fiction hybrid that is a direct experience of radical acceptance, in which the blind drive towards an impossible utopian future is abandoned in exchange for a clear view.

1. Gary Kun Chan, “(Re)Imagined Futures of Detroit: Dystopian and Utopian Views of the Motor City’s Future.” Intersect - Standford University, 2011. Link.

2. “Neuromancer: The Origin of Cyberpunk | a Horrifying Dystopia.” YouTube, July 14, 2023. Link.

3. “Anatomy of Detroit’s Decline.” The New York Times, December 8, 2013. Link.

4. “Neuromancer: The Origin of Cyberpunk | a Horrifying Dystopia.” YouTube, July 14, 2023. Link.

5. “Science Fiction Cities: How Our Future Visions Influence the Cities We Build.” New Atlas, July 30, 2018. Link.

6. Leonie Hagen, “An Exclusive Renaissance .” Runner Magazine, no. 1 (April 26, 2021). Link.

7. Kaid Benfield, “Apartheid and Its Aftermath, in the Story of One Very Tall Apartment Building .” Smart Cities Dive, 2017. Link.

8. “Alvin Toffler’s Description of Techno-Rebels from the 1980 Book The Third Wave.” Gist. Accessed February 13, 2024. Link.

9. “Detroit Techno Timeline.” The Music Origins Project, October 12, 2020. Link.

10. YouTube, “Neuromancer: The Origin of Cyberpunk”

11. The Music Origins Project, “Detroit Techno Timeline”

12. Ashley Zlatopolsky, “The Roots of Techno: Detroit’s Club Scene 1973–1985.” Red Bull Music Academy Daily, July 31, 2014. Link.

13. Richard Pope, “Hooked on an Affect: Detroit Techno and Dystopian Digital Culture.” Ryerson University, 2011. Link.

14. 4 Lydia Beardmore, “How Techno Became the Beating Heart of Berlin.” Medium, March 11, 2022. Link.

15. “Detroit, MI Population by Year - 2023 Statistics, Facts & Trends.” Neilsberg. Accessed February 13, 2024. Link.

*Thank you to Crystal Gause, Marissa Jezak and Joseph Schimmel for editorial support